I look into my glass

- Musical Analysis Section

- Audio Recordings Section

- Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

- Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

- Mark Carlisle - Gerald Finzi: A performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and

- Leslie Alan Denning - A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

Poet: Thomas Hardy

Date of poem: (undated)

Publication date: The last poem in the collection: Wessex Poems (1898)

Publisher: Macmillan Publishing Company

Collection: Wessex Poems (1898)

History of Poem: James Osler Bailey writes: " 'I look into my glass' fittingly closes Wessex Poems, which opens with 'The Temporary the All,' expressing the illusions of Hardy's 'flowering youthtime.' 'I Look Into My Glass' asserts the 'throbbings of noontide' beneath the 'wasting skin' of a man nearly sixty." (Bailey, 110-1)

Poem

| 1 | I look into my glass, | a |

| 2 | And view my wasting skin, | b |

| 3 | And say, ‘Would God it came to pass | a |

| 4 | My heart had shrunk as thin!’ | b |

| 5 | For then, I, undistrest | c |

| 6 | By hearts grown cold to me, | d |

| 7 | Could lonely wait my endless rest | c |

| 8 | With equanimity. | d |

| 9 | But Time, to make me grieve, | e |

| 10 | Part steals, lets part abide; | f |

| 11 | And shakes this fragile frame at eve | e |

| 12 | With throbbings of noontide. | f |

(Hardy, 81) |

||

Content/Meaning of the Poem:

1st stanza: I look at my reflection in the glass and see a face wrinkled and old, I ask God: 'Would it be possible to toughen my heart as my features have been.'

2nd stanza: If this was granted, then I would not concern myself with those that no longer care for me, I would be composed while waiting out my last years.

3rd stanza: But time has softened my heart, my youth has been stolen, yet I remain, my shell continues to decay as I grow closer to my last days, even still, my heart beats like a young man's.

For additional comments as to possible meaning of the text please refer to: Content - Van der Watt.

Speaker: The speaker is Thomas Hardy. James Osler Bailey includes in his commentary about the poem a description of Thomas Hardy made by Henry Nevinson: "A pen-portrait by Henry Nevinson, drawn on May 30, 1903, shows what distressed Hardy when he looked into his glass: "Face a peculiar grey-white like an invalid's or one soon to die; with many scattered red marks under the skin, and much wrinkled - sad wrinkles, thoughtful and pathetic, but none of power or rage or active courage. Eyes bluish grey and growing a little white with age, eyebrows and moustached half light brown, half grey. Head nearly bald on the top, but fringed with thin and soft light hair. The whole face giving a look of soft bonelessness, like an ageing woman. Figure spare and straight; hands very white and soft and loose-skinned." (Nevinson, 807-8) as quoted by (Bailey, 111) "Hardy's pen-portrait offers fewer particulars but more deductions and his typical protest against the ravages of time. "I look in the glass. Am conscious of the humiliating sorriness of my earthly tabernacle, and of the sad fact that the best of parents could do no better for me. . . Why should a man's mind have been thrown into such close, sad, sensational, inexplicable relations with such a precarious object as his own body!" (Florence Hardy, Later Years, 13-4) as quoted by (Bailey, 111) Bailey goes on to say after quoting from Later Years: "His protests sprang from his feeling young inside, where his sensitivity to beauty and to pain still thrilled and shocked him. In the images of his memory, Time stood still. When, after Emma's death, he visited Sturminster Newton, he was amazed at the size of the monkey-puzzle tree he had planted: "He waited a moment as if thinking. Then: 'I suppose that was a long time ago. I brought my first wife here after our honeymoon. . . She had long golden hair. . . How that tree has grown? But that was in 1876. . . How it has changed. . .' He paused, still staring at the tree - then remarked: 'Time changes everything except something within us which is always surprised by change.' "

(Flower, 97) as quoted by (Bailey, 111)

Setting: Gazing into one's reflection.

Purpose: A reminder that regretfully we grow old and with age we seem even more susceptible to emotions.

Idea or theme: Getting older.

Style: Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt writes in his dissertation: "The poem is in a philosophical, introspective mood in the style of a monologue or soliloquy, sufficiently dramatic to be the latter." (Van der Watt, 385)

Form: James Osler Bailey writes: " "I Look into My Glass" is written in the stanza and meter of "short-metre doxology" of Hardy's copy of Hymns Ancient and Modern." (Bailey, 112 Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt writes in his dissertation: "The poem consists of three quatrains with lines of uneven length. The rhyme scheme is rounded: abab cdcd efef and the metre is largely iambic (l. 8 and 12 contain slight irregularities). The placing of the words "eve" and "noontide" at the end of lines 11 and 12 respectively, provides an effective visual contrast." (Van der Watt, 385)

Synthesis: The poem from the outset seems steeped in regret and self pity and to a certain degree this description is fitting but when we consider the mitigating circumstances, sympathy seems appropriate for the speaker. Hardy was approximately fifty-two years old when he wrote the poem, he was having difficulty coming to grips with his body growing older but at the same time having a youthful mind and zeal for life. To compound matters, his first wife, Emma had become more and more distant. Mark Carlisle writes, "Hardy's marriage to Emma had grown increasingly strained during the 1890's, and he began to spend less and less time with her. As a result, her resentment increased, and eventually it was clear that she had, in fact, 'grown cold' to him." (Carlisle, 52) Martin Seymour-Smith writes in his biography of Hardy: the poem may be the result of several terrible events in Hardy's life: the death of his father; a fire at his boyhood home in Stinford; the death of Tennyson, for whom Hardy had great respect; a visit to Fawley which he had hoped would lift his spirits but had the opposite effect because all Hardy could see was loss and death. (Seymour-Smith, 458-61) Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt writes in his dissertation that to write this poem may be another example of Hardy's bravery in that he was really discussing a taboo subject for most men, male menopause: "The poem is a courageous and honest attempt to verbalise the private horrors of the male menopause. With typical acuteness Hardy does not shirk from the unpleasant or embarrassing truths of his own troubled existence." (Van der Watt, 384-5)The poem is a mere twelve lines and three stanzas but within this short poem there is a plethora of ideas, and opinions as to what Hardy really was talking about. There is little wonder why Gerald Finzi chose to set a poem that invokes such thought provoking emotion.

Published comments about the poem: James Osler Bailey suggests a comparison of the poem to Hardy's The Well-Beloved and more specifically to the character in the story, Pierston: "The poem laments that his heart has not shrunk as his features have. Hardy was as sensitive to pain as to beauty, and in the 1890's, it seemed to him, Emma had "grown cold" toward his dreams, his ideas (as in Jude), and himself. The constantly abrasive pain of loneliness muted every joy. That his distress at remaining young in heart while growing old in body was more than a fleeting fancy is suggested in the The Well-Beloved. There Pierston's meditations upon this theme parallel the poem: "When was it to end - this curse of his heart not ageing while his frame moved naturally onward? Perhaps only with life." Pierston sees the fact in his glass: "The person he appeared was too grievously far, chronologically, in advance of the person he felt himself to be. . . Never had he seemed so aged by a score of years as he was represented in the glass in that cold grey morning light. While his soul was what it was, why should he have been encumbered with that withering carcase, without the ability to shift it off for another. . . ?" In this novel Hardy fulfils the wish of his poem: "Would God it came to pass / My heart had shrunk as thin!" After an illness, Pierston loses his sensitivity to beauty, the source of his inspiration as artist, and in the loss finds "equanimity": "The artistic sense had left him, and he could no longer attach a definite sentiment to images of beauty recalled from the past. . . 'I don't regret it. That fever has killed a faculty which has, after all, brought me my greatest sorrows, if a few little pleasures. . . Yes. Thank Heaven I am old at last. The curse is removed.' "

(Hardy, The Well-Beloved, Part II, Chapter XII, and Part III, Chapters IV and VII)

(Bailey, 111-2)

F. B. Pinion recorded the following comments in his commentary about Hardy's poem I Look Into My Glass: "Much personal experience, which will be revealed in later poems (e.g. 'In Tenebris', 'Wessex Heights'), lies behind this brief lyric. The poet's feelings are just as strong as ever though he appears to be ageing. Hardy had in mind the criticisms and disapproval evoked by Jude the Obscure, matrimonial tensions at home, the love he had felt for Mrs Henniker. . . All this is subsumed in the Time theme with which Wessex Poems opened. Perhaps the poem was written when Hardy revised the serial form of The Well-Beloved for book publication in March 1897. The hero reflects (ii.xii): 'When was it to end - this curse of his heart not ageing while his frame moved naturally onward?' Again (III.iv), 'never had he seemed so aged . . . as he was represented in the glass in that cold grey morning light. While his soul was what it was, why should he have been encumbered with that withering carcase . . .?'" (Pinion, 27-8)

Martin Seymour-Smith comments on the poem and others that have analyzed it in the past with: "So powerfully do the majority of Hardy's critics resist this as a poem making a universal statement about how both men and women feel about ageing that they invent all kinds of special occasions for it, all more or less subtly derogatory of its author. Bailey is sure that Tom felt especially bad about his own features, and Millgate, unable to imagine any man's general feeling of dissatisfaction with so splendid a thing as even his fifty-two-year-old body (male, after all), invents a specific sexual rebuff. The sixth line of the poem is usually connected with Tom's awareness of Emma's specific hostility, but its sense, surely, is that human beings do not often feel romantic love for older, wrinkled specimens. The poem may quite as well be read in a woman's as in a man's voice, although the latter, too, runs against the grain of the Victorian sensibility, which held - even in the teeth of the evidence - that women were the spotless receptacles of masculine impurity, themselves 'untroubled' by sexual feelings."

(Seymour-Smith, 461-2)

Criticism: Kenneth Marsden writes in response to the poem: "The linguistic variation here is no greater than is to be expected among good poems; it is, in fact, one of the few successful Hardy poems which could be by someone else. (There is a resemblance to Yeats, whose Song, 'I thought no more was needed', might almost be an answer to it, since it takes the opposite side in the Body/Soul conflict.)" (Marsden, 164-5)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

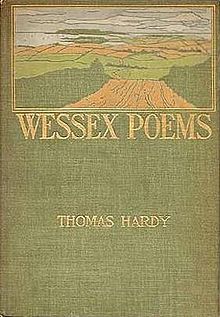

Wessex Poems

- Collection of 51 poems written by Thomas Hardy.

- Published in December of 1898 by Harper and Brothers.

- Hardy's first publication of his poems.

- Contains 30 illustrations made by Hardy.

F. B. Pinion categorizes the poems as a miscellaneous collection; ranging from ones strongly narrative to those that display Hardy's connection to Wessex. There are also poems that show Hardy's affinity for the Napoleonic War. (Pinion, 3)

"An anonymous reviewer for the Athenaeum believed the most successful poems were those that concentrated on Hardy's 'curious intense and somewhat dismal view of life.'" (Wright, 346)

"W. M. Payne, writing in the Dial, declared that the poems displayed 'much rugged strength and an occasional flash of beauty.' He believed there were several that almost persuaded him 'a true poet was lost when Mr. Hardy became a novelist.'" (Wright, 346)

Gerald Finzi set the following poems within this collection:

- Amabel (Before and After Summer)

- Ditty (A Young Man's Exhortation)

- I Look Into My Glass ( Till Earth Outwears)

- The Sergeant's Song [titled by Finzi as: Rollicum-Rorum] (Earth and Air and Rain)

Helpful Links:

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Musical Analysis

Composition date: 1930's (McVeagh, 81)

Publication date: © Copyright © 1958 by Boosey & Co. Ltd.

Publisher: Boosey & Hawkes - distributed by Hal Leonard Corporation

Tonality: The song begins in G Major and ends in G minor but in between Finzi flirts with D minor without firmly establishing the key. The lack of a dominant chord after measure six creates tonal ambiguity for the remainder of the song. And, even though there is no dominant to tonic chords, Finzi uses a neapolitan chord with a minor seventh built on E-flat in measure twelve in an attempt to commit to D minor. The neapolitan chord, is soon replaced with an increased use of chromaticism and seventh chords some of which are augmented (see example below).

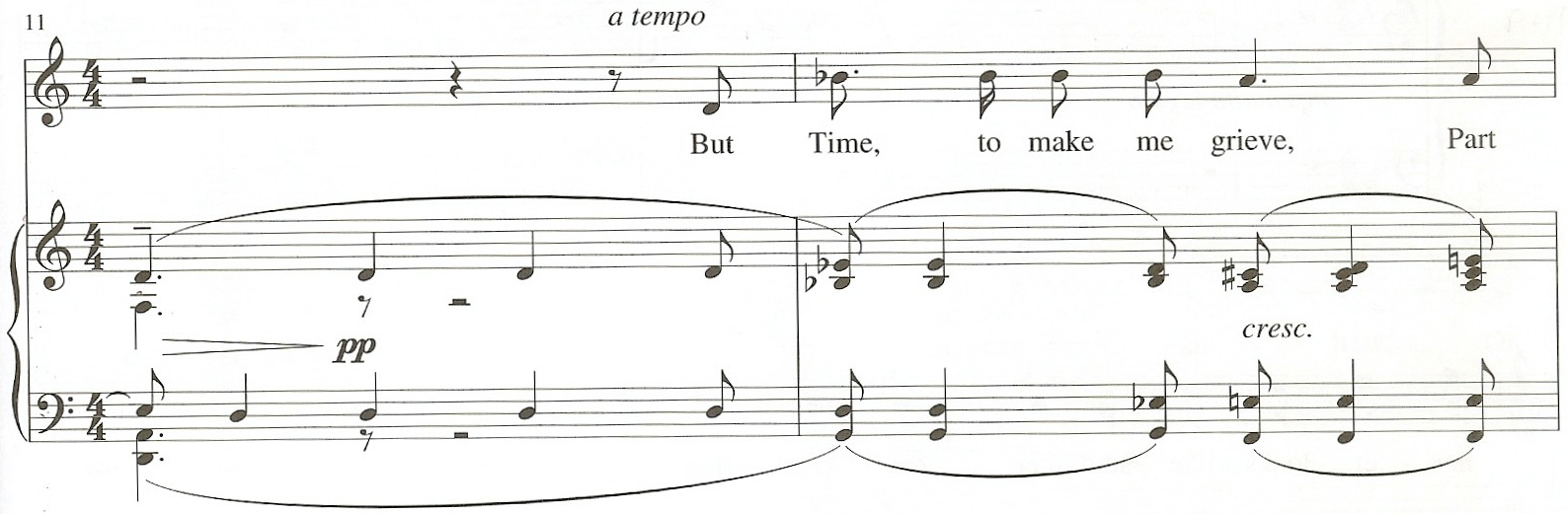

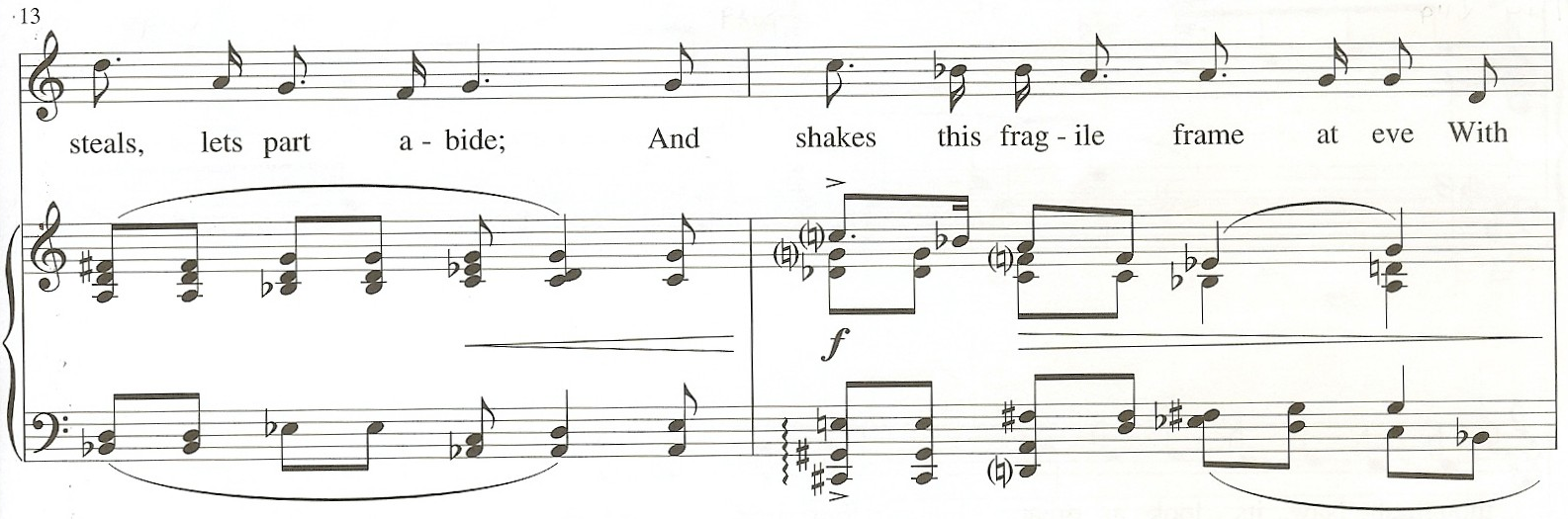

Neapolitan and increased use of dissonance in measures 11-4. (Finzi, 97)

Finzi's use of chromaticism lessens by the beginning of measure fifteen when G minor begins to creep in. By the middle of the measure, with the inclusion of B-flat, G minor is present but in order to continue the harmonic tension in support of the text, Finzi has written in the bass a major third built on A-flat. The dissonance finally gives way in measure sixteen as the A-flat and C expands to a perfect fifth built on G. G minor is established without ever using a dominant chord, instead Finzi has relied on dissonance resolving to consonance to create a sense of cadence and G minor (see example below).

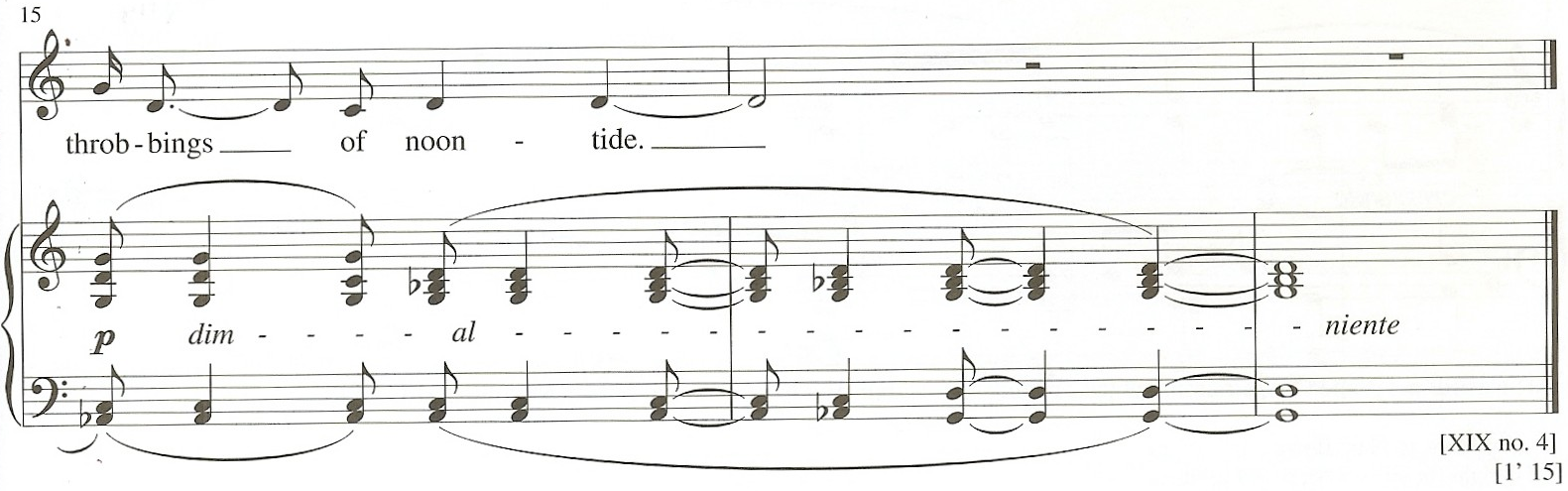

Dissonance gives way to consonance in measures 15-7. (Finzi, 97)

For additional information about the original key please refer to: Tonality - Van der Watt.

Transposition: The song is available a minor third lower than the original key. The transposed version may be found in the Medium/Low Voice edition by Boosey & Hawkes entitled: Gerald Finzi Collected Songs 54 Songs Including 8 Cycles or Sets.

Duration: Approximately two minutes and five seconds.

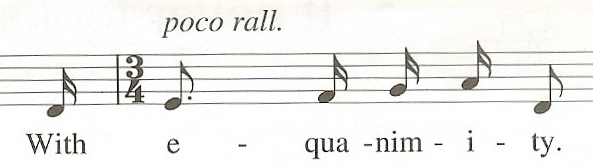

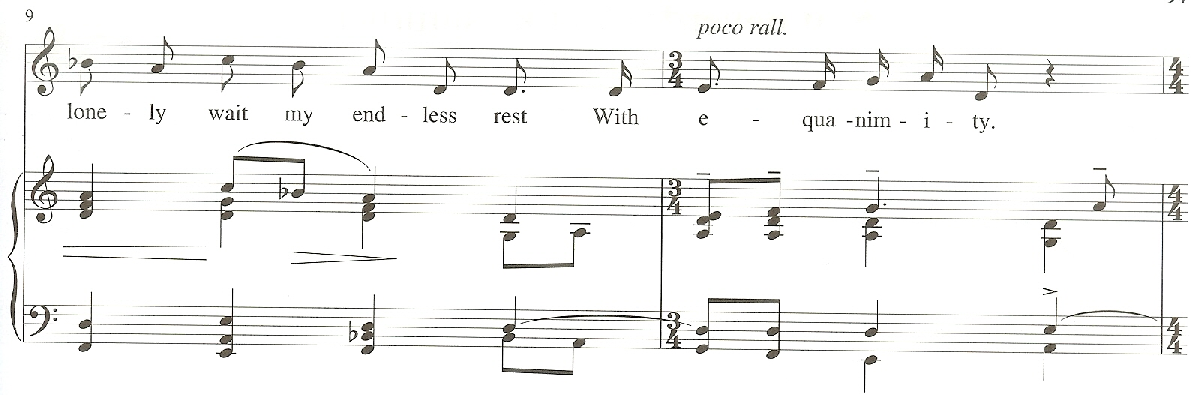

Meter: Measure ten is in 3/4 otherwise the entire song is written in 4/4. For additional information about the meter please refer to: Metre - Van der Watt.

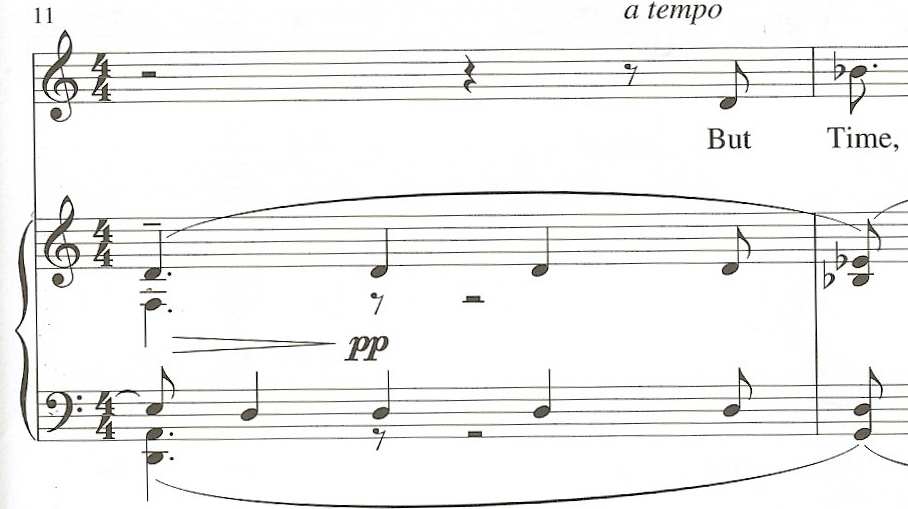

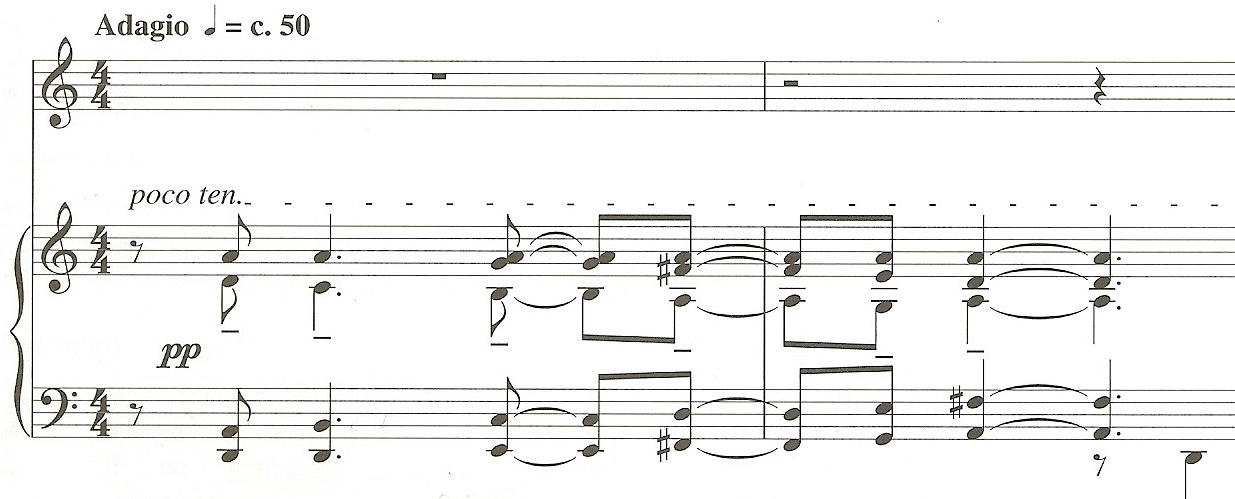

Tempo: The opening indication is Adagio with the quarter note equalling c. 50. There is a single deviation occurring in measure ten with poco rallentando indicated. By the end of measure eleven a tempo is indicated. For additional comments about the tempi please refer to: Speed - Van der Watt.

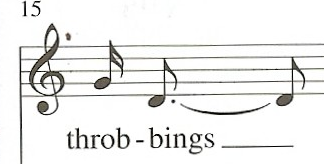

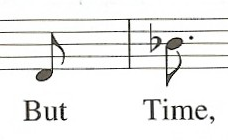

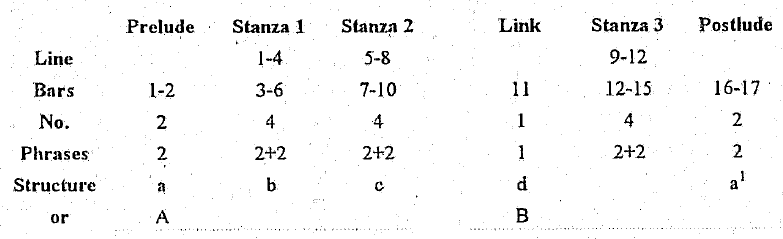

Form: The song is through-composed but can be divided into two sections. The B section beginning with the third beat in measure ten as the interlude material begins (see example below).

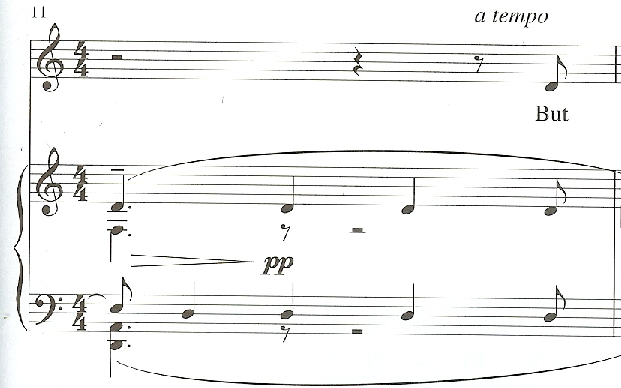

Interlude between stanzas two and three in measures 10-1. (Finzi,97)

The interlude material is reminiscent of the opening prelude and postlude primarily because of rhythm and emphasis of the off-beat (see prelude and postlude below).

Prelude in measures 1-2. (Finzi, 96)

Postlude in measures 15-7. (Finzi, 97)

The piano accompaniment in the prelude, interlude, and postlude serve as unifying material for the song but the vocal lines are completely through-composed.

For additional information about the specific sections of the song and other information about the form please refer to: Structure - Van der Watt.

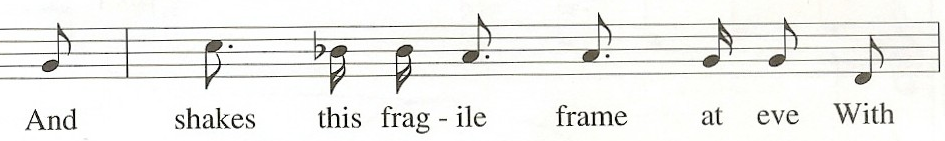

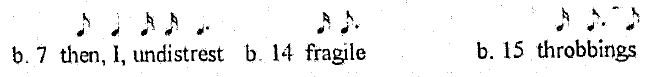

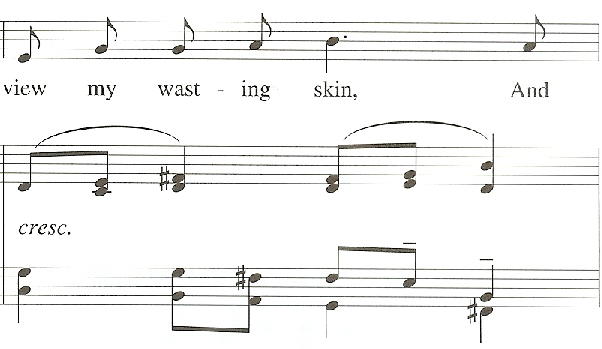

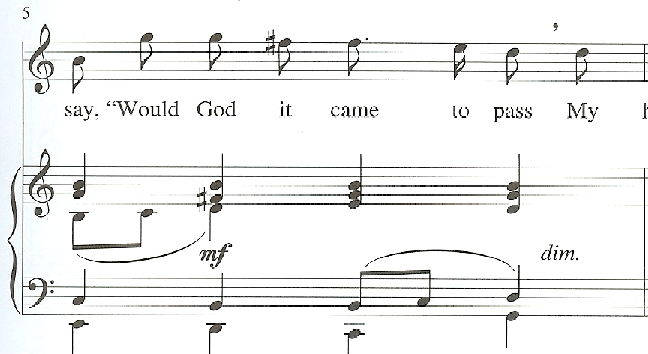

Rhythm: As was mentioned in the above section, Form, the use of rhythm and more particularly the emphasis of the off-beat gives some unity and therefore serves an important role in the song. The vocal line has typical rhythms for Finzi with the eighth note being used prominently. Finzi's text setting seems less on display in this song as more emphasis has shifted to harmonic tension but there are a couple of settings worthy of notice (see examples below).

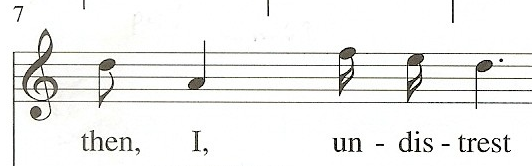

Text setting in measures 9-10. (Finzi, 97)

Text setting in measures 13-5. (Finzi, 97)

For additional information about the rhythm and the rhythmic motifs of the song please refer to: Rhythm - Van der Watt.

A rhythmic duration analysis was performed and for the results please refer to: Rhythm Analysis. Information contained within the analysis includes: the number of occurrences a specific rhythmic duration was used; the phrase in which it occurred; the total number of occurrences in the entire song.

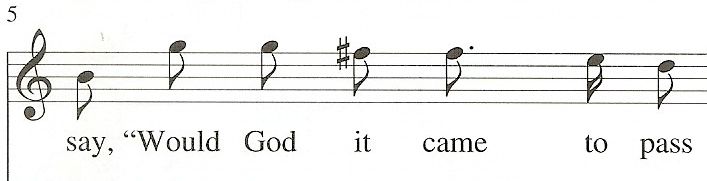

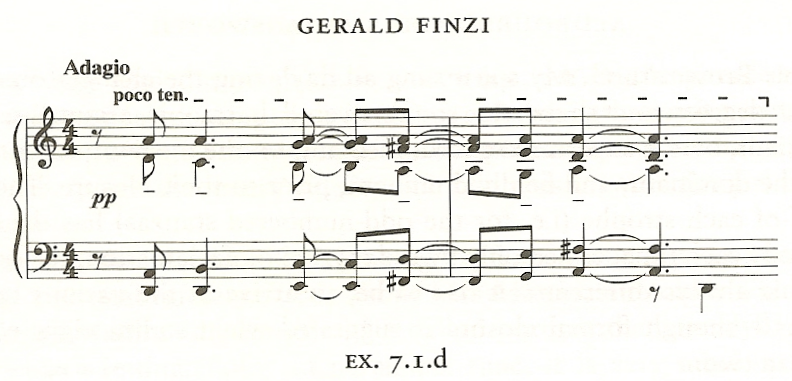

Melody: Melody is less prominent in this song than rhythm and harmonic tension. The vocal line is written in a typical manner for Finzi with step-wise motion and small leaps. Larger leaps are usually held in reserve for highlighting the text and dramatic emphasis. The ascending minor sixth is the largest leap in the vocal line and it is used three times. The first occurrence is in measure five and it is used as a plea to God; the second occurrence in measure seven emphasizes the word "undistrest" which means "without stress" and seems almost ironic or sarcastic with the large leap attached to it; the last occurrence between measure 11 and 12 coincides with the beginning of the third stanza of the text and is less dramatic because it occurs lower in the vocal range (see examples below).

Leap of a minor sixth in the vocal line in measure 5. (Finzi, 96)

Leap of a minor sixth in the vocal line in measure 7. (Finzi, 96)

Leap of a minor sixth in the vocal line between measures 11-2. (Finzi, 97)

For additional information about the melodic material within the song please refer to: Melody - Van der Watt.

An interval analysis was performed for the purpose of discovering the number of occurrences specific intervals were used and also to see the similarities if there were any between stanzas. Only intervals larger than a major second were accounted for in the interval analysis. For a complete description of the results of the interval analysis please see the table at the bottom of the page or click on: Interval Analysis.

Texture: The texture is homophonic and even in the more dissonant last stanza the vocal line is well supported. For a brief description about the texture including a table outlining the types of texture and the percentage in which they were used please refer to: Texture - Van der Watt.

Vocal Range: The vocal range spans an interval of a perfect twelfth. The lowest pitch is the C below middle C and the highest pitch is the G above middle C.

Tessitura: The tessitura spans one octave from the D below middle C to the D above middle C. A pitch analysis was performed for the purpose of accurately determining the tessitura and for the complete results please refer to: Pitch Analysis.

Dynamic Range: The dynamics span the distance between piano and forte, with the louder dynamics being reserved for the most dramatic moments of the song in measures five with mezzo-forte indicated and then in measure fourteen with forte indicated. There are no separate indications of dynamics for the vocal line therefore one may assume, because of Finzi's common practice, that the voice should observe the dynamics indicated for the piano accompaniment. For additional comments about dynamics including a table listing where each dynamic is indicated within each stanza please refer to: Dynamics - Van der Watt.

Accompaniment: The creation of atmosphere is very important in this song and Mark Carlisle has commented in his dissertation that, "the poetry of this song reflects considerable internal resentment and animosity toward life, so performers should keep this emotional "heaviness" in mind while working within the confines of an essentially introverted musical response." (Carlisle, 56) Dr. Carlisle goes on to make some suggestions for tempi in his "Comments about Performance" section within his dissertation: "Tempo in particular should be gauged to most effectively reproduce this sensation, without permitting musical stagnation to intervene. The opening tempo marking of [quarter note] = c. 50 (Adagio) is generally appropriate, but more flexibility should be allowed throughout the song than is indicated by the only two other expressive markings, poco rallentando in measure 10, and a tempo in measure 11. Measures 5-6 in particular would be better served by a slight reduction in tempo, if only to highlight the dramatic quality of the poetry at this moment. A poco rallentando should also be inserted at the end of measure 6, for this is clearly a phrasal point in the song. While tempo at the end of the song should remain relatively consistent, both performers would do well to use some slight rubato in measure 15 to underscore the great importance of the words, 'throbbings of noontide.' " (Carlisle, 56) To view Dr. Carlisle's suggestions for performance please refer to: Comments about Performance - Carlisle. For additional information about the accompaniment please refer to: Accompaniment - Van der Watt.

Published comments about the music: Diana McVeagh writes in her Finzi biography: "'I look into my glass' has a Wolfian intensity, as an ageing man scans his reflection, bitterly aware of the contrast between his old body and still ardent heart. In the piano part Finzi's repeated notes - A's and D's - suggest numbness; but they develop into pulsing chords, increasingly chromatic as passion 'shakes this fragile frame', before subsiding once more. The tenor cries out 'would God it came to pass' on the highest notes; and, having begun on a high D, ends on a low D. The song is packed, compressed, and powerful." (McVeagh, 81)

Stephen Banfield writes in his Finzi biography the following: "The first three lines of strophic ballad melody in 'Amabel' are found again in the first four-line stanza of 'I look into my glass', but the point here is to dislocate the ballad framework. This happens in two ways. Firstly, after a mediant caesura has been reached at the end of the first stanza (as so often, pointed up by staccato quavers in the piano), the second half of the quadratic melody, for stanza two, is presented a step lower than expected. This has the effect of concluding it not in the relative minor (E minor) but in D minor, which in an odd sort of way accords with the song's introduction and its presentation of the opening melody as mixolydian D rather than on the dominant of G major. Yet this apparent consequent, in the second gesture of dislocation, proves to be in itself the antecedent of the real one, the poem's third and final stanza. Here the throbbing D becomes a dominant once more, so that the song ends in G minor. The song as a whole, therefore, operates ambiguously between unified and 'progressive' tonality - a composed-out drop of a fifth - and between different modal interpretations of a basic d to d¹ melodic ambit, a multiple perspective that accords well with Hardy's poetic one, in this, the last and one of the finest of his Wessex Poems, of the apparent closure of old age being opened out again by the 'throbbings of noontide' in the 'fragile frame at eve'. It is quite likely that Finzi arrived perforce at this unorthodox whole by stitching together disparate sketches, but that would not invalidate the result. . . "'I look into my glass' is not only formally shrewd but expressively rewarding, its chromatically passionate harmonies at the one end foiled by the vainly dispassionate ones at the other, in neoclassical equipoise (for the image of the mirror) and with something of the sixth-, second- and seventh-based sonorities of Britten or Tippett (ex. 7.I.d)." (Banfield, 245)

Musical example 7.I.d. (Banfield, 246)

Pedagogical Considerations for Voice Students and Instructors: This song should present no problems for either the tenor in the high key or the baritone in the medium/low key with regards to range, although, measures five and seven may require some additional preparation. The leap in measure five can be a little difficult if one does not take an adequate breath before "and," at the end of measure four. It would be best to lightly articulate the text, "Would God it came," in measure five as well. The lighter articulation in combination with the good breath and support, should allow one to manage the phrase much easier. The leap to the text "undistrest" is made more difficult with the up and down motion of the vocal line that precedes it. One need observe the breath flow as the leap is negotiated. If one has a tendency to push the breath, place an [f] in front of the text "undistrest" and observe the results. It should also be noted that a glottal in front of "undistrest" is not wise. Finzi wrote two descending sixteenth notes on the first two syllables of "undistrest" leading one to emphasize the last syllable. This is good pedagogically as well because it directs the voice in a descending melody thus eliminating the emphasis on the high note and hopefully the stress.

Dr. Mark Carlisle records in his dissertation the following observations and advice: "There is little in this piece that should cause any serious technical difficulties for a tenor, although one with a very light voice might find some difficulty handling the demands of the lower tessitura at the end of the song. The highest note in the range is g¹, sung only briefly in measure 5, and the tessitura is the lowest of any song in this set. By far the most serious demands on the performer of this song are interpretive; an artistic rendering of the text requires that the performer be able to empathize with those who suffer the emotional effects of advancing age combined with decreasing physical facility. While this concept can no doubt be "interpreted" to some extent by even the most youthful performers, it seems appropriate to suggest that this piece is not well-suited for very young singers. It is not a difficult piece to "sing," but an insightful and rewarding performance really requires the interpretive skills found in singers at the graduate level and beyond." (Carlisle, 57-8)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Below one will find excerpts from unpublished dissertations. The excerpts should provide a more complete analysis of I look into my glass for those wishing to see additional detail. Please click on the link or scroll down.

Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

| Pitch Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pitch | stanza 1 |

stanza 2 |

stanza 3 |

total | |

highest |

G |

2 |

2 |

||

F |

2 |

1 |

3 |

||

E |

1 |

1 |

2 |

||

D |

3 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

|

middle C |

2 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

|

B |

5 |

5 |

6 |

16 |

|

A |

5 |

6 |

5 |

16 |

|

G |

3 |

2 |

6 |

11 |

|

F |

2 |

1 |

3 |

||

E |

2 |

1 |

3 |

||

D |

1 |

4 |

5 |

10 |

|

lowest |

C |

1 |

1 |

||

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Audio Recordings

The Songs of Gerald Finzi to Words by Thomas Hardy

|

|

|

|

Gerald Finzi Song Collections |

|

|

|

The English Song Series - 16 |

|

|

|

Song Cycles for Tenor & Piano by Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

Oh Fair to See: Songs by English composers |

|

|

|

Songs of the Heart: Song Cycles of Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

The following is a text analysis of Thomas Hardy's poem I look into my Glass by Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt. Dr. Van der Watt extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on October 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated November 1996, is entitled:

The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt comes from Volume II and begins on page three hundred eighty-four and concludes on page three hundred ninety-one. To view the methodology used within Dr. Van der Watt's dissertation please refer to: Methodology - Van der Watt.

1. Poet

Specific background concerning poem:

"The poem was first published in Wessex Poems (1898) and seems to have been written in October 1892, according to a note Hardy wrote to his first wife, Emma, at that time. James Gibson, in his introduction to the Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, says:"

(Van der Watt, 384)

"Thomas Hardy was fifty-eight and had already published fourteen novels and more than forty short stories when Wessex Poems, the first of his eight books of verse, was published in 1898." (Hardy, xxxv) as quoted by (Van der Watt, 384) |

"In connection with the subject matter of the poem Seymour-Smith says:"

(Van der Watt, 384)

"The neo-Victorian concept of a mature man as serene and untroubled by romantic emotion, is false. (Seymour-Smith, 403) as quoted by (Van der Watt, 384) |

"Thomas Hardy writes a note to Emma on 18 October 1892, which reads (quoted from Seymour-Smith):"

(Van der Watt, 384)

"Hurt my tooth at breakfast-time. I look in the glass. Am conscious of the humiliating sorriness of my earthly tabernacle, and of the sad fact that the best of parents could do no better for me . . . Why should a man's mind have to be thrown into such a close, sad sensational, inexplicable relation with such a precarious object as his own body?" (Seymour-Smith, 461) as quoted by (Van der Watt, 384) |

2. Poem

"The poet beholds his ageing features in the mirror. He invokes God to make his heart, the centre of human emotions, deteriorate at the same pace as his physical appearance. With such a shrunken emotional awareness, he would not be affected by people's indifference or rejection and he could await death in composed isolation. The poet knows, however, to his sorrow and disappointment, that his invocation is idle because the impulses of desire and emotion make his frail, physical outer-shell quiver, as he grows older. The poem is a courageous and honest attempt to verbalise the private horrors of the male menopause. With typical acuteness Hardy does not shirk from the unpleasant or embarrassing truths of his own troubled existence."

(Van der Watt, 384-5)

"The poem is in a philosophical, introspective mood in the style of a monologue or soliloquy, sufficiently dramatic to be the latter."

(Van der Watt, 385)

"The poem consists of three quatrains with lines of uneven length. The rhyme scheme is rounded: abab cdcd efef and the metre is largely iambic (l. 8 and 12 contain slight irregularities). The placing of the words "eve" and "noontide" at the end of lines 11 and 12 respectively, provides an effective visual contrast."

(Van der Watt, 385)

"The simple structure and style of the poem belies the emotional trauma which throbs underneath. The single image of an ageing man in front of a mirror, not in vain self-admiration but in a mood of introspective disillusionment, overshadows the entire poem. Seymour-Smith says of the poem:"

(Van der Watt, 385)

"Its melancholy was the result of recent blows: the death of his father; the fire at Stinford, which seemed to destroy all the memories of his youth just as his father had been destroyed by time, the departure of that poetic fixture, Tennyson, and the visit to Fawley. The poem is one of his most moving." (Seymour-Smith, 461) as quoted by (Van der Watt, 385) |

Setting

1. Timbre

VOICE TYPE/RANGE

"The song is set for tenor voice and range is a perfect twelfth from the first C below middle C."

(Van der Watt, 385)

"The upper limit used in the piano accompaniment is the first C above middle C and therefore forces the accompaniment into the middle and lower registers. This C occurs at the emotional climax of the song in bar 14 on the word "shakes" and is an appoggiatura against a bi-tonal construction: C sharp-E-G sharp + g-B flat-D flat. The lowest pitch used is the second C# below middle C (not extremely low either) and occurs at exactly the same moment as the highest pitch. The accompaniment therefore spans a range of just three octaves - a tight constraint on the part of the composer - and is directly linked to the privacy of the poem's content."

(Van der Watt, 385)

"There are no indications for the use of pedalling in the piano part although it will certainly be necessary in a very chordal and slow-moving context. Legato indications are not used, but this does not necessarily imply a non-legato touch. The atmosphere and material indicates that the playing should be legato except where otherwise specified (b. 6). There are a number of portamento accents (b. 1-2(6), 4(2), 6, 8, 10(4) and 11). The six indications in bars 1 - 2, are significant: the accents occur in the alto of the right hand part and accentuate a rhythmic augmentation of the opening melodic line - a five-note descending melodic motif with the words "I look into my glass" - and sets the melancholy, contemplative mood of the song from the very first instance. Two staccatos are used on bar 6³ with the word "thin". This ascending motif supports the text and the staccato thins out the sound. Stronger accents (>) are used in two bars. In bar 10 a single E (tenor of the piano part) is accented due to its suspension into the next bar against the tonic chord in d minor. This suspension and resolution is also a varied imitation of the immediately preceding melodic line (b. 10 "equanimity") which in outline, also moves from E to D, hence the accent. The other two accents occur on the emotional climax in bar 14 with a f dynamic indication and first of the only three, six-part chords used in the song. The drama of this particular moment is further enhanced by harsh dissonance used in the chordal construction. The accents intensify the effect of the elements collectively employed."

(Van der Watt, 385-6)

"The atmosphere to start with is more indifferent (b. 1-6) than melancholic. From the modulation to d minor, an almost relentless, tonal darkness sets in. This melancholy reaches despairing proportions in bar 14 and is not redeemed towards the end. The final cadence, a Neapolitan to Tonic movement, leaves the listener ill at ease and appeals for a sense of understanding if not pity."

(Van der Watt, 386)

2. Duration

"The textual metre is iambic and is matched with a common-time time-signature. A single bar (b. 10) deviates from this to a simple triple time-signature. The shortened bar reflects the shortest line in the poem (l. 8), "with equanimity"."

(Van der Watt, 386)

Rhythmic motifs

"Few rhythmic motifs establish themselves in the song. Motif 1, consisting of four quavers occurs 10 times (b. 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13(2) and 14(3)) in both vocal and piano parts and represents the basic, rhythmic movement. Motif 2, consisting of two quavers and a crotchet occurs nine times (b. 4(3), 5(2), 6, 7 and 10(2)) in the piano part only. This motif creates a sense of unity in the first half of the song. In the second half of the song motif 3, consisting of a quaver-crotchet-quaver occurs eight times (b. 12(4), 13(2) and 15(2)) in the piano part only. This motif in a varied guise appears also in the prelude and postlude and gives the impression of a "throbbing" and is therefore the most significant rhythmic feature of the song."

(Van der Watt, 386)

Rhythmic activity vs. Rhythmic stagnation

"The rhythmic movement is fairly uniform throughout the song. The prelude (b. 1-2) and postlude (b. 15³-17) have a slightly more hesitant rhythmic activity and have the throbbing character, as suggested earlier."

(Van der Watt, 386)

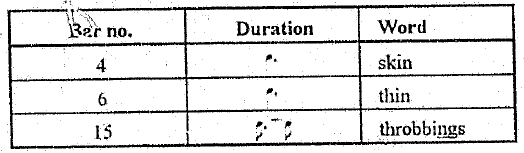

Rhythmically perceptive, erroneous and interesting settings

"The following words have been set to music perceptively:"

"The setting of the word "equanimity" could be criticized. The dotted quaver on the first syllable of the word, coinciding with the strongest beat of the bar, goes against the natural pronunciation which has the main accent on the third syllable. Although this happens on beat two, it should have been on a stronger beat that the first syllable. In a 4/4 bar the word should have started on beat two, the first syllable should only have been a quaver and the third syllable should have been on the third beat with a short value (as Finzi has done)."

(Van der Watt, 386)

Lengthening of voiced consonants

"The following words containing voiced consonants have been rhythmically prolonged in order to make the word more singable:"

(Van der Watt, 387)

"The tempo indication is Adagio [quarter note equals] c. 50. Tempo deviations are listed below:"

Bar no. |

Deviation |

Bar no. |

Return |

Suggested reason/s |

1¹ |

poco ten. |

2⁴ |

a tempo |

Hesitant, anticipate the meaning of the first line |

10 |

poco rall. |

11⁴ |

a tempo |

End of stanza 2, reference to death |

"The initial extended tenuto indication is an interesting and unconventional one and has a foreboding effect in the prelude."

(Van der Watt, 387)

3. Pitch

Intervals: Distance distribution

Interval |

Upwards |

Downwards |

Unison |

(17) |

|

Second |

14 |

23 |

Third |

4 |

2 |

Fourth |

3 |

6 |

Fifth |

1 |

3 |

Sixth |

3 |

0 |

"There are 17 repeated pitches (or 22% of the total number), 25 rising intervals (or 33%) and 34 falling intervals (or 45%). The smaller intervals (a third and smaller) account for 60 intervals (79% of the total number) while the larger intervals (fourths and larger) account for 16 (or 21%). The vocal intervals are significantly voice-friendly and the descending intervals in the vocal part are partly responsible for the sense of dejected melancholy which prevails in the song. A number of specific setting will be discussed below:"

Interval |

Bar no. |

Word/s |

Reason/s |

5th down |

3 |

glass And |

Change of register |

4th up |

5 |

say, "would" |

Emphasis, emotional content |

4th down 5th up |

6 |

shrunk as thin |

Reinforce emotional content |

6th up |

7 |

I, undistrest |

Emphasis |

5th down |

9 |

endless |

Reinforce emotional content |

5th down |

10 |

equanimity |

Reinforce emotional content |

6th up |

11-12 |

But Time |

Emphasis |

4th up 4th down |

12-3 |

Part steals |

Emphasis |

4th up |

13-4 |

and shakes |

Emphasis, emotional content |

5th up 5th down |

14-5 |

with throbbings |

Reinforce emotional content |

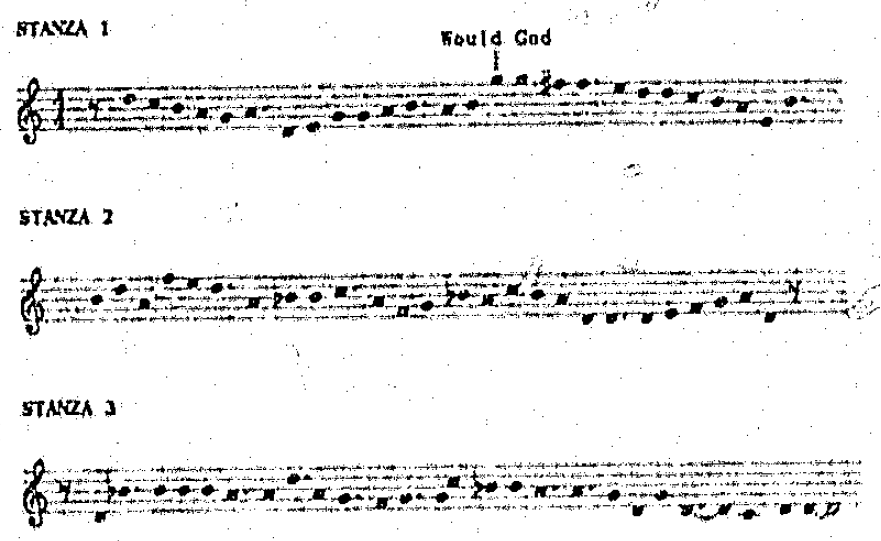

Melodic curve

A melodic curve of the vocal line is represented below. Certain wards are indicated to show the relationship between the melodic curve and the meaning:"

(Van der Watt, 388)

(Van der Watt, 388)

Climaxes

"There is a single vocal climax on G early in the song with the words "Would God". The invocation to have a better balance between physical and emotional deterioration is emphasized by the placing of this climax."

(Van der Watt, 388)

Phrase lengths

"The vocal phrases are long and only on one occasion has the composer indicated specifically where a breath should be taken (b. 5⁴). Here are additional suggestions for breathing places: bars 7⁴ or 8⁴and 13⁴."

(Van der Watt, 388)

TONALITY

"The song is in G major-minor (starting in G major and ending in g minor). All modulations are summarized below:"

Bar no. |

From - To |

Suggested reason/s |

7 |

G - d |

Text supported: "then, I, undistrest" (stanza 2) |

11 |

d - g |

Text supported: "to make me grieve" - darker mood |

Chromaticism

"Chromaticism is quite a significant feature of the song. All chromatic occurrences are summarized in the following table:"

Bar no. |

Beat |

Chromaticism |

Chord |

Word |

12 |

3 |

C sharp & E |

V/iv add min 6th |

grieve |

13 |

1 |

F sharp & C |

V and min 6th |

steals |

13 |

3 |

A flat |

Nap⁷ |

abide |

14 |

1 |

C sharp, G sharp, E, D flat |

C sharp-E-G sharp G-B flat-D flat |

shakes |

14 |

2 |

F |

D-F sharp-A +F-A-C |

fragile |

15 |

1-4 |

A flat |

Nap⁷ |

throbbings |

"The first matter of interest here is that the chromatic usage starts from bar 12 and intensifies towards the end, as the atmosphere becomes more despairing. This fact is a clear indication of Finzi's attitude towards chromaticism: it is reserved for emotionally troubled moments. Secondly, the chord consisting of a major triad with an additional minor sixth, is a novel construction used twice in bars 12 and 13. Thirdly, the Neapolitan triad, built on the lowered second step, is extended by the addition of a seventh. Finally, two sets of poly-tonal chords are used consecutively in bar 14. All these features serve to extend the dissonance and are associated not only with disdainful mood of the poet towards his own middle age crisis, but also with the crisis of ageing for all mankind and specifically the physical deterioration, which takes place far more quickly than the emotional and sensual decline."

(Van der Watt, 389)

HARMONY AND COUNTERPOINT

"Instances of chromaticism have been discussed, yet there are un-chromatic chord extensions which serve much the same purpose but on a less intense level. Some examples are:"

Bars |

1³-ii⁹, 3¹-V⁹, 4³-I⁷, 5³-IV⁷, 6¹-ii⁹, 9²-V⁹ and 10²-ii⁷ |

"These occur mainly in the first half of the song and the dissonance supports the general melancholy atmosphere."

(Van der Watt, 389)

Non-harmonic tones

"Suspensions play a significant role in the song and by their very nature create dissonance on the beat (b. 4¹(D), 4²(G), 7³(G), 8¹(A), 8³(A), 10¹(A), 11¹(E) and 15¹(D)). These mild dissonant moments enhance the general atmosphere of disillusionment."

(Van der Watt, 389)

Harmonic devices

"There is an A pedal note in the soprano of the piano part in bars 1 - 2 which creates harmonic tension in the prelude and serves as an anticipation of what is to follow. In the parallel postlude, a G-B flat-D chord is sustained over bars 15³ - 17. Here the function is different: in a dissonant context the minor tonic chord brings some sense of stability and acceptance of the inevitable."

(Van der Watt, 389)

Counterpoint

"There are two minute imitations between the vocal and piano parts: bar 7² voice - bar 4 piano and bar 10¹-³ voice - bar 10³-11² piano (simplified). There are similarly small, nevertheless noticeable, imitations in the piano part internally: bar 5¹-² alto - 5³-⁴ tenor, 9²-³ soprano - 9⁴-10¹ bass (varied). These cross-references brings about subtle unity within a fairly loose construction."

(Van der Watt, 389-90)

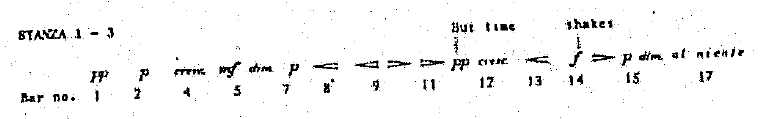

"Loudness variation is given in the following summary:"

(Van der Watt, 390)

(Van der Watt, 390)

FREQUENCY

"There are 18 indications in the 17 bars which means that on average each bar contains an indication. In reality some bars do not contain indications while others contain two or three. There are no separate indications for the voice which implies that the voice should follow the indications given in the piano part."

(Van der Watt, 390)

RANGE

"The lowest level indication is pp in bars 1 and 11, the prelude and the link between stanzas 2 and 3. The quiet beginning shows the sympathetic attitude of the composer towards the subject matter, and prepares the listener for the very private statement made in the poem. The loudest level indication is f and occurs at the emotional climax of the song in bar 14. Here a number of elements are employed to set the words "And shake this fragile frame"."

(Van der Watt, 390)

VARIETY

"The indications used are:"

"The dim. al niente indication is used in bars 15-7 and accompanies the words "throbbing of noontide", like the sounds of the piano, will eventually succumb to time and become nothing (niente)."

(Van der Watt, 390)

DYNAMIC ACCENTS

"There are few accentuated instances in the song. Portamento accents occur in bars 1, 2, 8 and 10 and have been discussed before. Stronger accents (>) occur in bars 10 and 14, the latter occurring with the emotional climax of the song on the word "shakes"."

(Van der Watt, 390)

"The density varies loosely between two and seven parts including both piano and voice. The thickness of the piano part is represented in the following table:"

No. of parts |

No. of bars |

Percentage |

2 parts |

1 |

6 |

4 parts |

6 |

35 |

5 parts |

9 |

53 |

6 parts |

1 |

6 |

"The two-part texture is to be found in the second half of bar 11 and the repeated D's have a thin, bell-like quality that attract attention for the start of the final, almost devastating stanza. The thickest texture occurs in bar 14 and coincides with the emotional climax of the song. The six-part piano texture is enhanced and emphasized by the arpeggio playing style in the bass part. A four- and five-part texture, a relatively thick texture, dominates (88% of the bars)."

(Van der Watt, 390-1)

"The structure of the song is represented in the following table:"

"The compositional procedure is through-composed but the structure is not absolutely clear cut. It can be shown to be binary (b. 1-10 - A and 11-17 -B) or a chain form with a recurring prelude, in a transformed state."

(Van der Watt, 391)

7. Mood and atmosphere

"The mood of the song is melancholic throughout. There is, however, a subtle development from a dejected indifference (set in G major up to bar 6), to a more embittered disillusionment (set in d minor up to bar 11) which culminates in a tragic despair and subsides into nothingness in the final bar. This modulation of the atmosphere is not simply achieved by a change of key but by a careful development of dissonance, chromaticism, accentuation and dynamic level."

(Van der Watt, 391)

General comment on style

"The vocal style is quite sympathetic to the voice and no awkward intervals occur. The harmonic language is fairly novel and more dissonant than is the norm in Finzi's writing. Structurally the song is carefully balanced with just enough internal cross reference to retain musical coherence."

(Van der Watt, 391)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is a text analysis of Thomas Hardy's poem I look into my Glass by Dr. Mark Carlisle. Dr. Carlisle extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 7th, 2010. His dissertation dated December 1991, is entitled:

Gerald Finzi: A Performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and Piano to Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page fifty-one and concludes on page fifty-eight of the dissertation.

Comments on the Poem

"The text for this song is also the final poem in Hardy's Wessex Poems, published in 1898, and like much of his writing is autobiographical in nature. Hardy wrote in his private journals, "I look in the glass. Am conscious of the humiliating sorriness of my earthly tabernacle, and of the sad fact that the best of parents could do no better for me. . . Why should a man's mind have been thrown into such close, sad, sensational, inexplicable relations with such a precarious object as his own body!" (Bailey, 111) This poem attests to the frustration of bearing the "throbbings of noontide" in the body of a man nearly sixty years old."

(Carlisle, 51-2)

"In addition to the natural frustration of physical aging, Hardy also lamented the fact that he was distressed by "hearts grown cold to me." Hardy's marriage to Emma had grown increasingly strained during the 1890's, and he began to spend less and less time with her. As a result, her resentment increased, and eventually it was clear that she had, in fact, "grown cold" to him."

(Carlisle, 52)

"These feelings found another outlet in Hardy's novel, The Well-Beloved. The character Pierston considers himself in this story: "When was it to end-this curse of his heart not aging while his frame moved naturally onward? Perhaps only with life. The person he appeared was too grievously far, chronologically, in advance of the person he felt himself to be . . . Never had he seemed so aged by a score of years as he was represented in the glass in that cold grey morning light. While his soul was what it was, why should he have been encumbered with that withering carcass, without the ability to shift it off for another . . . ?"

(Bailey, 111-2)

(Carlisle, 52)

Comments on the Music

"This piece is very short, only seventeen measures in a meter of 4/4, and is through-composed with a clear framework of two short sections. While the absence of a key signature might indicate either C major or A minor as a probable primary key, neither of these comes close to being established. In fact, key relationships are quite flexible in this song, with only the briefest of tonicizations at any given moment. Even the closing G-minor chord in measures 16-17 is not established as a legitimate 'key' with respect to the rules of functional harmony. Measures 7-12 provide the only contrast to this shifting harmonic framework when D minor is clearly but temporarily in evidence."

(Carlisle, 53)

"The song begins with a short introduction in the accompaniment using syncopated rhythms to represent the 'throbbings of noontide' that so deeply affect the poet. These syncopated rhythms return in later passages to provide a strong unifying motivical device for the song. Close intervallic relationships of seconds in the opening measure at the same time produce harmonic dissonance and tension that reflects the overall sense of frustration felt by the poet. Together, the rhythmical motive and harmonic dissonance, shown in Example 4, represent the most important distinguishing aspects of this piece."

(Carlisle, 53)

"Example 4. 'I look into my Glass,' measures 1-2." (Carlisle, 54) |

"Once the voice enters at the end of measure 2, both harmonic and rhythmical tension assume a more relaxed, conventional state, as the emphasis is now placed on the melody. This vocal melody, in terms of style, is very similar to many others composed by Finzi. It closely follows the inflection and meaning of the words, and contains a beautiful balance of conjunct and disjunct motion. Its primary difference lies in the fact that its apex occurs very early in the song, in measure 5 at the words, 'Would God it came to pass.' Finzi obviously felt that the passionate exclamation of these words was the most important dramatic moment of the poem, and supported this belief by musically providing under these words the most dramatic melodic phrasing of the song. The melody thereafter assumes a basically descending character, returning the emphasis for musical development and interest during the remainder of the song to the harmonic and rhythmical elements prominent in the opening two measures."

(Carlisle, 54)

"The second of the two short sections in this piece begins in measure 11 with a return of the syncopated 'throbbing' motive in the accompaniment. This musical sectionalization, while neither dramatic nor extensive, nevertheless corresponds well with the change of poetic thought at this moment. The poet hypothesizes in the opening lines how his life might end if his psychological condition aged in similar fashion to his physical body. However, with the words, 'But time, to make me grieve, Part steals, lets part abide," the poet adopts a more affirmable poetic stance, thus necessitating some form of corresponding musical change. The motive serves to create this change, as does a return in increased harmonic dissonance."

(Carlisle, 54-5)

"The motive is most clearly heard in measures 11-12 and 15-16, and while perhaps not as prominent as the harmonic element, is nonetheless a very important part of this section. The effect of the motive is particularly telling at the end of the song in measures 15-16, as the listener is quietly but firmly reminded of the continued beating of a youthful heart even in the later years of age."

(Carlisle, 55)

"Dissonance similar to that found at the beginning of the piece is again heard in measures 12-14, the latter being the most dissonant measure of the piece. Tension is created by intervallic relationships of a second found in these same measures, just as it was in the opening measure of the song. There is at least one such relationship in every chord in these measures, and in the most dissonant of chords, such as that which begins measure 1, there are two or even three such relationships. Although the song ends harmonically with a resolution to a simple, consonant G-minor chord in measure 16, the musical dissonance heard in the previous four measures nevertheless reflects quite well the poetic dissonance found in the relationship between the 'fragile frame at eve' and 'throbbings of noontide.'"

(Carlisle, 55-6)

"The poetry of this song reflects considerable internal resentment and animosity toward life, so performers should keep this emotional "heaviness" in mind while working within the confines of an essentially introverted musical response. Tempo in particular should be gauged to most effectively reproduce this sensation, without permitting musical stagnation to intervene. The opening tempo marking of [quarter note] = c. 50 (Adagio) is generally appropriate, but more flexibility should be allowed throughout the song than is indicated by the only two other expressive markings, poco rallentando in measure 10, and a tempo in measure 11. Measures 5-6 in particular would be better served by a slight reduction in tempo, if only to highlight the dramatic quality of the poetry at this moment. A poco rallentando should also be inserted at the end of measure 6, for this is clearly a phrasal point in the song. While tempo at the end of the song should remain relatively consistent, both performers would do well to use some slight rubato in measure 15 to underscore the great importance of the words, "throbbings of noontide.""

(Carlisle, 56)

"Dynamics follow very well the intensity of the text at any given moment and are therefore quite suitable for both performers. A dynamic level of between mezzo-forte and forte should definitely be used in measures 5-6 for dramatic purposes, but mezzo-piano or thereabouts should be used in measure 10 to end the first section in an appropriately subdued fashion. The singer may want to use a slightly higher dynamic level than piano for purely practical reasons at the end of the song; it is relatively low in the range of the male high voice, and would probably make the final words inaudible in all but the smallest of recital halls. However, he should also keep in mind that there must be a noticeable decrescendo from the middle of measure 14 to the end of measure 15, without any loss of communicative energy, for the ending to be truly effective. Therefore, if a slightly higher dynamic level is used by the singer at this point, the level used in measure 14 should be gauged accordingly." (Carlisle, 57)

"There is little in this piece that should cause any serious technical difficulties for a tenor, although one with a very light voice might find some difficulty handling the demands of the lower tessitura at the end of the song. The highest note in the range is g¹, sung only briefly in measure 5, and the tessitura is the lowest of any song in this set. By far the most serious demands on the performer of this song are interpretive; an artistic rendering of the text requires that the performer be able to empathize with those who suffer the emotional effects of advancing age combined with decreasing physical facility. While this concept can no doubt be "interpreted" to some extent by even the most youthful performers, it seems appropriate to suggest that this piece is not well-suited for very young singers. It is not a difficult piece to "sing," but an insightful and rewarding performance really requires the interpretive skills found in singers at the graduate level and beyond." (Carlisle, 57-8)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of I look into my glass by Leslie Alan Denning. Dr. Denning extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated May 1995, is entitled:

A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page eighty and concludes on page eighty-two of the dissertation.

"The final exultation of 'The Market Girl' is quickly forgotten in the bitter mood of the following song, 'I Look Into My Glass,' written in 1937. Hardy's poem of the same name was published in 1898 as the last of the fifty-two verses in Wessex Poems. The efforts of poet and composer combine to create a masterpiece in miniature within the song's seventeen measures. Finzi paints the text with an intense stroke reminiscent of Hugo Wolf as he depicts the throbbing passion within an old body as well as the conflict between emotional desire and physical age."

(Denning, 80-1)

"Finzi's approach is both sparse and direct. The prelude to the vocal entrance shows no clear basis of tonality, being full of confusing dissonances. The voice line again mimics speech but here is filled with emotion. The accompaniment is simple with obvious use of dissonance, bearing the influence of more progressive harmony present in his later songs (musical Example 22)."

(Denning, 81)

"Example 22: I Look Into My Glass, Measures 4-5." (Denning, 81) |

"Finzi's conversational voice line appears unforced, natural as he clenches Hardy's biting words which seem familiar but not expected in poetry. Again Finzi has used altered meters to assist with text setting (musical Example 23)."

(Denning, 81)

"Example 23: I Look Into My Glass, Measures 9-11." (Denning, 81) |

"Note that in measure eleven the period of waiting is punctuated by the apparent tolling of a bell marking the passing of time. The last verse grows harmonically intense harmonically with Finzi's use of seventh chords which eventually fade, leaving only the G-major [minor] triad. This song is most effective with so much to say in so little time; the equivalent to a grand operatic scena. This is what makes art-song a special form and certainly 'I Look Into My Glass' commands the respect of both performer and audience."

(Denning, 82)