Transformations

- Musical Analysis Section

- Audio Recordings Section

- Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

- Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

- Carlisle - Gerald Finzi: A performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and

- Denning - A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

- Rogers - A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas Hardy

- Bray - An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

- John Keston - Two Gentlemen from Wessex, The Relationship of Thomas Hardy's Poetry to Gerald Finzi's Music

Poet: Thomas Hardy

Date of poem: (after 1913 - the exact date is not known)

Publication date: In the collection: Moments of Vision (1917)

Publisher: Macmillan Publishing Company

Collection: Moments of Vision and Miscellaneous Verses (1917)

History of Poem: Richard Little Purdy writes as to the title: "MS. [manuscript] shows 'In a Churchyard' as an earlier title (or perhaps sub-title)."

(Purdy, 198)

Martin Seymour-Smith records in his Thomas Hardy biography the following account early in Hardy's life: "At this period too, as he described in the Life, he was attracted to several girls, who he adored at a distance in the idealistic manner of adolescents. he was, he says, 'over a week getting over' an attachment to a girl he saw on horseback; he told 'other boys in confidence' about her, and they 'watched for her on his behalf'. This was followed by an attachment even deeper, which occasioned no fewer than four poems ('Transformations'; 'The Passer-By'; 'Louie'; 'To Louisa in the Lane'), as well as the mention of her Christian name in the Life."

(Seymour-Smith, 30-1)

Martin Seymour-Smith goes on to describe Louisa Harding and offers a possible time-line as to when Hardy may have composed the poem:

"Louisa Harding was one of the twelve children of a well-to-do farmer of Stinsford, for who his father had done some building word, and Tom seems always to have worshipped her from afar. He had perhaps just then lost interest in a girl from Windsor who annoyed him by 'taking no interest in Herne the Hunter' despite her reading of Ainsworth's Windsor Castle, and had got over being despised by a gamekeeper's red-haired daughter called Elizabeth Browne; but his interest in Louisa 'went deeper'. After her death in 1913, at the age of seventy-two, he used often to ponder over her (unmarked) grave in Stinsford churchyard. As a result of one such visit there he wrote 'Transformations'." (Seymour-Smith, 31) |

Kenneth Marsden suggests: "The original inspiration for this [poem] could easily have come from Fitzgerald's 'Rubaiyat', but Hardy's profession as church restorer and his predilection for graveyards could keep the whimsy in mind, or even suggest it to him. Why it should interest him as a speculation is obvious enough."

(Marsden, 68-9)

Poem

| 1 | PORTION of this yew | a |

| 2 | Is a man my grandsire knew, | a |

| 3 | Bosomed here at its foot: | b |

| 4 | This branch may be his wife, | c |

| 5 | A ruddy human life | c |

| 6 | Now turned to a green shoot. | b |

| 7 | These grasses must be made | d |

| 8 | Of her who often prayed, | d |

| 9 | Last century, for repose; | e |

| 10 | And the fair girl long ago | f |

| 11 | Whom I often tried to know | f |

| 12 | May be entering this rose. | e |

| 13 | So, they are not underground, | g |

| 14 | But as nerves and veins abound | g |

| 15 | In the growths of upper air, | h |

| 16 | And they feel the sun and rain, | i |

| 17 | And the energy again | i |

| 18 | That made them what they were! | j |

(Hardy, 472) |

||

Content/Meaning of the Poem:

1st stanza: A part of this evergreen shrub/tree is a man my grandfather once knew, joined in the roots: this branch of the shrub may be his wife, who now is new growth.

2nd stanza: The grave of a woman who frequently prayed for rest and peace is now the grass above her grave; and a girl whom I loved from afar may be mingled in this rose bush.

3rd stanza: So these dead are not buried but live on above the soil, where they can feel the sun and the rain, and absorb the energy and change the air that kept them alive before when they were in human form.

For additional comments as to possible meaning of the text please refer to: Content - Van der Watt.

Speaker: Thomas Hardy

Setting: "Hardy identified the scene as Stinsford Churchyard." (Purdy, 198)

Purpose: Poses the question that life may not end when we take our last breath.

Idea or theme: Re-incarnation, re-birth, transference.

Style: "The poem has a pastoral, lyrical style with a religious-philosophical under current or intention." (Van der Watt, 144)

Form: "The poem consists of three sestets with lines of Uneven length. The rhyme scheme is a mixture of paired and rounded rhyme: aabccb ddeffe gghiih. The metre is mainly trochaic and iambic." (Van der Watt, 144)

Synthesis: Mark Carlisle writes in his dissertation with regards to Transformations: "The poem shows us a glimpse of some of Hardy's deepest spiritual convictions. As an agnostic and self-proclaimed realist, he could not believe in a biblical afterlife, but instead found reassurance in the belief that mankind lives on in a physical sense by becoming food for the life around him. This is evident from the fact that Hardy owned and read T. H. Huxley's essay, "The Physical Basis for Life," which states, "There is a sort of continuance of life after death in the change of the vital animal principle, where the body feeds the tree or the flower that grows from the mound." (Ransom, 187) This concept of immortality today might seem morbid to staunch Christians, but for Hardy it was a concept in which he found much comfort." (Carlisle, 163-4)

Published comments about the poem: F. B. Pinion writes: "In [this] poem we have a rationalist view of physical 'immortality'. It is found in Emily Bronte's poetry and in the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam:"

"I sometimes think that never blows so red The Rose as where some buried Caesar bled; That every Hyacinth the Garden wears Dropt in its Lap from some once lovely Head." |

F. B. Pinion also suggests that one consider Hardy's poem Voices from Things Growing in a Churchyard when analyzing Transformations. (Pinion, 136)

Dennis Taylor places Hardy's Transformations in a group of poems Hardy wrote after 1913 of which Taylor calls: "mature ghosts." "Hardy's mature ghosts are grotesque because they are here and not here; they are immortal and they are only decaying bits of nature; they are the living past that has ceased to exist - and yet they are part of us. Present reality, wrought into visionary material by the ghosts and the fervid ghost-seer, threatens to 'return' in the form of the grotesque." (Taylor, 107-8)

Kenneth Marsden writes: "Readers of Yeats are familiar with the fact that implausible beliefs can provide an excellent mental framework for poetry, and poems by Hardy also show this. (Both poets, to some extent, regarded these beliefs as poetically useful myths, and were not always prepared to assert them outside the poem.) Several show immortality achieved by a sort of vegetable metamorphosis or transmigration, e.g. 'Voices from Things Growing in a Churchyard', 'Shelley's Skylark' and 'Transformations'. All of them are fine poems, though the last is rather embarrassingly explicit." (Marsden, 68)

Tom Paulin writes in his Observations of Fact: . . . "Voices from Things Growing in a Churchyard" and "Transformations" it's a sunny graveyard where the dead are busily and happily turning into green shoots on the yew tree or "entering this rose." Hardy starts with the familiar and uninspiring idea of pushing up daisies and makes it work. There is nothing of Dylan Thomas's windy, rhetorical assertion that "Though they be mad and dead as nail/Heads of the characters hammer through daisies." Instead he lets the characters speak for themselves and populates a heaven that is actual:

- I am one Bachelor Bowring, 'Gent,' |

|

Sir or Madam; |

|

In shingled oak my bones were pent; |

|

Hence more than a hundred years I spent |

|

In my feat of change from a coffin-thrall |

|

To a dancer in green as leaves on a wall, |

|

All day cheerily, |

|

All night eerily! |

|

It is this idea of naturalised immortality that Eliot is partly slighting in "The Dry Salvages" when he says:

We, content at the last If our temporal reversion nourish (Not too far from the yew-tree) The life of significant soil. |

Eliot means that significance is not one of the properties of soil, but Hardy gives distinct human personalities to some of the plants and trees it nourishes and so suggests that it is meaningful. Bowring's gruff certainties and self-importance follow Fanny Hurd's twittering meekness, Thomas Voss has "turned to clusters ruddy of view" and Lady Gertrude is splendid in laurel. Each speaker has a unique voice, a "murmurous accent," as well as surviving naturally and visibly. Again, this positivistic concept of immortality is also social because people who move in society must be seen in order to be. But underneath the robust social comedy of the graveyard there is also a mysteriousness and an ecstatic energy. It's there in the "radiant hum" and dancing freedom of "Voices from Things" and at the end of "Transformations" where

they feel the sun and rain, |

|

And the energy again |

|

That made them what they were! |

|

The physical basis of life gives Hardy no cause for despair in these poems and unlike Eliot he feels no need to reject a non-significant biological materialism, for it enables him both to create character and imply the forces underlying it. . . But in both "Transformations" and "Voices from Things" there is a quality somewhere around the edges of this eventually constraining positivistic humanism which is liberating and totally imaginative (and just in this instance I'm identifying humanism with social comedy). There is a kind of witty seriousness beyond the comedy of Bachelor Bowring and Lady Gertrude." (Paulin, 32-4)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Moments of Vision

- Collection of 160 poems written by Thomas Hardy.

- Published in November of 1917 by Macmillan and Company.

- This volume is the largest collection of poems Hardy published.

- 15 of the poems had been previously published. Nine within Selected Poems of Thomas Hardy.

- The collection contains several poems attributable to the loss of Hardy's first wife Emma.

- Hardy inscribed a copy to Florence Hardy, his second wife. "From Thomas Hardy, this first copy of the first edition, to the first of women Florence Hardy. Nov. 1917"

(Wright, 220)

Hardy commented about the volume saying, "I do not expect much notice will be taken of these poems; they mortify the human sense of self-importance by showing, or suggesting, that human beings are of no matter or appreciable value in this nonchalant universe." (Pinion, 120)

F. B. Pinion comments about the poetry saying, "most are reminiscent; many are inspired by the memory of Emma Hardy." (Pinion, 120)

Gerald Finzi set the following poems within this collection:

- At Middle-Field Gate in February (I Said To Love)

- The Clock of the Years (dated: 1916) (Earth and Air and Rain)

- For Life I Had Never Cared Greatly (I Said To Love)

- In the time of 'The Breaking of Nations' [titled by Finzi as: Only a man harrowing clods]

- It Never Looks Like Summer (dated: March 8, 1913) (Till Earth Outwears)

- Life Laughs Onward (Till Earth Outwears)

- Overlooking The River Stour [titled by Finzi as: Overlooking the River] (Before and After Summer)

- The Oxen ( By Footpath and Stile)

- Paying Calls (By Footpath and Stile)

- Transformations (A Young Man's Exhortation)

- While Drawing in a Churchyard [titled by Finzi as; In a Churchyard] (Earth and Air and Rain)

Helpful Links:

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Musical Analysis

Composition date: 1929 (Banfield, 144)

Publication date: Copyright 1933 by Oxford University Press, London. Copyright © assigned 1957 to Boosey & Co. Ltd. (Finzi, 162)

Publisher: Boosey & Hawkes - distributed by Hal Leonard Corporation

Tonality: The song begins in G major and ends in D major. A modulation to D major occurs in measure twenty-seven with the simple addition of C-sharp in the piano accompaniment. Finzi remains in D major and ends the first section in measure thirty-two with a D major chord. The next section begins in G major and remains so until measure forty-two with the inclusion of C-sharp again in the piano accompaniment. The remainder of the song is in D major. Finzi doesn't fully cadence, in a traditional sense but instead simply ends on a D major chord just as he did the first section. For additional information about the original key please refer to: Tonality - Van der Watt.

Transposition: Currently unavailable.

Duration: Approximately one minute and twenty-four seconds.

Meter: The song is in 2/4 throughout. For additional information about the meter within the song please refer to: Metre - Van der Watt.

Tempo: The opening indication is Con moto with the quarter note equalling c. 72. The first deviation from the opening indication is in measure twenty-two where a poco ritard is indicated supporting the text "for repose" after which a pochissimo meno mosso is indicated at the end of measure twenty-three. A ritard is at the end of measure twenty-nine which corresponds with the end of the second stanza. In second-half of measure thirty-two an a tempo is indicated to begin the introduction for the third stanza.

Mark Carlisle makes some suggestions about the tempi in his "comments about performance" section of his dissertation: "The initial tempo marking of [quarter note] = c. 72 is really quite good, though some minor variation in either direction is certainly acceptable. However, performers should be aware of two points regarding tempo: 1) the slowness of harmonic rhythm can only be accentuated and create listener disinterest if the tempo is substantially less than indicated; and 2) one that is too much faster can result in enunciation problems for the singer that can also cause listener disinterest due to a lack of textual intelligibility. Therefore, it is imperative that performers consider the matter of tempo with great discretion, especially if any serious deviations from the suggested marking are contemplated." (Carlisle, 170) To view Dr. Carlisle's comments in total please refer to: Carlisle - Comments about Performance. For additional information about the tempi please refer to: Speed - Van der Watt.

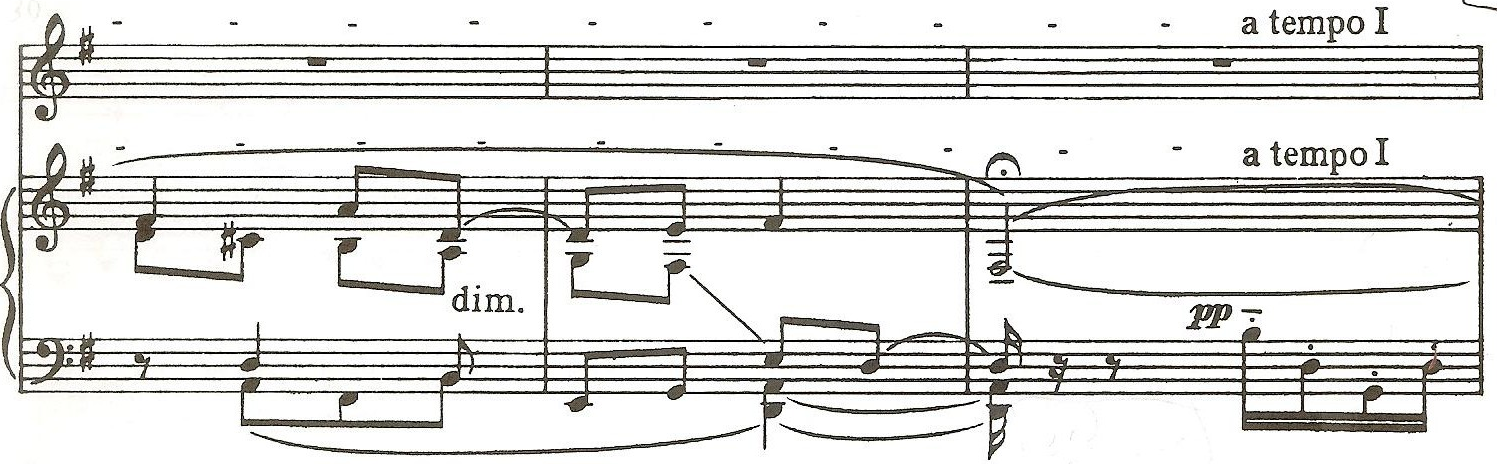

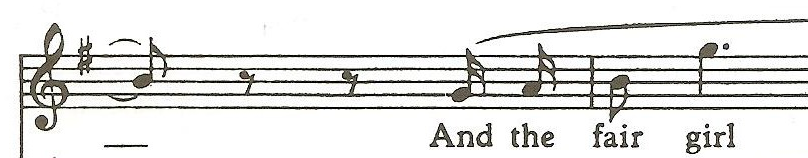

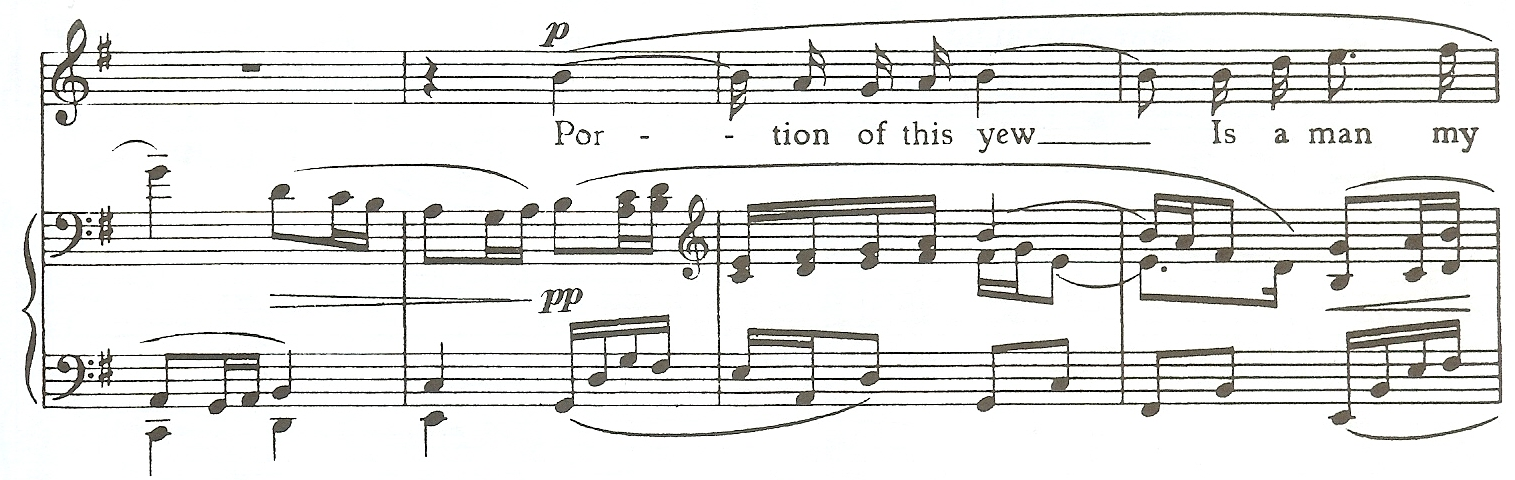

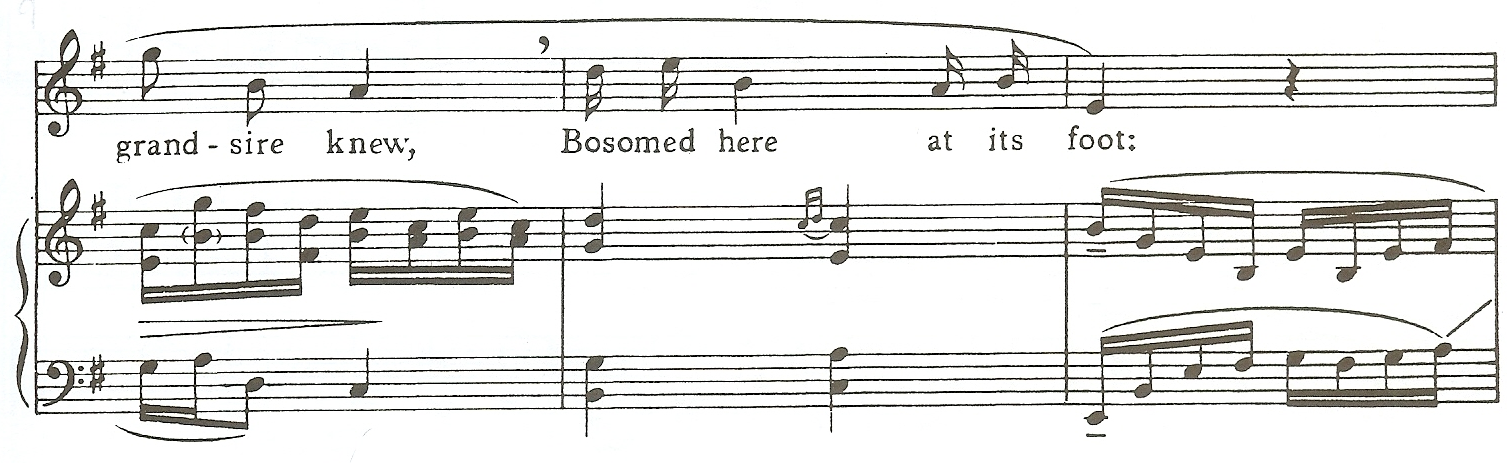

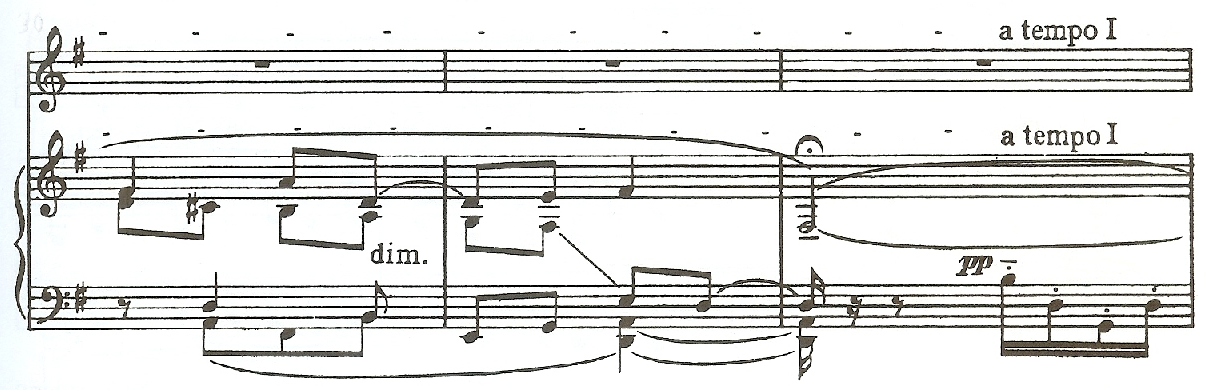

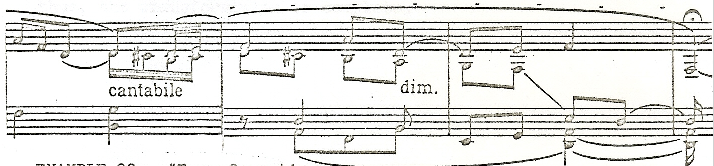

Form: The song is through-composed. The sections of the song follow the structure of the poem with a clear break between the second and third stanzas in measure thirty-two. There are also interludes that help delineate the structure of the poem, the longest coming between the second and third stanzas, reminiscent of the piano preludes running sixteenth notes (see example below).

End of second stanza and connecting interlude for the third stanza, measures 30-5.

(Finzi, 164)

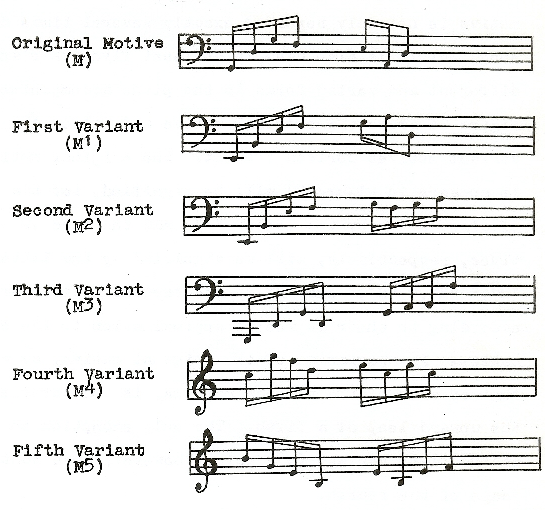

Carl Rogers writes in his thesis with regards to unifying material, "The feeling of unity in the music is engendered by the intermittent exact repetition of several of the motivic figures, and yet variety too is achieved by varying slightly the intervals found in the motives from time to time. A short motive is stated in the first measure of the piano accompaniment. This original motive is not only repeated exactly several times during the song, but it is also used in at least five other somewhat different and varied forms in the piano accompaniment." (Rogers, 56) Dr. Rogers uses a table to illustrate the various forms of the unifying motifs and to see it please refer to: Motifs - Rogers. Michael Bray also speaks to the motifs Finzi uses in the song in his thesis. To view Dr. Bray's comments please refer to: Comments - Bray. Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt has also prepared a table illustrating the specific sections of the song as well as other comments about the form. To view Dr. Van der Watt's table please refer to: Structure - Van der Watt.

Rhythm: The most prominent rhythmic feature of the song is Finzi's use of the sixteenth note and the contrast created when the rhythmic durations lengthen in order to emphasize the text. Several authors that have analyzed this song speak of the various motifs that Finzi uses in the course of the song and these rhythmic motifs unify the song. To view the various motifs please refer to: Motifs - Rogers. For additional comments about the rhythm and the rhythmic motifs of the song please refer to: Rhythm - Van der Watt.

A rhythmic duration analysis was performed for the purpose of tabulating the types of rhythms as well as the number of occurrences. To view the results please refer to: Rhythm Analysis. The information contained within the analysis includes: the number of occurrences a specific rhythmic duration was used; the phrase in which it occurred; the total number of occurrences in the entire song.

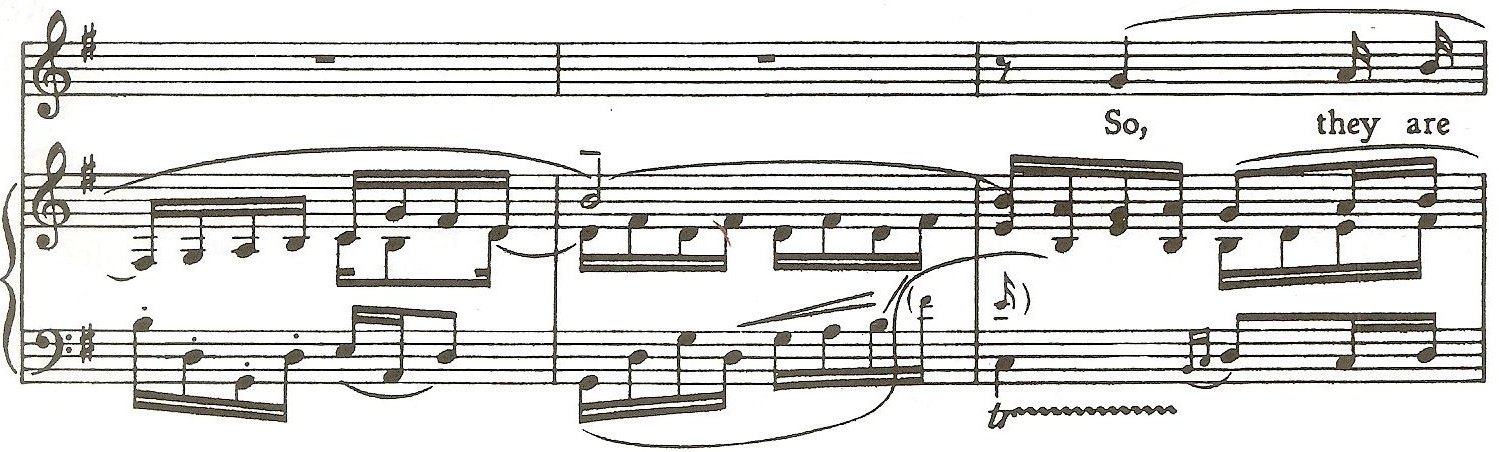

Melody: The vocal line is constructed in a typical Finzi manner with step-wise motion as well as small leaps. The larger leaps are used to emphasize the text. The largest leap, an ascending octave occurs at the beginning of the last line of the poem on the text "That made them what they were!" in measures forty-four and forty-five (see example below). The other two large leaps are both ascending minor sixths and again are used to highlight the text (see examples below).

Octave leap in the vocal line in measures 44-5. (Finzi, 165)

Ascending minor sixth leap in vocal line in measure 25. (Finzi, 164)

Ascending minor sixth leap in vocal line in measure 37. (Finzi, 165)

As was mentioned in the "rhythm" category above, the most prominent melodic feature can also be found in the motifs in the song. To see the various forms as well as a table of locations please refer to: Motifs - Rogers. For additional information about the melodic material within the song please refer to: Melody - Van der Watt.

An interval analysis was performed for the purpose of discovering the number of occurrences specific intervals were used and also to see the similarities if there were any between stanzas. Only intervals larger than a major second were accounted for in the interval analysis. For a complete description of the results of the interval analysis please see the table at the bottom of the page or click on: Interval Analysis.

Texture: The texture utilizes both contrapuntal writing as well as homophonic. For a brief description about the texture including a table outlining the types of texture and the percentage in which they were used please refer to: Texture - Van der Watt.

Vocal Range: The vocal range spans an interval of a perfect twelfth. The lowest pitch is the D below middle C and the highest pitch is the A above middle C.

Tessitura: The tessitura spans an octave from the G below middle C to the G above middle C. A pitch analysis was performed for the purpose of accurately determining the tessitura and for the complete results please refer to: Pitch Analysis.

Dynamic Range: The dynamic range spans from pianissimo at the beginning of the song to triple forte in the last two measures of the piano accompaniment. There are frequent indications for dynamic change both in the piano accompaniment and vocal line. For a discussion about dynamics including a table listing where each dynamic is indicated within each stanza please refer to: Dynamics - Van der Watt.

Accompaniment: The accompaniment is extremely active throughout the song and as such is difficult. There are also several shifts in tempi that are particularly sympathetic to the vocal line. Another difficulty is the dynamics, one must not overpower the vocalist in the midst of the frenzied sixteenth notes. For additional comments about the accompaniment please refer to: Accompaniment - Van der Watt.

Pedagogical Considerations for Voice Students and Instructors: The range of this song is no higher than many in this set but the tempo is much faster than most of Finzi's songs and the use of rhythm is slightly more complex. Compounding matters of difficulty are some of the approaches to the high notes in the song and the irregularity of phrase lengths. Good breath management as always is important but especially so in this song. In measure seven on the word "yew" one will need to monitor the breath flow and not allow the support to sag. Locating the longer note values and paying close attention to support while singing them may help alleviate breath problems throughout the song. In measure thirteen observe the support on the word "wife" being careful to not go to early to the diphthong or spread the vowel. The same observation should be made in measure fourteen with the word "life." While both of these spots are not high in the voice they are critical in the set-up for the high notes that come after. Once the larynx becomes high or tension in the jaw and tongue set-in it is almost impossible to free them while performing. In measure twenty-five, with the word "girl" be careful to not "chew" on the [r] consonant. The same observation needs to be made in measure thirty-seven with the word "nerves." Lastly, the octave leap to the high [A] at the beginning of measure forty-five is a nice set-up but the [e] vowel may cause some difficulty. Try modifying the vowel to [E] if the [e] seems tight. If the vowel is spreading try mixing toward the [i] vowel with ample space above the tongue. Observation should also be made of the corners of the mouth so as to insure the spreading is not happening there as well. A good fix for relaxing the corners of the mouth is to think "taller" inside the mouth while monitoring the jaw for any tension.

Dr. Mark Carlisle records in his dissertation the following observations and advice: "This song, for all of its basic homogeneity and directness, still contains some of the more difficult technical and musical demands found in this cycle. While range and tessitura requirements in general are not the most demanding, the emphasis on expansive, angular melodic leaps around the tenor passaggio can easily cause many technical problems for a young singer. Dynamic and dramatic expectations at the end of the song are substantial, yet the singer must also have the technical facility to handle the variety of inherent rhythmical and enunciatory problems. This dichotomy is not necessarily unique in Finzi's song output, but it inevitably limits the pool of potential performers capable of presenting an exciting rendition of this piece. A talented, intelligent, technically secure junior or senior in college would most likely be capable of providing a very fine performance, but the song does have the potential to cause problems for even graduate students. Those considering its inclusion in their repertoire would do well to familiarize themselves with its inherent difficulties before assuming that it is an easy piece to sing. Its potential hazards can be discouraging for those incapable of surmounting them, but its wonderfully exuberant, extroverted personality highly appealing and worth the effort for those with the requisite capabilities." (Carlisle, 172)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Below one will find excerpts from unpublished dissertations. The excerpts should provide a more complete analysis of Transformations for those wishing to see additional detail. Please click on the link or scroll down.

Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

Michael R. Bray - An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

| Pitch Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pitch | stanza 1 |

stanza 2 |

stanza 3 |

total | |

highest |

A |

1 |

1 |

||

G |

2 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

|

F |

1 |

2 |

5 |

8 |

|

E |

5 |

4 |

6 |

15 |

|

D |

7 |

8 |

5 |

20 |

|

middle C |

1 |

4 |

4 |

9 |

|

B |

7 |

10 |

9 |

26 |

|

A |

5 |

5 |

4 |

14 |

|

G |

4 |

4 |

4 |

12 |

|

F |

1 |

1 |

|||

E |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

lowest |

D |

1 |

1 |

||

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Audio Recordings

The Songs of Gerald Finzi to Words by Thomas Hardy

|

|

|

|

Gerald Finzi Song Collections |

|

|

|

The English Song Series - 16 |

|

|

|

Song Cycles for Tenor & Piano by Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

Songs by Britten, Finzi & Tippett |

|

|---|---|

|

|

Songs of the Heart: Song Cycles of Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

The following is an analysis of Transformations by Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt. Dr. Van der Watt extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on October 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated November 1996, is entitled:

The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt comes from Volume II and begins on page one hundred forty-three and concludes on page one hundred fifty of the dissertation. To view the methodology used within Dr. Van der Watt's dissertation please refer to: Methodology - Van der Watt.

1. Poet

Specific background concerning poem:

"The poem comes form Moments of Vision (1917). Seymour-Smith suggests that Hardy wrote this poem largely as a result of the death of Louisa Harding (1913), a girl he "seems to always have worshipped from afar". Seymour-Smith continues:"

(Van der Watt, 143)

"After her death in 1913, at the age of seventy-two, he used often to ponder over her (unmarked) grave in Stinsford churchyard. As a result of one such visit there he wrote 'Transformations' . . . According to a note inserted into the Life by Florence (on advice of James Barrie), young Tom never said more than 'good evening' to Louisa, and she never uttered a word to him . . . her parents would not allow her to have anything to do with him on the grounds of his social inferiority . . . Louis, as her family called her, lived in Dorchester all her life, but never tried to call on her old admirer when he became famous - nor he on her, although he may well have seen her in the street." (Seymour-Smith, 31-2) (Van der Watt, 143) |

2. Poem

"The poet, having visited a graveyard, reflects on what has become of the deceased. He suggests they are not just dead and buried, but that they have grown into the vegetation in the graveyard; a type of natural re-incarnation. A man and his wife, belonging to his grandfather's generation, may have grown into a yew tree, and a pious woman into some grasses. A girl, Louisa Harding whom Hardy as a youngster worshipped from afar, may be transforming into a rose. In this way the deceased are not dead but have achieved a re-incarnation by living on in nature by the same energy that brought them into human existence."

(Van der Watt, 143)

"The poem has a pastoral, lyrical style with a religious-philosophical under current or intention."

(Van der Watt, 144)

"The poem consists of three sestets with lines of Uneven length. The rhyme scheme is a mixture of paired and rounded rhyme: aabccb ddeffe gghiih. The metre is mainly trochaic and iambic."

(Van der Watt, 144)

"The idea of "natural" re-incarnation recurs in Hardy's poetry. The third stanza of the poem "Drummer Hodge" (Poems of the Past and the Present (1901), War Poems) reads as follows:"

Yet portion of that unknown plain |

Will Hodge forever be; |

His homely Northern breast and brain |

Grow to some Southern tree, |

(Hardy, 91) |

"In "Transformations" as in "Drummer Hodge", the re-birth after death through unity with nature, is presented in a very positive light. A sense of excitement accompanies the thought that the deceased have found a new energy of existence in nature. The simplicity in style, form and imagery, results in an almost childlike acceptance of familiar people being re-incarnated into a tree, some tufts of grass or a rose."

(Van der Watt, 144)

Setting

1. Timbre

VOICE TYPE/RANGE

"The song is set for tenor voice and the range is a perfect twelfth from the first D below middle C."

(Van der Watt, 144)

"The treble clef part only moves outside the confines of the stave from bars 44 - 47 with the climax in bar 46, a B three octaves above middle C. The bass clef part reaches its lowest pitch (the third D below middle C) at the same moment. Other notes below the stave are few except for the opening bar. Here the right hand part is notated in the bass clef for six bars. The piano sonority, initially, favours the lower register then moves into the middle range until bar 42 and ends with an ecstatic exploration of the extreme sonorities of both of both right and left hand parts."

(Van der Watt, 144)

"There are no indications for the use of pedal. The implication is that pedalling remains the responsibility of the performer since it is clearly necessary to use the pedal. Legato touch is required for large portions of the accompaniment (b. 1-13, 20-31, 34-39) but there is also a variety of other articulation indications. Portamento accents are used mildly to emphasize certain notes (b. 2, 5, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 18, 32, 34 and 40). Stronger accents are used in two separate places: Bars 15 -16 with the text, "Now turned to a green shoot" and bars 46 - 47 on the word, "were" (from the line, "That made them what they were", the climax of the poem). There are three different staccato indication: Half-staccato (b. 17 and 32), Staccato (b. 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 33, 33 and 40) and Staccatissimo (b. 43 and 44). The staccato touch results in a heightened sense of excitement especially in bars 43 - 44."

(Van der Watt, 144)

"There are three trills in the bass part: bar 14, on the words "ruddy human life", bar 16, after the word, "Shoot", bar 35 at the start of the final stanza. These suggest a kind of rumbling movement beneath the surface as though those underground are actually growing towards the "upper air"."

(Van der Watt, 145)

"The atmosphere created by the piano accompaniment relies on the fairly swift tempo (Con moto [quarter note equals] c. 72), the modulations to the dominant (G - D major), the active rhythmic material and the above mentioned utilization of the piano sonorities. The prelude starts in the lower register (with both parts notated in the bass clef for six bars after which the right hand part slowly makes it way into [the] higher register and eventually ends in the extremely high register. This setting is very effective due to the fact that the entire meaning of the poem has been translated directly into music: the deceased have grown, out of their graves, into the vegetation in the graveyard. The first modulation occurs at the mention of the "fair girl" whom Hardy "often tried to know" (l. 11) and the second modulation occurs with the words "and the energy again". In both cases the exuberance is enhanced by the modulation to the dominant. The excitement created by the second modulation is further reinforced by a quicker harmonic rhythm and staccatissimo touch (b. 43-46). The general atmosphere of the song is that of slowly growing vibrancy."

(Van der Watt, 145)

2. Duration

"The trochaic and iambic metres of the text are matched with a simple duple time-signature which is retained throughout. The accents in bars 15-6 have a slight and brief metric impact with the words "Now turned to a green shoot". The metric instability is directly related to the textual meaning: form "ruddy human life" to "green shoot". The rest of the song has a strong metric drive which is supportive of the growing revelation in the song."

(Van der Watt, 145)

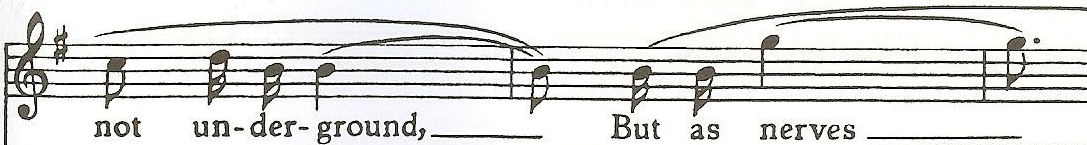

Rhythmic motifs

"The rhythmic motif consisting of four semi-quavers (motif 1) occurs 72 times, mainly in the piano part. The basic forward movement of the song is derived from this motif. Motif 2, consisting of two quavers, occurs 35 times, mainly in the piano part. This motif, with exceptions (b. 43-46), is the main carrier of the harmonic rhythm. Motif 3 consists of a quaver and two semi-quavers and occurs 21 times (b. 1, 3, 4(2), 5(2), 6(2), 8, 12, 13, 14, 23, 27, 29 35(2), 36, 37, 39, 46). Motif 4, consisting of two semi-quavers and a quaver, occurs 18 times in both piano and voice (b. 1, 7(2), 8, 9, 10, 24, 26, 27, 28(2), 29, 33, 36(2), 38, 40). These two motifs (3 and 4) are merely rhythmic variations on the first two and provide a slightly less active rhythmic movement where they occur. Motif 5 consists of two crotchets and occurs 14 times in the piano part only (b. 3, 4, 5, 10(2), 23, 25(2), 26(2), 28, 29, 39(2)."

(Van der Watt, 145)

"A number of rhythmic accents occur through syncopation (b. 6, 18, 22, 35). three of these are at the opening of each stanza and serve to emphasize the beginning of the stanza."

(Van der Watt, 145)

Rhythmic activity vs. Rhythmic stagnation

"The rhythmic activity is mostly that of four semi-quavers but there are isolated bars that slow down to either crotchet or quaver movement (b. 10, 15-6, 25-6, 30-2, 39, 47). The stagnation mainly occurs in the piano part which leaves the vocal part more exposed and thus, emphasized."

(Van der Watt, 145)

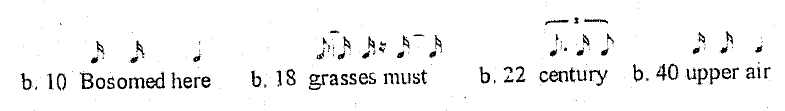

Rhythmically perceptive, erroneous and interesting settings

(Van der Watt, 146)

Lengthening of voiced consonants

"The following words containing voiced consonants have been rhythmically prolonged in order to make the word more singable:"

(Van der Watt, 146)

"The tempo indication is Con moto [quarter note equals] c. 72. Tempo deviations are listed below:"

Bar no. |

Deviation |

Bar no. |

Return |

Suggested reason/s |

22 |

poco rit. |

23 |

pochiss. meno mosso |

Anticipate the section about the girl |

29 |

rit. . . |

32² |

a tempo I |

Original material, final stanza |

41-2 |

poco a poco piu animato |

44 |

Allargando |

Meaning emphasized, end anticipated |

3. Pitch

Intervals: Distance distribution

Interval |

Upwards |

Downwards |

Unison |

(11) |

|

Second |

40 |

28 |

Third |

5 |

12 |

Fourth |

3 |

4 |

Fifth |

2 |

2 |

Sixth |

3 |

2 |

Octave |

1 |

0 |

"There are 11 repeated pitches (or 10% of the total number), 54 rising intervals (or 48%) and 48 falling intervals (or 42%). The smaller intervals (a third and smaller) account for 96 intervals (85% of the total number) while the larger intervals (fourths and larger) account for 17 (or 15%). The interval of a downward third has a prominent recurrence largely due to an arpeggiated melodic line in certain places (b. 15², 26¹, 40¹). In a vocally conservative circumstance such as this, larger intervals tend to be of greater significance."

(Van der Watt, 146)

Interval |

Bar no. |

Word/s |

Reason/s |

6th down |

9 |

grandsire |

Emphasis |

5th down |

11 |

its foot |

Reinforce meaning |

6th up |

12 |

be his |

Emphasis |

4th up 4th down |

14-5 |

life Now turned |

Emphasis, reinforce emotional content |

5th down |

19²b |

made of |

Emphasis |

5th up |

19¹ |

grasses |

Emphasis |

4th down 5th up |

23 |

for repose |

Emphasis |

6th up 4th down |

25-6 |

fair girl long |

Emphasis, reinforce emotional content |

6th up |

37 |

as nerves |

Emphasis |

4th up 3rd down |

41 |

the sun and |

Reinforce meaning |

6th down 8th up |

44-6 |

again that made |

Reinforce emotional content, emphasis |

Melodic curve

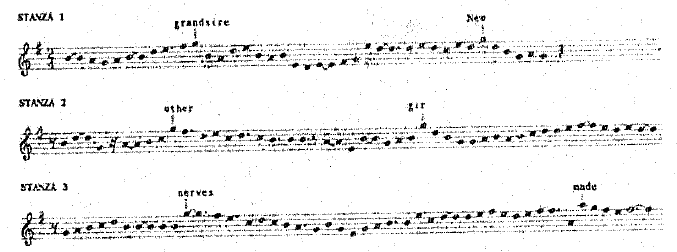

"A melodic curve of the vocal line is represented below. Certain words are indicated to show the relationship between the melodic curve and the meaning:"

(Van der Watt, 147)

(Van der Watt, 147)

Climaxes

"There is a single climactic instance in the song namely the A in bar 45 on the word "made", very close to the end of the song. The placing of the climax at the end tallies with the gradual development of the excitement in the song. The climax is further strengthened by the fact that it is preceded by a pitch an octave lower."

(Van der Watt, 147)

Phrase lengths

"The following suggestions some of which are the composer's, are made with regard to breathing."

Stanza 1 (b. 6-16) |

Breathe at bar 9 (composer's indications) and 13² |

|

Stanza 2 (b. 18-29) |

Breathe at bar 27² (composer's indication) |

|

Stanza 3 (b. 35-47) |

Breathe at 37¹, 40², 44² |

"The song starts in G major and ends in the dominant, D major. All modulations are summarized below."

(Van der Watt, 147)

Bar no. |

From - To |

Suggested reason/s |

27² |

G maj - D maj |

Heightened excitement at mentioning the "fair girl" |

32 |

D maj - G maj |

Return to original material in final stanza |

42 |

G maj - D maj |

Anticipate the reference to "energy", emotional excitement |

Chromaticism

"There is no chromaticism in the song other than at the moment of modulation."

(Van der Watt, 148)

HARMONY AND COUNTERPOINT

"A strong relationship is established between chords I and ii or their inversions (b. 3¹b-7¹a, 9²b-10², 22²-23², 24²-25¹, 31, 38²b-39², 42²b-43¹). Scores of triads are furnished with sevenths and occur in second inversion. There is also the occasional triad extended to the ninth (b. 9¹a, 41²b, 42²b, 44¹b&²b). The final cadence is interesting in that its progression is from iii₆ - I, a varied perfect cadence."

(Van der Watt, 148)

Non-harmonic tones

"Non-harmonic tones are used freely as part of the general melodic and contrapuntal procedures. No specific consistent usage can be directly related to the meaning."

(Van der Watt, 148)

Harmonic devices

"There are no pedalpoint notes held longer than a minim tied to a quaver (b. 2-3, 17-8, 32-3, 34-5, 46-7 (voice)). These have no direct relation to meaning of the text."

(Van der Watt, 148)

Counterpoint

"There is a stronger tendency towards homophonic, chordal accompaniment than to free contrapuntal procedures. There are small imitations between piano and voice: bars 28-9 voice - bars 29-30 piano (alto part) and bar 43 voice - 43² piano (upper part). In the piano internally, there is an imitation in bars 3 - 6 between the upper part of the right hand and the upper part of the left hand material."

(Van der Watt, 148)

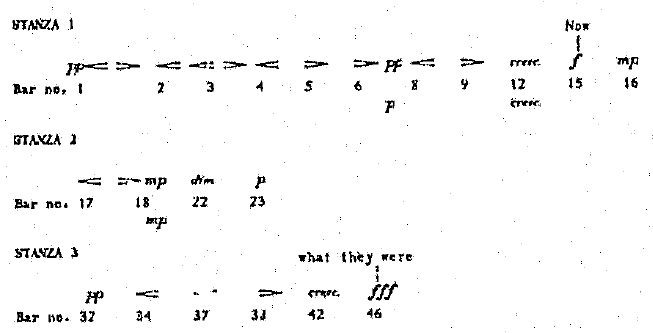

"Loudness variation is given in the following summary:"

(Van der Watt, 148)

(Van der Watt, 148)

FREQUENCY

"There are 29 indications in the 47 bars. Some bars do not contain indictions while others contain more than one. There are only three separate indications for the voice which means that the voice should follow the indications given in the piano part where there are no separate indications."

(Van der Watt, 148)

RANGE

"The pp indication is used three times (b. 1, 6, 32) and is the lowest indicated level. The highest dynamic level is the fff indication in the second last bar (b. 46) on the piano climax of the setting. It is interesting to note that the lowest level occurs in the opening bar and the highest level in the penultimate bar. These dynamic indication support the other elements in the development of a gradual increase in excitement from beginning to end, low to high, "underground" to "upper air"."

(Van der Watt, 148-9)

VARIETY

"The indications used are:"

(Van der Watt, 149)

DYNAMIC ACCENTS

"Apart from a number of portamento accents, which have already been listed, stronger dynamic accents are used in two isolated places: in bars 15-6 the accent derails the metre somewhat and is related to the text in that quite a change has to take place between the "ruddy human life" and the "green shoot" into which it is transformed. Bars 46-7 form piano climax of the song and the accents enhance the strong drive of energy mentioned in the preceding text. This energy is the same life-giving force that originally brought into existence the people about whom the poet is writing."

(Van der Watt, 149)

"The density varies loosely between two and eight parts including both piano and voice. The thickness of the piano part is represented in the following table:"

No. of parts |

No. of bars |

Percentage |

2 parts |

9 |

19 |

3 parts |

20 |

43 |

4 parts |

13 |

28 |

5 parts |

2 |

4 |

6 parts |

2 |

4 |

7 parts |

1 |

2 |

"Again, the most significant observation is that the opening bar is in two parts and that the final chord has seven different pitches. The same sense of textural build-up as in the dynamic development is noticeable here, especially in the last eight bars:"

Bar 40 |

Two part |

|

Bar 41-2 |

Three part |

|

Bar 43 |

Four part |

|

Bar 44 |

Five part |

|

Bar 45 |

Six and four part |

|

Bar 46 |

Five and six part |

|

Bar 47 |

Seven part |

"With the mention of the "energy" which will re-incarnate the deceased into nature, the textural thickness of the piano part is intensified."

(Van der Watt, 149)

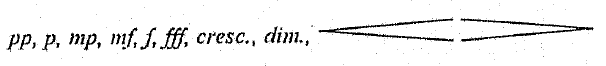

"The structure of the song is represented in the following table:"

(Van der Watt, 150)

(Van der Watt, 150)"The song has a ternary form with the vocal and piano parts of the second. A quite extensively modified, especially towards the end."

(Van der Watt, 150)

7. Mood and atmosphere

"The song starts with an atmosphere of suppressed excitement which develops gradually to an ecstatic celebration of life in the final bars. The animation is largely carried by the semi-quaver rhythmic movement and is enhanced by two modulations to the dominant key. The dynamic and textural usage towards the end of the song reinforce the belief that the deceased has become on with nature through the same "energy" which "once awoke the clay of this cold star", to use Wilfred Owen's phrase from the poem, "Futility"."

(Van der Watt, 150)

General comment on style

"The setting is very voice-friendly with 85% smaller intervals in the vocal part. The harmonic language is tonal and restricted to two related keys, G and D major. The atmospheric setting is tightly controlled to really peak in the final line of text and this results in an effective emphasis on the climax of the poem. A strong sense of forward drive is established through the use of active rhythmic motifs. The musical transformation that takes place in the song as suggested by the title, is largely reserved for the final eight bars where dynamics, texture and tempo indication cooperate to achieve an effective exuberance."

(Van der Watt, 150)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Transformations by Mark Carlisle. Dr. Carlisle extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 7th, 2010. His dissertation dated December 1991, is entitled:

Gerald Finzi: A Performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and Piano to Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page one hundred sixty-three and concludes on page one hundred seventy-two of the dissertation.

Comments on the Poem

""Transformations" was published in 1917 as part of the collection Moments of Vision, and has, in its manuscript form, the subtitle, "In a Churchyard." Hardy identified this "churchyard" as a cemetery at Stinsford, about a mile and a half northeast of Dorchester. (Purdy, 198) The poem shows us a glimpse of some of Hardy's deepest spiritual convictions. As an agnostic and self-proclaimed realist, he could not believe in a biblical afterlife, but instead found reassurance in the belief that mankind lives on in a physical sense by becoming food for the life around him. This is evident from the fact that Hardy owned and read T. H. Huxley's essay, "The Physical Basis for Life," which states, "There is a sort of continuance of life after death in the change of the vital animal principle, where the body feeds the tree or the flower that grows from the mound." (Ransom, 187) This concept of immortality today might seem morbid to staunch Christians, but for Hardy it was a concept in which he found much comfort."

(Carlisle, 163-4)

"Finzi's setting of 'Transformations' represents a substantial contrast to those preceding it, as for only the second time in this cycle the emphasis is on a continuously rapid pace and varied rhythmical patterns, particularly in the melody. Its personality is highly extroverted, with little if anything that could be considered subtle. It is certainly one of the least complicated of all of his songs; from beginning to end there is very little textural variation and only simple, harmonic changes. While melodic structure and phrasing does vary often, it is clearly under the influence of rhythmical interests and lacks the graceful style heard in many of Finzi's songs. Not since the third song of the cycle, 'Budmouth Dears,' has there been such energy to a song almost completely supplied by the external factors of tempo and rhythm, and it is very refreshing."

(Carlisle, 164)

"The piece is forty-seven measures in length, divided into two parts by a change of tempo and a conclusive harmonic cadence in the dominant. Part two, which begins in measure 32, is a slightly varied restatement of the first part, with measures 33-34 reflecting measures 1-2, and measures 36-40 reflecting measures 7-11. The opening key is G major, changing to its dominant, D major, at the end of each of the two parts, but retaining its prevalence throughout both parts. The time signature is 2/4, which never changes, and while the initial tempo marking of quarter note equals c. 72 predominates, frequent interpretive tempo directions appear throughout both parts."

(Carlisle, 165)

"The first part is the longest of the two, incorporating thirty-two of the song's forty-seven measures and two of the three poetic stanzas. It begins with a prelude of five and a half measures that define the basic rhythmic and textural character of the entire piece. Sixteenth-note patterns abound in both hands of the accompaniment, interspersed by some eighth-note and quarter-note activity. It is this 'notiness' that supplies much of the song's swift sense of motion, as well as for the shifting textural panorama. Also important is the gradual but consistent ascent of tessitura in the prelude that continues to some extent after the entry of the voice line. Both hands of the accompaniment begin in the bass clef, but continually rise until the right hand moves into an upper register in measure 7. This may seem relatively insignificant by itself, but in conjunction with the sensation of a fast tempo, provides a considerable amount of vitality to the opening of the piece that is continued by the entrance of the singer."

(Carlisle, 165)

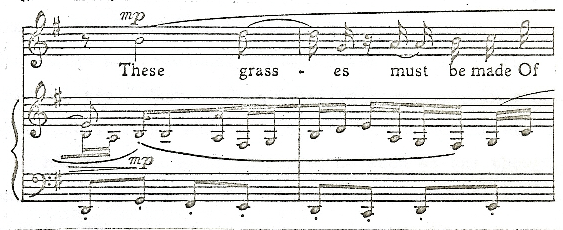

"Example 21. 'Transformations,' measures 1-8." (Carlisle, 166) |

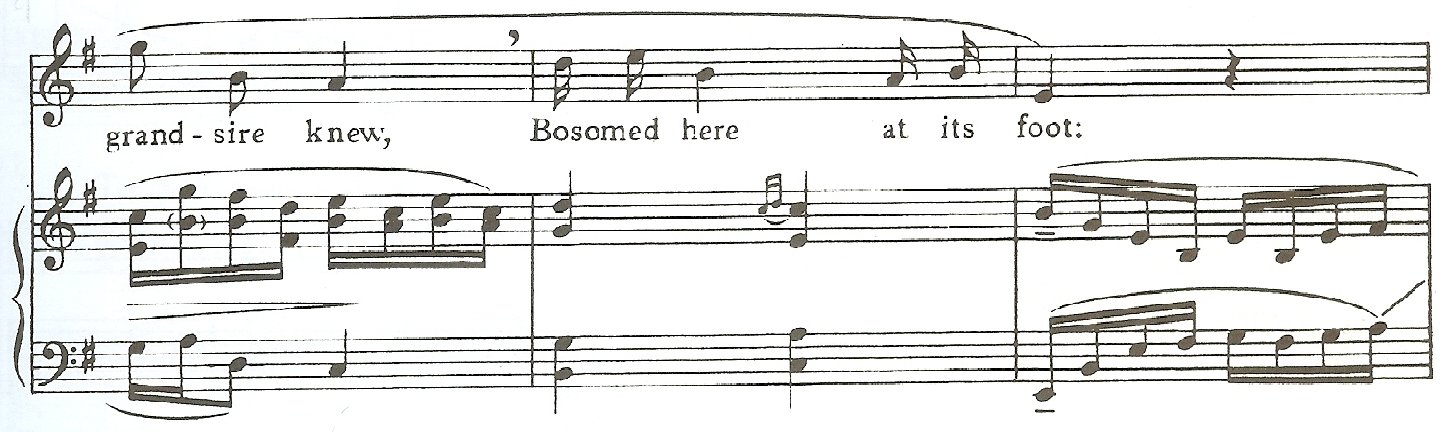

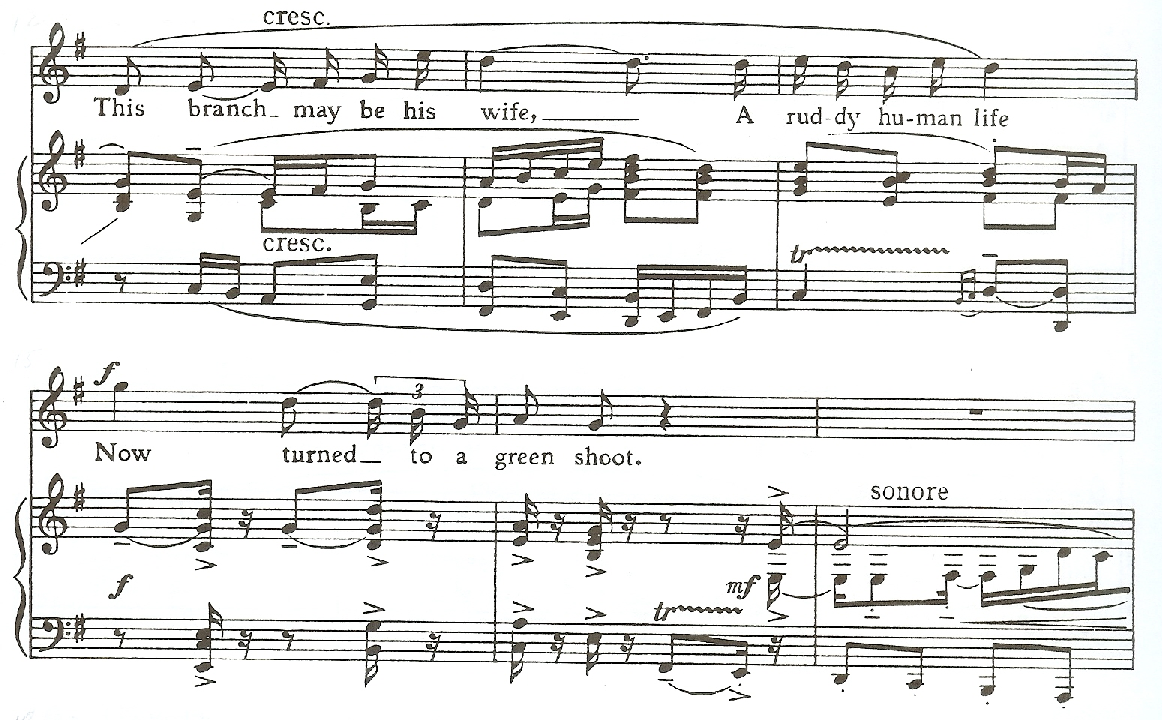

"Melodic shape and phrasing in both sections is characterized by much rhythmical variety, as well as a penchant for more angularity than is customarily heard in Finzi's songs. Melodic rhythms, as always, are quite attuned to the natural stresses of the text, but note values vary often and the use of syncopation is extensive in relationship to other songs. Measures 10, 12, 18, 19, 22, and 26 of the first section, and 35 of section two, all contain moments of melodic syncopation that very quickly focus the listener's attention on the diversity of rhythms involved. The same rhythmical characteristics found in the prelude, sixteenth-note patterns interspersed with eighth-note and quarter-note movement, are also heard in the melody, along with dotted and two brief triplet rhythms. Together they produce a remarkable level of rhythmical excitement and interest that is the foundation upon which this whole song is built."

(Carlisle, 166-7)

"Also important is the quantity of disjunct motion in the song's melodic structure. It is not unusual to see some chordal as well as significant intervallic motion in Finzi's melodies, but rarely do they occur as often as in this song. Measures 9-12, 18-20, 23, and 25-26 of the first section alone contain passages with melodic intervals of a fifth or greater, and more are found in section two. This is not to say that conjunct motion is completely forgotten and unimportant; such measures as 6-8, 13-14, and 27-29 of section one all contain predominantly conjunct movement. However, it is also quite evident that this quality is of considerably less importance than in other songs. Instead, the emphasis on angularity takes precedence, creating a melodic structure emphasizing dramatic utterance over more refined and elegant qualities. This characteristic could in some cases become cloying, but given the basic nature of the piece as a whole, it is most appropriate and certainly quite compelling."

(Carlisle, 167)

"There is little notable diversity in either the harmony or texture of this section, or the entire piece for that matter, but both have some degree of consequence in the overall effectiveness of the song. The opening key of G major remains unaltered until measure 27, at which time is heard a C sharp in the bass line that leads to the key of D major. This modulation lasts until the fermata in measure 32, the end of part one. No other chromatic alterations of any kind are heard in this section, thus causing very static harmonic interest that forces the listener to focus on other more prominent aspects."

(Carlisle, 167)

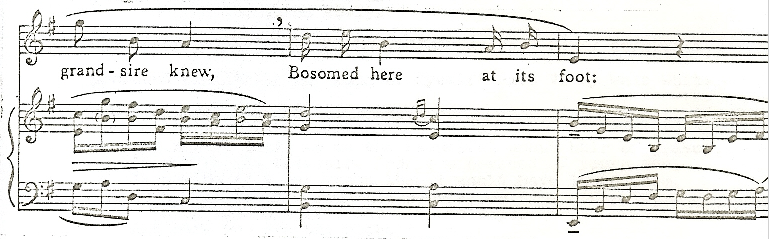

"Textural changes do occur quite often, but they are so dependent upon the aforementioned rhythmical aspects that it is difficult to discern any particular uniqueness about them. Thickness of texture varies somewhat from measure to measure, but in reality the quality of the variation is diminished by the rapidity of change. A mixture of sixteenth-note arpeggiated chords, strict homophonic chords, and those that represent a combination of the two, all of which can be seen in Example 22, blend to become a comprehensive textural portrait that is made considerably stronger by rhythmical factors."

(Carlisle, 168)

"Example 22. 'Transformations,' measures 9-11." |

"Part two begins with an upbeat arpeggiated G major chord in measure 32, and incorporates most of the same characteristics found in part one. The abrupt harmonic change back to G major immediately following the fermata returns the song to its original key, and two measures of interlude preceding the entrance of the voice line in measure 35 follow to a lesser degree the same melody and virtually the same bass line as heard in the prelude. The vocal melody remains focused on disjunct motion, though perhaps not quite to the extent heard in the first part, and continues its emphasis on rhythmical variety and rapidity of enunciation. It is, in fact, the combination of all the musical components working together at the very end of the song that provides the only concrete difference between the parts."

(Carlisle, 168-9)

"The first measures of part two, measures 32-41, represent little musical difference with their counterparts in part one, but a cadential drive beginning in measure 41 provides for a most exciting and dramatic ending. Once again, via the use of an A-major chord, the song begins a modulation to D major in measure 43 that lasts for four measures before a clear cadence is heard in measure 46 that confirms the new key. The harmonic tension built by this passage is quite strong, and made even more interesting by a reference back to G major on the first beat of measure 45 at a particularly dramatic moment. The passage contains the only important harmonic activity in this section, but it is sufficient to alleviate at least some of the static quality heard in this song."

(Carlisle, 169)

"Melody, texture, and rhythm support the underlying harmonic energy from measure 41 to the end with powerful qualities of their own. The melody maintains a tessitura that is quite high, centering on f¹, and includes an impressive octave leap to a¹ in measure 45 before continuing in conjunct motion to finish in dramatic fashion on f¹. Rhythm becomes a consistent set of sixteenth-note patterns in strict chordal style that keeps a constant vitality to the musical flow. The texture achieves its greatest strength as thick, full chords with increasingly expansive characteristics supply a remarkable sense of musical 'weight' to the final measures. The final stanza of the poem, with its expression of life after death as the 'energy of nerves and veins in the growths of upper air,' is clearly what inspired Finzi's rendition, and the musical means that he used to evidence that inspiration are generally quite convincing."

(Carlisle, 169-70)

"The similarities between this and other songs by Finzi are quite noticeable: syllabic word settings, contrapuntal textures, unpianistic style of piano writing, and a change of key for the ending are all common in his writing. In spite of these similarities, the emphasis on melodic patterns not usually occurring in his works and the constantly driving rhythm make this song stand out in the cycle."

(Carlisle, 170)

"The basic character of the song remains constant from beginning to end, so only a few performance aspects need to be seriously addressed. The initial tempo marking of [quarter note] = c. 72 is really quite good, though some minor variation in either direction is certainly acceptable. However, performers should be aware of two points regarding tempo: 1) the slowness of harmonic rhythm can only be accentuated and create listener disinterest if the tempo is substantially less than indicated; and 2) one that is too much faster can result in enunciation problems for the singer that can also cause listener disinterest due to a lack of textual intelligibility. Therefore, it is imperative that performers consider the matter of tempo with great discretion, especially if any serious deviations from the suggested marking are contemplated." (Carlisle, 170)

"A few dynamic markings are indicated throughout the song, and certainly warrant consideration, but this song's overall effectiveness is not heavily dependent upon extensively controlled dynamic variation. The rapid rise and fall of the melodic lines alone provides much inherent dynamic contrast, and the singer will no doubt supply additional variety in order to facilitate technical demands. Dynamic markings that are easily assimilated into the tempo and rhythmical demands should naturally be observed, but those that are difficult to incorporate for either performer can usually be adjusted as necessary without undue injury to the quality of the performance. The primary recommendation for performers with respect to dynamics in this song is to be sure and calculate the general volume level based upon what can be produced to meet the dynamic and dramatic requirements of the ending. This moment should represent the apex of these demands, so the extent of dynamic changes prior to this point should be gauged accordingly; otherwise, the finish will lack the necessary dramatic "punch."" (Carlisle, 170-1)

"A handful of expression markings are indicated, the most important of which are the poco a poco piu animato and Allargando markings in measures 41-44, and the poco ritardando in measure 23. The former are most important in bringing the song to an exciting and dramatic conclusion, while the latter is needed to permit the requisite sensitivity in expressing the underlying textual sentiment of "searching for repose." Other markings, such as sonore, cantabile, and dolce are also suggested at various points during the song, but although not inconsequential, their inherent subjectiveness in a piece of this nature makes it very difficult to provide any specific recommendations for their use. It is left to the interpretive imagination of the performers to determine the possibility of effectively incorporating such expressive suggestions." (Carlisle, 171-2)

"This song, for all of its basic homogeneity and directness, still contains some of the more difficult technical and musical demands found in this cycle. While range and tessitura requirements in general are not the most demanding, the emphasis on expansive, angular melodic leaps around the tenor passaggio can easily cause many technical problems for a young singer. Dynamic and dramatic expectations at the end of the song are substantial, yet the singer must also have the technical facility to handle the variety of inherent rhythmical and enunciatory problems. This dichotomy is not necessarily unique in Finzi's song output, but it inevitably limits the pool of potential performers capable of presenting an exciting rendition of this piece. A talented, intelligent, technically secure junior or senior in college would most likely be capable of providing a very fine performance, but the song does have the potential to cause problems for even graduate students. Those considering its inclusion in their repertoire would do well to familiarize themselves with its inherent difficulties before assuming that it is an easy piece to sing. Its potential hazards can be discouraging for those incapable of surmounting them, but its wonderfully exuberant, extroverted personality highly appealing and worth the effort for those with the requisite capabilities." (Carlisle, 172)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Transformations by Leslie Alan Denning. Dr. Denning extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated May 1995, is entitled:

A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

The excerpt begins on page sixty-nine and concludes on page seventy-one of the dissertation.

"'Transformations' was originally published in Hardy's 1917 Moments of Vision. The views of both Hardy and Finzi regarding religion have been previously discussed. They surface here in a song which extolls the remains of the departed as part of the environment and the never-ending process of life. This is reflected in Finzi's compact contrapuntal setting."

(Denning, 69)

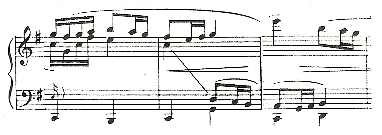

"'Transformations' exists as a direct counterpart to the opening song of Part I, 'A Young Man's Exhortation' in both form and sentiment. Bach's influence is evident from the beginning, but the imitative counterpoint is simultaneously urgent yet compressed. Note the metronome marking of quarter note equals c. 72 (musical Example 13)."

(Denning, 69)

"Example 13: Transformations, Measures 1-4." (Denning, 69) |

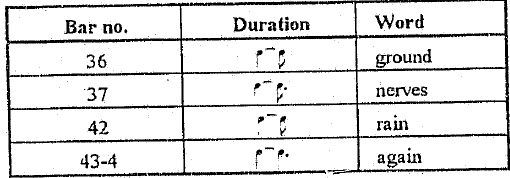

"The vocal line is made up of stepwise motion with small leaps usually followed by textually motivated larger leaps to an accented tone. Occasionally the counterpoint is broken to emphasize the end of a phrase where the composer uses inverted block chords to stop the momentum and then later arpeggiates the tonic or his favored submediant chords to regain movement (musical Example 14)."

(Denning, 69)

"Example 14: Transformations, Measures 9-11." (Denning, 70) |

"The first stanza also shows examples of Finzi's speech-like text setting (musical Example 15)."

(Denning, 70)

"Example 15: Transformations, Measures 12-17." |

"At the end of the second stanza Hardy mentions a decreased former love whom he suggests might be reappearing within the rose. Finzi follows this text with an excerpt from the melodic material of 'Her Temple' in the piano interlude before an arpeggiated tonic chord greets the counterpoint once more, creating a frame of reference regarding the lost love (musical Example 16)."

(Denning, 70)

"Example 16: Transformations, Measures 30-32." (Denning, 71) |

"The last stanza relates Hardy's text triumphantly. Hardy proclaims the existence of our departed loved ones in the vibrancy of life around us, and Finzi reacts with a vocal line that is both high in pitch and dramatic in intensity, possessing a thickened accompaniment and a mediant to tonic cadence in our new key of D-major. This is a most effective ending which requires the singer to be reserved in order to avoid being caught up in the drive of the accompaniment, and to maintain control."

(Denning, 71)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Transformations by Carl Stanton Rogers. Permission to post this excerpt was extended by Dr. Rogers' widow, Mrs. Carl Rogers on March 1st, 2011. Dr. Rogers' thesis dated August 1960, is entitled:

A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page fifty-six and concludes on page sixty of the thesis. (Rogers, 56-60)

Part II, Number 4

"Transformations"

Two general features of this song are:

(a) The text setting is syllabic throughout.

(b) It consists of three stanzas; it is through-composed; therefore, its form is A B C.

The mood of this poem is reflected throughout in the music. Before beginning a discussion of the musical setting, it should be pointed out that the poem centers around the idea that all living things, and indeed all organic matter, are subject to an unremitting process of change and transformation from one state of existence into another. The first line of the poetry, "Portion of this yew is a man my grandsire knew," sums up this idea of the instability of all forms of life. This instability and constant change is enhanced musically by the use of restless and agitated rhythmic figures throughout the entire song. The song, therefore, is quite contrapuntal. The essential unity and yet the inexhaustible variety of all living things is also reflected in the unity and variety of the motivic fragments occurring throughout the piano accompaniment. The feeling of unity in the music is engendered by the intermittent exact repetition of several of the motivic figures, and yet variety too is achieved by varying slightly the intervals found in the motives from time to time. A short motive is stated in the first measure of the piano accompaniment. This original motive is not only repeated exactly several times during the song, but it is also used in at least five other somewhat different and varied forms in the piano accompaniment. Figure 34 shows the original motive and, also, the five variant motives derived from it. The original motive as it appears in Figure 34 will be signified, for the purpose of discussion, by the letter "M"; and the five variant motives, respectively, will be signified by the letters "M¹," "M²," "M³," "M⁴," and "M⁵." The variant motives are numbered according to their degree of approximation to the original motive. The beginning of the original motive, as well as that of each of the variant motives, is characterized by the upward leap of a fifth. The only exception to this rule is the fifth variant (M⁵) which, however, does contain several leaps of the fourth.

Fig. 34 -- "Transformations," original motive and five variant motives occurring in piano accompaniment.

The original motive and its varied forms are each not only repeated exactly at least once, but are also subtly used and combined simultaneously. Table VIII demonstrates this point. The table shows each measure in which the original motive, and any of the five variant motives, occurs, either singly or in combination.

TABLE VIII

USE OF ORIGINAL MOTIVE AND FIVE VARIANT MOTIVES

OF "TRANSFORMATIONS"

Measure

|

Motive

|

|

1 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M, M⁴ |

2 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M³, M⁴ |

6 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M |

7 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M |

8 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M¹ |

9 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M¹, M⁴ |

11 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M², M⁵ |

33 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M, M⁴ |

34 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M³, M⁴ |

36 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M, M⁴ |

37 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M¹, M⁴ |

39 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M², M⁵ |

40 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M⁴, M⁵ |

41 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

M⁵ |

Strict imitation is also used in this song, as shown in Figure 35. Here the motive which is stated in the highest voice of the piano accompaniment is imitated an octave below in a lower voice of the accompaniment.

Fig. 35 -- "Transformations," measures 3, 4, 5, use of strict imitation in piano accompaniment.

The preceding was an analysis of Transformations by Carl Stanton Rogers. Permission to post this excerpt was extended by Dr. Rogers' widow, Mrs. Carl Rogers on March 1st, 2011. Dr. Rogers' thesis dated August 1960, is entitled:

A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas HardyThis excerpt began on page fifty-six and concluded on page sixty of the thesis.

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Transformations by Michael R. Bray. Dr. Bray extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on March 19th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1975, is entitled:

An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

This excerpt begins on page fifty-eight and concludes on page sixty-three of the thesis.

(Bray, 58-63)

TRANSFORMATIONS

|

||

|---|---|---|

PORTION of this yew |

||

Is a man my grandsire knew, |

||

Bosomed here at its foot: |

||

This branch may be his wife, |

||

A ruddy human life |

||

Now turned to a green shoot. |

||

These grasses must be made |

||

Of her who often prayed, |

||

Last century, for repose; |

||

And the fair girl long ago |

||

Whom I often tried to know |

||

May be entering this rose. |

||

So, they are not underground, |

||

But as nerves and veins abound |

||

In the growths of upper air, |

||

And they feel the sun and rain, |

||

And the energy again |

||

That made them what they were! |

||

"Transformations" in the manuscript show "In a Churchyard" as an earlier title. Hardy identified the scene as Stinsford Churchyard. (Purdy, 198) Stinsford Church is about a mile and a half northeast of Dorchester.

The concept (or religious philosophy as it were) of the poem is a very old one seen most often as reincarnation in Hinduistic religion (in plant-life form here).

Besides this imaginative concept, Hardy had read such scientific essays as T. H. Huxley's The Physical Basis of Life which says that animal life may live in other forms only by feeding upon protoplasm that has lived, but died. In this scientific law, 'there is a sort of continuance of life after death in the change of the vital animal principle, where the body feeds the tree or the flower that grows from the mound.' " (Ransome, 169-193)

The "fair girl long ago / Whom I often tried to know" is evidently Louisa Harding, the daughter of a rich farmer in Stinsford, about a year younger than Hardy and, when he was a boy, socially superior. (Bailey, 375)

Like many of his poems, "Transformations" begins with distinct descriptive images and then closes with a conclusion or more generalized overview of the mood presented. As Hardy describes the "nerves and veins" that "abound in the growths of upper air" and "the energy again / That made them what they were," the surgence of reincarnated energies lifts the poem to an exhalted level.

The entire song, upon total examination, is a transformation itself. The beginning accompaniment embarks on what is to be the necessary element for transformation - active motion. This motive is comprised of two if not four sixteenth notes per quarter note beat moving in arpeggiated segments and scalewise in thirds and sixths. These figures first start in the very low registers of the piano rendering a muddy nondescript sound. As we shall later see, the range expands to its full extent only in the final five measures.

These opening motives are also the melodic motives. The melodic line, too, is filled with moving sixteenth. The patterns allow movement (transformation) to be faster and less inhibited both in rhythm and interval. And, as everything in the world is balanced to the effect that differences allow and define differentiation, Finzi stops all motion in order to give full impact to the transformations that are occurring in both text and accompaniment. Further in the

EXAMPLE 20: "Transformations" measures 9-11.

first verse, he pictures "A ruddy human life. . . " with a trill an d lone accented sixteenth note block chord giving an almost march-like effect. A lone trill low in the left hand begins the second verse providing a clean break.

The accompaniment throughout the second verse is very depictive of the grass on which Hardy must have been trodding in the Stinsford Church graveyard. The accompaniment creates a wavy grass texture by the syncopated rhythms in notes that constantly move scalewise within the interval of a sixth. In speaking of the grass as being "made / Of her

EXAMPLE 21: "Transformations" measures 18-19.

who often prayed, Last century, for repose," Hardy strikes a profound similarity to "Song of Myself" Part VI by Walt Whitman. Whitman says of the grass:

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.

It may be you transpire from the breasts of young men,

It may be if I had known them I would have loved them,

It may be you are from old people, or from offspring taken soon out of their mothers' laps.

And here you are the mothers' laps.

He further states:

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death . . . "

(Whitman, 28)

Since "Song of Myself" was not published within Leaves of Grass until 1861-2, it is conceivable that during those intense period of reading in London in the 1860's, Hardy may have read Whitman's poems.

To realize the repose for which she "prayed, Last century," Finzi adds only expressive marks. he slows the tempo down (poco ritardando), diminuendos the phrase, reduces the activity (pochissimo meno mosso - little less activity), and asks for the section to be played and sung sweetly (dolce). This change also preludes a reminiscent thought of "the fair girl long ago / Whom I often tried to know . . . " In reminiscent fashion Finzi reduces activity in the accompaniment so as to heighten the text. however, as soon as the thought of transformations reinstated in the entering of "this rose," the sixteenth note motion resumes. Perhaps the most overwhelming transformation of all follows this phrase.

Compare the opening measures of "Her Temple" (Example 9) with the following

EXAMPLE 22: "Transformations" measures 29-31.

They are alike. Contrary to a previously mentioned theory, Finzi's inclusion of the opening bars of "Her Temple" either draws a comparison between the woman in each poem - his wife, Emma Gifford - or a similarity in moods - that this persons memory or physical body be not lost in obscurity. The motion her again stops reinforcing the nature of transformation itself.

The accompaniment hurries off in sixteenth note motion to be checked but once more before the transformation is complete. In perspective, the poem thus far has been particular examples of this recycled energy theory of man. The third verse, then, processes the examples and concludes that "they are not underground, / But . . . abound / In the growths of upper air, . . . " This parallels Whitman's thoughts that life cannot die, but reappears even in "the smallest sprout." This reincarnation is physically felt with the constancy of the sixteenth note motion, the regularity of parallel thirds and sixths, the addition of more notes per chord, and the gradual ascension of the pitch to the very last note. And thus, the transformation is complete.

The preceding was an analysis of Transformations by Michael R. Bray. Dr. Bray extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on March 19th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1975, is entitled:

An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

This excerpt began on page fifty-eight and concluded on page sixty-three of the thesis.

(Bray, 58-63)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Transformations by John Keston. Mr. Keston extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on September 30th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1981, is entitled:

Two Gentlemen from Wessex: The relationship of Thomas Hardy’s poetry to Gerald Finzi’s music.

This excerpt begins on page one hundred three and concludes on page one hundred ten of the thesis. To view Mr. Keston's Methodology please refer to: Methodology - Keston.

TRANSFORMATIONS

|

||

|---|---|---|

PORTION of this yew |

||

Is a man my grandsire knew, |

||

Bosomed here at its foot: |

||

This branch may be his wife, |

||

A ruddy human life |

||

Now turned to a green shoot. |

||

These grasses must be made |

||

Of her who often prayed, |

||

Last century, for repose; |

||

And the fair girl long ago |

||

Whom I often tried to know |

||

May be entering this rose. |

||

So, they are not underground, |

||

But as nerves and veins abound |

||

In the growths of upper air, |

||

And they feel the sun and rain, |

||

And the energy again |

||

That made them what they were! |

||

POETIC METER

Hardy uses rhythmic variations in "Transformations," but the dominant pulsation appears to be trimeter, three feet, in all eighteen lines of this three stanza poem. The variations are so numerous as to be tedious reading for the layman or student and it si sufficient to say that after the first line of the first three stanzas which are trochaic trimeter, Hardy reverts to iambic trimeter with the free use of anapests.

RHYTHMIC RELATIONSHIP

Despite the rhythmic variations of "Transformations," Finzi has kept this song in duple two four meter. The complexity of changing from trochaic to iambic meter and dealing rhythmically with anapests presents no problem for Finzi. After a five bar introduction, Finzi stresses the first word of the text "portion," a trochaic pulse with a quarter note tied over to a sixteenth in the next bar. "Yew" is the next word stressed by Finzi in similar fashion. The anapest of "is a man" is dealt with as follows: "is a" receives two sixteenth notes and "man" a dotted eighth note. The third line of this first stanza has been set by Finzi appearing as though it comprised two anapests only. Being the last line of trochee pulses of which there are three - "bosomed here at its foot" - Finzi has used for the six syllables two sixteenths, a quarter, tow sixteenth notes in bar number ten, and a quarter note for the word "foot" in the eleventh bar. This pulsation of two sixteenths, a quarter, two sixteenths, and another quarter note would connote two anapests, but since the first sixteenth note begins bar number ten, it receives the musical stress, being the downbeat of that bar, thereby maintaining the trochee. In the transition now from trochaic to iambic meter still within the first stanza, Finzi reverses the pulses in this fourth line immediately by giving the first word "this" an eighth note only and stressing the next word "branch" with an eighth tied to a sixteenth. Finzi continues to deal with the rhythmic variations of this song expertly for the remaining stanzas.

TRANSLATION

"Transformations" needs no explanation except perhaps to affirm that the "yew" is a coniferous bush or tree often found in English country churchyards.

LIFE AFTER DEATH

In the original manuscript "Transformations" appeared as "in a Churchyard" identified by Hardy as Stinsford Churchyard. (Bailey, 375)