To Lizbie Browne

Poet: Thomas Hardy

Date of poem: undated

Publication date: 1901

Publisher:

Collection: Poems of the Past and the Present

History of Poem:

Poem

To Lizbie Browne |

||

|---|---|---|

I |

||

| 1 | Dear Lizbie Browne, | |

| 2 | Where are you now? | |

| 3 | In sun, in rain? - | |

| 4 | Or is your brow | |

| 5 | Past joy, past pain, | |

| 6 | Dear Lizbie Browne? | |

II |

||

| 7 | Sweet Lizbie Browne, | |

| 8 | How you could smile, | |

| 9 | How you could sing? - | |

| 10 | How archly wile | |

| 11 | In glance-giving, | |

| 12 | Sweet Lizbie Browne! | |

III |

||

| 13 | And, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 14 | Who else had hair | |

| 15 | Bay-red as yours, | |

| 16 | Or flesh so fair | |

| 17 | Bred out of doors, | |

| 18 | Sweet Lizbie Browne? | |

IV |

||

| 19 | When, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 20 | You had just begun | |

| 21 | To be endeared | |

| 22 | By stealth to one, | |

| 23 | You disappeared | |

| 24 | My Lizbie Browne! | |

V |

||

| 25 | Ay, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 26 | So swift your life, | |

| 27 | And mine so slow, | |

| 28 | You were a wife | |

| 29 | Ere I could show | |

| 30 | Love, Lizbie Browne. | |

VI |

||

| 31 | Still, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 32 | You won, they said, | |

| 33 | The best of men | |

| 34 | When you were wed. . . . | |

| 35 | Where went you then, | |

| 36 | O Lizbie Browne? | |

VII |

||

| 37 | Dear Lizbie Browne, | |

| 38 | I should have thought, | |

| 39 | 'Girls ripen fast,' | |

| 40 | And coaxed and caught | |

| 41 | You ere you passed, | |

| 42 | Dear Lizbie Browne! | |

VIII |

||

| 43 | But, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 44 | I let you slip; | |

| 45 | Shaped not a sign; | |

| 46 | touched never your lip | |

| 47 | With lip of mine, | |

| 48 | Lost Lizbie Browne! | |

IX |

||

| 49 | So, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 50 | When on a day | |

| 51 | Men speak of me | |

| 52 | As not, you'll say, | |

| 53 | 'And who was he?' - | |

| 54 | Yes, Lizbie Browne! | |

(Hardy, 131-2) |

||

Content/Meaning of the Poem:

Speaker:

Setting:

Purpose:

Idea or theme:

Style:

Form:

Synthesis:

Published comments about the poem:

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Musical Analysis

Composition date:

Publication date:

Publisher: Boosey & Hawkes - Distributed by Hal Leonard Corporation

Tonality:

Transposition:

Duration:

Meter:

Tempo:

Form:

Rhythm:

Melody:

Texture:

Vocal Range:

Tessitura:

Dynamic Range:

Accompaniment:

Published comments about the music:

Pedagogical Considerations for Voice Students and Instructors:

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

| Pitch Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pitch | stanza 1 |

stanza 2 |

stanza 3 |

stanza 4 |

total | |

highest |

A |

|||||

G |

||||||

F |

||||||

E |

||||||

D |

||||||

middle C |

||||||

B |

||||||

A |

||||||

G |

||||||

F |

||||||

lowest |

E |

|||||

| Rhythm Duration Analysis of Vocal Line | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stanza 1 | stanza 2 | stanza 3 | stanza 4 | total | |

16th note |

|||||

8th note |

|||||

dotted 8th |

|||||

quarter note |

|||||

dotted quarter |

|||||

triplet |

|||||

half note |

|||||

dotted half |

|||||

stanza total |

|||||

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Audio Recordings

Over Hill and Valley: Songs of Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

The British Music Collection: Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

Song Recital |

|

|

|

Songs: Brahms - Faure - Finzi - Schubert |

|

|

|

The Songs of Gerald Finzi to Words by Thomas Hardy

|

|

|

|

A Treasury of English Song |

|

|

|

Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

The English Song Series - 15 |

|

|

|

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

The following is an analysis of To Lizbie Brown by Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt. Dr. Van der Watt extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on October 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated November 1996, is entitled:

The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt comes from Volume II and begins on page 216 and concludes on page 227. To view the methodology used within Dr. Van der Watt's dissertation please refer to: Methodology - Van der Watt.

1. Poet

Specific background concerning poem:

"To Lizbie Brown" comes from Hardy's second volume of poems, Poems of the Past and the Present (1901), and is undated. Of the volume Seymour-Smith says:

In Poems of the Past and the Present, he (Hardy) probably comes nearest to how he really felt (Seymour-Smith, 635)

It contains the famous War Poems, Poems of Pilgrimage, Miscellaneous Poems (the section from which To Lizbie Brown, God-Forgotten and In Tenebris come), and Imitations and Retrospect (which contains I have Lived with Shades and To the Unknown God).

Of the poem To Lizbie Brown, Hardy in the hand of his first wife Emma, writes in the 1928 biography:

There was another young girl, a gamekeeper's pretty daughter, who won Hardy's boyish admiration because of her beautiful bay-red hair. But she despised him, as being two or three years her junior, and married early. He celebrated her later on as "Lizbie Brown". (Florence Hardy,33)

2. Poem

To Lizbie Brown |

||

|---|---|---|

I |

||

| 1 | Dear Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 2 | Where are you now? | b |

| 3 | In sun, in rain? - | c |

| 4 | Or is your brow | b |

| 5 | Past joy, past pain, | c |

| 6 | Dear Lizbie Brown? | a |

II |

||

| 7 | Sweet Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 8 | How you could smile, | d |

| 9 | How you could sing? - | e |

| 10 | How archly wile | d |

| 11 | In glance-giving, | e |

| 12 | Sweet Lizbie Brown! | a |

III |

||

| 13 | And, Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 14 | Who else had hair | f |

| 15 | Bay-red as yours, | g |

| 16 | Or flesh so fair | f |

| 17 | Bred out of doors, | g |

| 18 | Sweet Lizbie Brown? | a |

IV |

||

| 19 | When, Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 20 | You had just begun | h |

| 21 | To be endeared | i |

| 22 | By stealth to one, | h |

| 23 | You disappeared | i |

| 24 | My Lizbie Brown! | a |

V |

||

| 25 | Ay, Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 26 | So swift your life, | j |

| 27 | And mine so slow, | k |

| 28 | You were a wife | j |

| 29 | Ere I could show | k |

| 30 | Love, Lizbie Brown | a |

VI |

||

| 31 | Still, Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 32 | You won, they said, | l |

| 33 | The best of men | m |

| 34 | When you were wed. . . . | l |

| 35 | Where went you then, | m |

| 36 | O Lizbie Brown? | a |

VII |

||

| 37 | Dear Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 38 | I should have thought, | n |

| 39 | 'Girls ripen fast,' | o |

| 40 | And coaxed and caught | n |

| 41 | You ere you passed, | o |

| 42 | Dear Lizbie Brown! | a |

VIII |

||

| 43 | But, Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 44 | I let you slip; | p |

| 45 | Shaped not a sign; | q |

| 46 | touched never your lip | p |

| 47 | With lip of mine, | q |

| 48 | Lost Lizbie Brown! | a |

IX |

||

| 49 | So, Lizbie Brown, | a |

| 50 | When on a day | r |

| 51 | Men speak of me | s |

| 52 | As not, you'll say, | r |

| 53 | 'And who was he?' - | s |

| 54 | Yes, Lizbie Brown! | a |

(Hardy, 131-2) |

||

The persona (possibly the poet) addresses a lost beloved from his youth. He recalls her qualities ("smile, hair, singing" and complexion), relates, honestly, the story of how he loved her from afar but was unable to act swiftly enough to gain her love. He expresses regret for his slowness without scorning or begrudging her probable happiness. The poem has a rueful twist in the final stanza where the poet surmises that when he himself is dead and men speak of him, Lizbie Brown will not so much as know his name, most probably because he had hardly made himself known to her. The tone of the poem is at one and the same time pensive, honest, introspective, regretful, generous (in praise), unblaming and realistically wistful.

The poem is an ode mixed with qualities of a dramatic love-lyric. It is intensely personal, private and self-revealing of a mind not shirking painful investigation of private loss.

The poem consists of nine sestets with a varied rounded rhyme scheme: abcbca adcdca etc. The meter consist mainly of iambic dimeters (l. 2-5 of most stanzas) while the outer lines of each stanza, containing the name, can either be seen to open with a spondaic or dactylic foot.

The poem details the former, a one-sided love affair of a man no longer young who is regretting the missed opportunities of his youth. The mood is musing and retrospective. The short lines (two feet each) create the effect of a dramatic narrative while the eighteen repetitions of the girl's name emphasize not only emphasize the extent of her existence in the persona's imagination but also the relentless recurrence of this specific image. The first three stanzas concentrate exclusively on reconstructing the image of the young girl then the personal refers to his own secret love and inability, for whatever reason, to act on it. He then comments on her apparent happiness and his regrettable loss and finally implies that she hardly knows of his existence.

Setting

1. Timbre

VOICE TYPE/RANGE

The song is for baritone and the specific range is a perfect eleventh above the second B flat below middle C. This voice type is particularly suitable for the poem's circumstances and meaning.

The piano accompaniment ranges from a single occurrence of F (b. 29) above middle C to the G a fourth and two octaves below middle C, restricting the range to just less than two octaves. This deliberate restraint is in sensitive keeping with the non-extremist character of the poem: there is no excess of event or emotion, "Things are what they are, and will be brought to their destined issue" (Seymour-Smith, 78). Similarly, the piano accompaniment in the range and register, harmonic language, dynamic application follows this line of thought: no excess.

The middle to low register of the piano is employed to ensure the warmth in the sonority necessary for the gentle meditative undertone in the text. (There are nine bars, 14% of the total in which the right hand is notated in the bass clef). There are no indications of pedal use while pedalling would certainly be necessary in the largely chordal accompaniment. Care will have to be taken with certain chords which are very low and could easily sound murky if the pedal is used carelessly (b. 17-18, 20, 36-37).

There is substantial amount of staccato indications in the prelude (b. 1-6) and postlude (b. 63-66) and four other isolated occurrences (b. 41, 42, 56, 57) which reinforces the detachment of the lover from the beloved and helps to set the scene for the isolation of the persona. There are many portamento accents (b. 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 15, 24-27, 46, 49, 52, 57, 60, 62, 63, 65) all of which have the same purpose namely gently to accentuate a melodic moment. Only one stronger accent (>) occurs in bar 30 to emphasize the modified imitation of a preceding melodic line with the text, "My Lizbie Brown". This single placement of an accent reveals something of the composer's interpretation of the text: the emphasis on the fact, introduced as an afterthought, that the girl could have been his ("My Lizbie").

The song has a quiet, meditative atmosphere carefully balanced between retrospective regret and resigned acceptance of reality. There is little trace of sadness or despair but a pensive longing and a sense of being haunted by his own failure to declare his love.

2. Duration

METRE

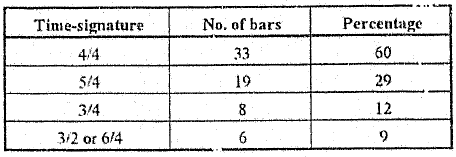

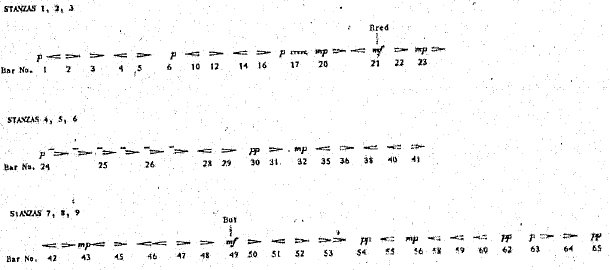

The prominence of iambic dimeters has resulted in 60% use of common time. The composer does not commit himself to a time-signature in an attempt to achieve a suppleness of metre. Speech rhythm and metre are followed closely with the result that the musical metre changes often, too often to put in tabular form. The summary is as follows:

The reasons for these changes, apart from the general one stated above, are:

- to prolong notes before the start of a new stanza (b. 5, 17, 23, 36, 42, 48, 55, 63),

- to allow a solo vocal instance (b. 6, 9, 10, 15, 37, 39, 43, 56, 62),

- to emphasize certain words, placing them on the strong beat (b. 9, 11, 12, 17, 20, 23, 35, 37, 38, 40, 50, 59, 61)

The most prominent metre is prevalent in the prelude (b. 1-6), postlude (b. 63-66) and for ten bars from bar 23-32. The stability of metre here coincides with the persona's reference to his own secret love, of that at least, he was sure, hence the surer metric flow.

Rhythmic motifs

A single rhythmic motif and its subtle variations dominates in the song. Motif 1, consisting of a crotchet two quavers an an minim (the Lizbie Brown motif) occurs 16 times in the voice and 32 times in the piano part (a total of 48 or in 73% of the bars). The variations are numerous; the initial crotchet is replaced by a minim, crotchet rest quaver, two quavers or a dotted crotchet and quaver while the final minim is shortened and lengthened randomly. No other motif establishes itself strongly enough to be considered.

Rhythmic activity vs. Rhythmic stagnation

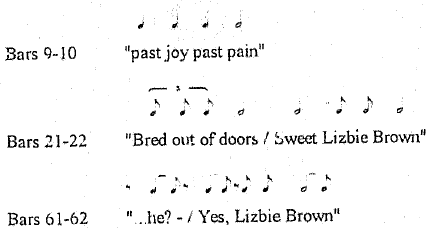

As far as rhythmic activity is concerned, there is an ebb and flow. The rests in the piano part (listed before) are used firstly to isolate important vocal moments, but also to complement the very short lines of the text and the way natural thought occurs: in short bursts. There are, furthermore, a number of text-related rhythmic stagnations. In each case these occur for the sake of emphasis and considering the meaning as if in slow-motion:

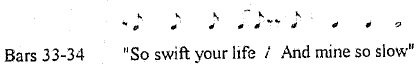

Finally, the rhythmic flow is carefully and aptly controlled and contrasted in the lines:

Rhythmically perceptive, erroneous and interesting settings

A number of words and phrases have been set with careful perceptiveness:

The final stanza (l. 49-54) has been set most successfully. The punctuation of the text is followed meticulously: every comma is furnished with and appropriate rest. The effect is dramatic and haunting.

Lengthening of voiced consonants

Every word in the text containing an N, M, or L (except "Brown" in bar 24) has been prolonged by the rhythmic value of a dotted crotchet or longer. The word "Brown" occurs 18 times and only once is not prolonged. (Other words are, "now, rain, pain, smile, wile, one, life, slow, love, won, men, sigh, mine, lip, mine, me".)

The tempo indication is Tempo commodo ![]() There is a further footnote which concerns the execution of the tempo and metre in performance and at the same time provides a valuable insight into Finzi's awareness of the limitations of notation as well as the importance of the participatory role of the performer (both singer and pianist) in the re-creation of a song during performance viz:

There is a further footnote which concerns the execution of the tempo and metre in performance and at the same time provides a valuable insight into Finzi's awareness of the limitations of notation as well as the importance of the participatory role of the performer (both singer and pianist) in the re-creation of a song during performance viz:

The beat should be flexible and wayward, with

as no more than a touch-stone. Such suppleness cannot, of course, be determined by directions on paper, and the modifications of speed which are been given should only be considered as an outline.

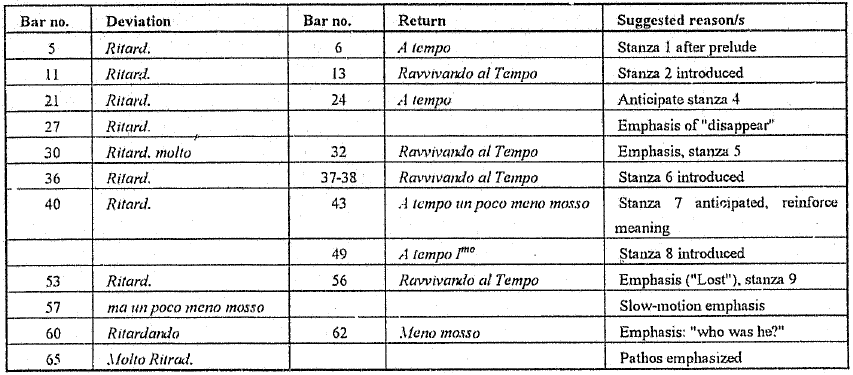

Tempo variation

Numerous variations in tempo occur. This flexible tempo is in keeping with meditative character of the song.

3. Pitch

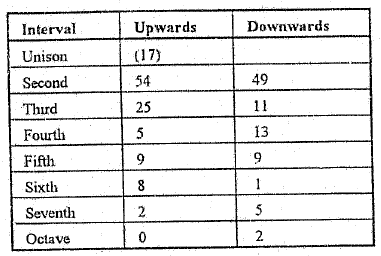

An intervals analysis of the vocal line is represented in the following table:

There are 103 rising intervals (49%), 90 falling intervals (43%) and 17 stationary intervals (8%). The smaller intervals (unisons, seconds and thirds) account for 156 (or 74%) of the total number, the larger intervals (fourths and larger) for 54 (or 26%) and repeated intervals for 17 (or 8%). The high incidence of smaller intervals indicates the composer's sympathetic consideration of the voice. Specific settings, associated with larger intervals are tabled below. The 18 settings of the name "Lizbie Brown" will be discussed separately:

The long list of specifically set words in an overwhelmingly conjunct context, is indicative of the care taken to marry textual and musical meaning. The similar setting of the juxtaposed concepts "past joy, past pain" is noteworthy: though "joy" is set a third higher than "pain", both are set with a downward fourth. The composer here enhances the underlying meaning of the poet that these two extremes are really two sides of the same coin.

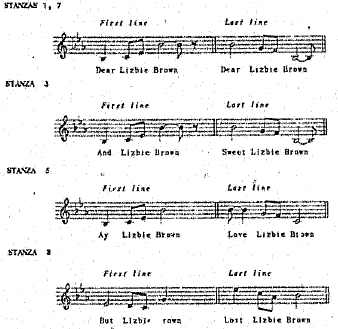

The 18 settings of the name "Lizbie Brown" and its variety of preceding words, are so revealing and interesting that they demand a careful analysis:

Melodic curve

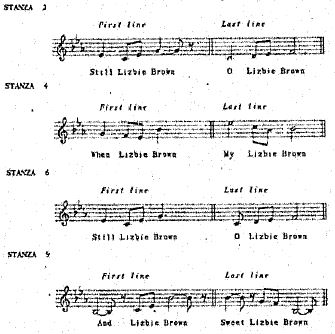

A melodic curve of the vocal line is represented below. Note the similarity between odd numbered stanzas, the similarity between stanzas 2 and 6 and between stanzas 4 and 8:

The similarity in the odd-numbered stanzas is confined to the pitch arrangement except for the final note of stanza 5 (b. 36) while the rhythmic, harmonic, and dynamic material differs subtly. The melodic material of the opening stanza becomes a musical refrain with varying texts, akin to an ancient ballad. Stanzas 2 and 6 varying considerably in melodic detail from stanza 1, though alike in spirit, have the same relation to one another. And such is the case with stanzas 4 and 8 though the link is not as close. Stanza 8 starts a third lower, a suitable change in relation tot he meaning of the text in which the persona states that he lost the girl.

Climaxes

Vocal climaxes are given below:

There is no single vocal climax but all the E flats occur on important words, even the "And" which is the start of the girl's final question. The real climax of the song occurs just prior to the line "My Lizbie Brown" (l. 24, stanza 4) in the piano anticipating it while at the same time there is a subtle directional inversion of the final interval of the motif that accompanies the word, "disappeared". This musical reference to the girl's disappearance is also the birth of the climactic sigh: "My Lizbie Brown". A comparison with the parallel moment (l. 48, stanza 8), "Lost Lizbie Brown" clarifies the importance of bars 29-30. In bar 53 the build up to "lost" is gradual and gentle, it does not reach the F and the harmony is now ii7 where it had been V6 before. It is at this point that the persona's acceptance of his fate is sensitively captured by Finzi's setting.

Phrase lengths

Phrase lengths for vocal purposes are of varied duration: stanzas 1, 2, 5, and 9 contain shorter phrases and sub-phrases where breathing is comfortable. Stanzas 7 and 8 have a mixture of lengths while phrases in stanzas 3, 4 and 6 will need slight rhythmic modification to accommodate breathing.

The basic key is an unambiguous E flat major with but one short modulation in bar 48 to c minor. The progression from 482 - 491 is, c: iv42 (G - appoggiatura) - V64 - i. The cadential moment is a Phrygian cadence and the dramatic effect in an otherwise tonal context, points forward to the imminent reference to the loss, "I let you slip".

Chromaticism

The lack of any kind of chromaticism, bar the single occurrence of a B natural which is not chromatic in the key of c harmonic minor, is not an accident. This almost pan-diatonic approach on E flat has a numbing, trapped effect. It is as if the composer tries to isolate the persona and his feelings through the use of a single tonal focus.

HARMONY AND COUNTERPOINT

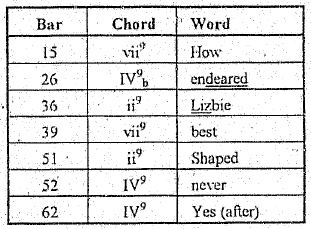

In a largely tonal context the occurrence of dissonance is of importance. There is, furthermore, an absence of strong dynamic accents (an aspect that will be discussed later) and therefore harmonic accents (dissonance or interesting constructions) fulfil this role of emphasis:

Other harmonic features which establish themselves are strings of first inversion and second inversion chords. These have a musically unifying effect and they help to keep the atmosphere consistent but do not directly reinforce the textual meaning:

First inversion: b. 21-3, 7, 162-5, 332-341, 402-412, 455-462, 464-473, 575-591

Second inversion: b. 355-352, 565-574

The final B flat of the song in bar 66 leaves the song harmonically open-ended. It is as if the song disintegrates into nothing. The implication is that it could be taken as either a perfect or an imperfect ending, a choice the composer leaves to the listener. If a perfect cadence is imagined, the interpretation follows, ironically, that all is lost. If, however, an imperfect ending is imagined, it might be interpreted as though the persona is given hope by the composer that the same fate that sealed his lot, may smile on him gently in another set of circumstances.

Non-harmonic tones

There are two important non-harmonic tones, firstly the appoggiatura. This note occurs in the descending version of the "Lizbie Brown" motif (b. 22 treble - G) and occurs quite frequently as a consequence. Appoggiaturas, traditionally, have a strong emotional effect and when they are accented the effect is even stronger. In this song they are little needle pricks of pathos and they are present throughout (b. 2(twice), 4, 5, 11, 12(twice), 14, 22, 23, 36, 38, 47, 48, 52, (not in 54 and 55, due to the harmonic variation), 63(twice)). Secondly, the escape tone is used extensively. The instance where it is most applicable is with the word, "disappeared" (b. 281 - C), where the melodic feature reincarnates the meaning of the text by disappearing or escaping itself. This same emotional content is present in scores of other places (b. 10 voice, 16 voice, 174 piano, 20 voice, 28 voice, 34 voice, 39 voice, 40 voice, 413 piano, 423 piano, 45 voice, 454 piano, 50 voice, 58 voice).

Harmonic devices

There are a few short inverted pedal notes in the song (b. 27-28, 36-37, 62, 65-66) which all have the same effect, namely to slow down the harmonic activity to bring the phase to a natural close. The function is therefore structural rather than semantic.

Counterpoint

Short imitations or echoes of vocal material in the piano part are frequently used in the song. These strengthen the retrospective mood of the song since the piano often looks back at what the voice has said. It also allows the listener to repeat the conceptual meaning in his mind along with the pianistic repetition (b. 11-12 voice - 12 piano, 16-17 voice - 17-18 piano, 22-23 voice - 23 piano, 34-35 voice - 35 piano, 47 voice - 47-48 piano). There are also a number of modified imitations during which the effect mentioned before is still present but more subtly so (b. 27-28 voice - 28-29 piano, 30 voice - 30 piano, 35-36 voice - 36-37 piano, 40-41 voice - 41-42 piano, 44-45 voice - 45 piano, 54 voice - 54-55 piano).

Loudness variation is given in the following summary:

There are also a number of specific indications for the voice, which are listed below:

- Bar 15 "How you could sing?"

- Bar 30 "My Lizbie Brown"

- Bar 32 "Ay Lizbie Brown"

- Bar 38-39 "You won the best of men"

- Bar 54 "Lost Lizbie Brown"

- Bar 55 "So Lizbie Brown"

- Bar 60 "And who was he?"

These largely coincide with the indication in the piano which leads one to believe that the voice should follow the piano dynamics where not stated otherwise.

FREQUENCY

There are 60 dynamic indications in the 66 bars (91%). This high incidence is attributed to the composer's meticulousness in the specific song as a result of its sensitive character.

RANGE

The range is quite narrow from pp - mf and the only two mf indications (b. 21 "Bred" and 49 "But). The quietness ensured by these indications are in keeping with the introspective and meditative atmosphere of the song. There is no sudden change of level and this supports the persona's gradual acceptance of the reality of his loss. The pp is also only used twice (b. 30 "My" and 62 "Yes") both of which accompany pivotal recognition on the part of the persona: by understating the level the composer both emphasizes and softens the blow of this recognition.

VARIETY

The indications used are:

DYNAMIC ACCENTS

The portamento accents are numerous and were listed under references to articulation earlier. They all fulfil the purpose of mild accentuation and are used aptly in this song's specifically created context. Just following the pianistic climax (b. 29), a single stronger accent is used in bar 303 which coincides with a modified imitation of the motif used with the text, "My Lizbie Brown". This accent highlights the 'afterthought' character of all these imitations discussed earlier.

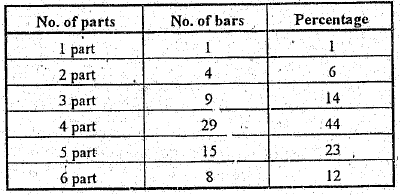

The density varies loosely between one and seven parts including both piano and voice. The thickness of the piano part is represented in the following table:

The single pitch B flat in the final bar refers back to the octave B flat of the very first bar. Its possible harmonic interpretations have been discussed before and the textural considerations support the idea of a fizzling out into virtual nothingness. The most prominent textural use is that of a four- or five-part chordal accompaniment. These two textures roughly take care of 67% of the bars. Bars 24-27 have a conspicuous six-part texture. This texture coincides with the more stable common-time metric flow and therefore enhances the confidence the personal feels in expressing the one thing that he is sure of: his undeclared love for Lizbie Brown.

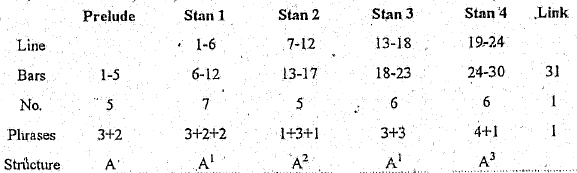

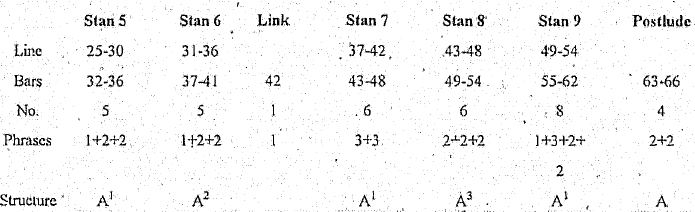

The structure of the song is represented in the following table:

The odd-numbered stanzas take on refrain-like qualities while stanzas 2 and 6, and 4 and 8 are variations on one another respectively. The song is thus varied strophic and really in unitary form due to the tonal and material uniformity fraught with subtle and continuous variation.

7. Mood and atmosphere

The poem suggests an older man in pensive, regretful mood musing about a love lost through his own lack of action and slowness in awakening and expression. There is a certain sense of preoccupation with the qualities of the idealized beloved. This is also an honest review, typically Hardian, of his own inability to act on his feelings. This sensitive mixture between regret, longing, elation at the pleasant memory and shrinking from the pain yet facing it, is carefully set by the composer with intertwined, subtly varying musical motifs, a deliberately isolated tonality (with a single modulation at the realization of loss) and gentle dynamic use.

General comment on style

The voice has been treated with sympathy while many larger intervals occur (nine 6th intervals, seven 7th intervals and 2 octave leaps). The escape tone and appoggiatura feature prominently and are throughout directly related to the meaning of the song. The composer's mastery at the technique of subtle variation is exhibited here with the command of melodic and rhythmic material resulting in a tightly controlled formal structure. The dichotomy of emotions: Regret and acceptance, longing and elation is carefully captured.

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of To Lizbie Brown by Curtis Alan Scheib. Dr. Scheib extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on February 17th, 2012. His dissertation dated 1999, is entitled:

Gerald Finzi's Songs For Baritone On Texts By Thomas Hardy: An Historical And Literary Analysis And Its Effect On Their Interpretation

This excerpt begins on page forty-five and concludes on page forty-six.

To Lizbie Browne |

||

|---|---|---|

I |

||

| 1 | Dear Lizbie Browne, | |

| 2 | Where are you now? | |

| 3 | In sun, in rain? - | |

| 4 | Or is your brow | |

| 5 | Past joy, past pain, | |

| 6 | Dear Lizbie Browne? | |

II |

||

| 7 | Sweet Lizbie Browne, | |

| 8 | How you could smile, | |

| 9 | How you could sing? - | |

| 10 | How archly wile | |

| 11 | In glance-giving, | |

| 12 | Sweet Lizbie Browne! | |

III |

||

| 13 | And, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 14 | Who else had hair | |

| 15 | Bay-red as yours, | |

| 16 | Or flesh so fair | |

| 17 | Bred out of doors, | |

| 18 | Sweet Lizbie Browne? | |

IV |

||

| 19 | When, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 20 | You had just begun | |

| 21 | To be endeared | |

| 22 | By stealth to one, | |

| 23 | You disappeared | |

| 24 | My Lizbie Browne! | |

V |

||

| 25 | Ay, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 26 | So swift your life, | |

| 27 | And mine so slow, | |

| 28 | You were a wife | |

| 29 | Ere I could show | |

| 30 | Love, Lizbie Browne. | |

VI |

||

| 31 | Still, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 32 | You won, they said, | |

| 33 | The best of men | |

| 34 | When you were wed. . . . | |

| 35 | Where went you then, | |

| 36 | O Lizbie Browne? | |

VII |

||

| 37 | Dear Lizbie Browne, | |

| 38 | I should have thought, | |

| 39 | 'Girls ripen fast,' | |

| 40 | And coaxed and caught | |

| 41 | You ere you passed, | |

| 42 | Dear Lizbie Browne! | |

VIII |

||

| 43 | But, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 44 | I let you slip; | |

| 45 | Shaped not a sign; | |

| 46 | touched never your lip | |

| 47 | With lip of mine, | |

| 48 | Lost Lizbie Browne! | |

IX |

||

| 49 | So, Lizbie Browne, | |

| 50 | When on a day | |

| 51 | Men speak of me | |

| 52 | As not, you'll say, | |

| 53 | 'And who was he?' - | |

| 54 | Yes, Lizbie Browne! | |

(Hardy, 131-2) |

||

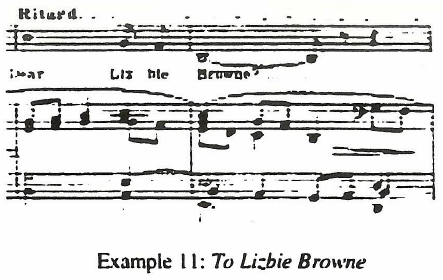

the nine verses of Hardy's poem relate the bittersweet tale of a missed opportunity. The love is fondly remembered but time seems to have only sharpened the sense of loss. The four syllable refrains at the end of each stanza (example 11), musical in and of themselves, seem to respond easily to Finzi's lyric treatment.

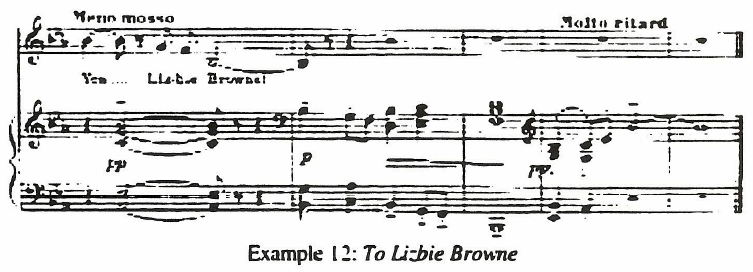

There is an intimacy and directness in his setting as well as great suppleness. Finzi cautions in a footnote at the beginning of the song that the beat should be flexible and wayward, and encourages the singer to look past the notes for a natural expression. Present also is the first appearance of the marking, Ravvivando al Tempo, which Finzi used here and in later works to indicate the fluidness of movement he desired. The harmonic language is Finzi at his most conservative and most English, almost purely diatonic in the tradition of Elgar and Parry. (Banfield, 209) It serves the text well however, carrying the bittersweet nostalgia of the ballad. Also at work here is Finzi's technique of repeating motives in the piano that have previously been married to text or images. This technique, a sort of trope, becomes increasingly present in his style. Here it is most consistently present in the four-note figure given to "Dear Lizbie Browne" at the beginning. The four-note figure reappears in various shapes and places, making a final appearance in the piano alone, the final note left to hang in the air with the poet's remorse (example 12).

The preceding was an analysis of To Lizbie Browne by Curtis Alan Scheib. Dr. Scheib extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on February 17th, 2012. His dissertation dated 1999, is entitled:

Gerald Finzi's Songs For Baritone On Texts By Thomas Hardy: An Historical And Literary Analysis And Its Effect On Their Interpretation

The excerpt began on page forty-five and concluded on page forty-six.