Ditty

- Musical Analysis Section

- Audio Recordings Section

- Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

- Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

- Carlisle - Gerald Finzi: A performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and

- Denning - A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

- Rogers - A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas Hardy

- Bray - An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

- John Keston - Two Gentlemen from Wessex, The Relationship of Thomas Hardy's Poetry to Gerald Finzi's Music

Poet: Thomas Hardy

Date of poem: 1870 (Purdy, 98)

Publication date: December 11, 1898 with Wessex Poems.

Publisher: Macmillan Publishing Company

Collection: Wessex Poems - Published December 11, 1898.

(Bailey, 17)

History of Poem: Richard Little Purdy records 1870 for the date as to when Hardy wrote the poem. Purdy also points out the initials ELG on the poem refer to Hardy's first wife Emma Lavinia Gifford. The poem was to have been written after Hardy's visit to St. Juliot Rectory in Cornwall in March of 1870. Purdy offers evidence to this time-line by referring to the Hardy biography, The Early Life of Thomas Hardy, written by Hardy's second wife, Florence Hardy. Purdy also mentions in his comments about the poem that the text was altered from: "Some loves die" to "Some forget." (Purdy, 98-9) It would be interesting to learn as to when this alteration occurred, if it was around the time when the poem was written or years later when the relationship between Thomas and Emma was growing apart.

Hardy was beginning his career as an architect when he wrote the poem and was living in a not so pleasant part of London. His physical and mental health were in decline possibly because of his accommodations as well as being homesick for the countryside. James Osler Bailey records in his comments about the poem that Hardy "seems to have passed the days in Town desultorily and dreamily—mostly visiting museums and picture-galleries, and it is not clear what he was waiting for there. In his leisure he seems to have written the ‘Ditty’ in Wessex Poems.”

(Bailey, 59-60)

Kenneth Marsden comments that Ditty is the only poem Hardy dedicated directly to his first wife Emma. He also believes the poem is unusual for Hardy in that it was "not a product of the typical lying-fallow period." (Marsden, 54)

For additional commentary as to the history of the poem please refer to: Background and History.

Poem

Ditty

|

||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | BENEATH a knap where flown | a |

| 2 | Nestlings play, | b |

| 3 | Within walls of weathered stone, | a |

| 4 | Far away | b |

| 5 | From the files of formal houses, | c |

| 6 | By the bough the firstling browses, | c |

| 7 | Lives a Sweet: no merchants meet, | d |

| 8 | No man barters, no man sells | e |

| 9 | Where she dwells. | e |

| 10 | Upon that fabric fair | f |

| 11 | ‘Here is she!’ | g |

| 12 | Seems written everywhere | f |

| 13 | Unto me. | g |

| 14 | But to friends and nodding neighbours, | h |

| 15 | Fellow-wights in lot and labours, | h |

| 16 | Who descry the times as I, | i |

| 17 | No such lucid legend tells | e |

| 18 | Where she dwells. | e |

| 19 | Should I lapse to what I was | j |

| 20 | Ere we met; | k |

| 21 | (Such will not be, but because | j |

| 22 | Some forget | k |

| 23 | Let me feign it) – none would notice | l |

| 24 | That where she I know by rote is | l |

| 25 | Spread a strange and withering change, | m |

| 26 | Like a drying of the wells | e |

| 27 | Where she dwells. | e |

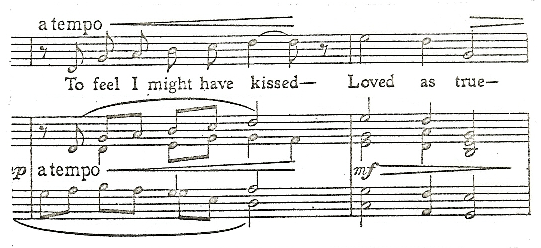

| 28 | To feel I might have kissed – | n |

| 29 | Loved as true – | o |

| 30 | Otherwhere, nor Mine have missed | n |

| 31 | My life through, | o |

| 32 | Had I never wandered near her, | p |

| 33 | Is a smart severe – severer | p |

| 34 | In the thought that she is nought | q |

| 35 | Even as I, beyond the dells | e |

| 36 | Where she dwells. | e |

| 37 | And Devotion droops her glance | r |

| 38 | To recall | s |

| 39 | What bond-servants of Chance | r |

| 40 | We are all. | s |

| 41 | I but found her in that going | t |

| 42 | On my errant path unknowing, | t |

| 43 | I did not out-skirt the spot | u |

| 44 | That no spot on earth excels, | e |

| 45 | - Where she dwells! |

e |

(Hardy, 17-8) |

||

Content/Meaning of the Poem:

Mark Carlisle makes the following comments in his dissertation about the meaning of the poem as well as some definitions for some of the text: "this poem, like "A Young Man's Exhortation," is also somewhat difficult for those unfamiliar with Romantic English poetry. While the sentiment expressed in these verses is a common one, the language used is somewhat archaic and esoteric in comparison to that used today. While a full translation of the whole poem is not in this case necessary, several terms still need definition: "knap" - the crest of a hill; "flown Nestlings" - birds that have just left the nest; "firstling" - first-born; "fellow-wights" - fellow human beings; "descry" - discern, discover; "feign" - to give a false appearance; "a smart severe" - a painful emotional cut; "nought" - nothing; "out-skirt" - go around."

(Carlisle, 98-9)

Dr. Carlisle also points out in his description of the poem that the fourth stanza is "particularly difficult to understand" therefore he composed "a modern, paraphrased version."

(Carlisle, 99)

"To realize that I might have kissed and loved |

Gerhardus Van der Watt, who has written a tremendously valuable dissertation on all of Finzi's songs that utilize Thomas Hardy texts has also made some comments as to possible interpretations of this poem. To view these comments please refer to: Content - Van der Watt.

Speaker: Thomas Hardy is the most likely candidate for the speaker of the poem.

Setting: Sarah Bird Wright the author of Thomas Hardy A to Z records that the setting for the poem is St. Juliot Church. She bases this opinion on Hardy's descriptive text in the poem and more specifically "walls of weathered stone." (Wright, 59)

Purpose: The purpose of the poem is to reference that things in life happen so often by chance.

Idea or theme: The theme, much like the purpose, seems to point towards "chance" as the idea that binds the poem together but also one must not lose sight of the fact that Hardy is deeply in love with the subject of the poem. Love, therefore must be considered the secondary theme. Hardy must have been perplexed by the things in his life that seemed to have come by chance according to Sarah Bird Wright. She goes on to say: "the poem proposes that all people are "bond-servants of Chance" and that Hardy finds it painful to think he might never have met his wife. Wright supports her argument with the text of the poem where the speaker, Thomas Hardy, cannot bear to think he might have loved "Otherwhere" nor have missed her "My life through." (Wright, 59)

Style:“The poem is in the style of a pastoral love-lyric" according to Gerhardus Van der Watt. He goes on to say in his dissertation that: "the poem becomes less directly pastoral after stanza 2, but the refrain constantly reminds the reader of the pastoral setting of her dwelling.”

(Van der Watt, 89) Finzi seems to have been attracted to this style of Hardy poetry or at least it seems to be one of the most common that he set to music.

Form: The structure of the poem is complicated according to Gerhardus Van der Watt. Van der Watt in his dissertation makes the following observations of Ditty:

“There are five stanzas each containing nine lines of unequal length, lines 2, 4 and 9 of every stanza being shortened. The final line of each stanza, ‘Where she dwells’, serves as a short refrain and forms a rhyming couplet with the penultimate line, which means that all five stanzas end with the same rhyming couplet structure. This feature establishes unity in the complex overall structure of the poem. The seventh line of each stanza contains internal rhyme (line 7 Sweet – meet, line 16 descry – I, line 25 strange – change, line 34 thought – nought, line 43 not – spot). The rhyme scheme is as follows: ababccd (internal rhyme) ee fgfghhiee etc. although there is a slight emphasis on iambic metre, the metre does not establish itself in any consistent pattern.”

(Van der Watt, 89)

Synthesis: With the first reading of the poem one might conclude Hardy's intentions to simply remind the reader that things in life seem to happen by chance but one can also detect a pessimistic undercurrent. Hardy has often been criticized for his pessimism and this poem seems to exemplify his pessimistic tone. Gerhardus Van der Watt writes in his dissertation: “The first two stanzas of the poem are purely pastoral, exalting his beloved and the splendid natural circumstances in which she lives. In the last three stanzas one is aware of an uneasiness on the part of the poet: he contemplates not having met her, that she may not have existed and that they met purely by chance. These sentiments cast a shadow of realism over the happy circumstances of their love-idyll. The title, ‘Ditty’, in terms of this discussion, seems inadequate to express the complexity of the context.” (Van der Watt, 89) The poem as was pointed out by Van der Watt seems to fall into two sections: the first being, a description of the pastoral setting and the second, a description of the pain one might have come to know had the two individuals not met. The poem seems to illustrate a young persons anxiety of a first love and yet the title of the poem doesn't seem to reflect what the poem is about. Perhaps the title tells one that Hardy thought his pondering of the situation to be frivolous and therefore it is a comment on his situation rather than framing the poem.

Published comments about the poem: James Osler Bailey records the following comments in his book about Thomas Hardy's Poetry: “The poem presents the rural isolation of St. Juliot, its tiny church (which Hardy, as architect’s assistant, had gone to St. Juliot to “restore”), and its rectory with “walls of weathered stone,” where Miss Gifford lived with her sister and brother-in-law. Hardy was attracted to Miss Gifford by her painting, her music, and most of all her vitality—her daring horsemanship along the picturesque cliffs of Cornwall. (Elfride in A Pair of Blue Eyes reflects the traits in Emma that attracted Hardy.) “ ‘She was so living,’ he used to say. In the poem ‘Ditty he called her ‘a Sweet,’ not a Beauty.” (Bailey, 60)

Criticism: Sarah Bird Wright records: "critics have called the poem derivative of the work of Robert Browning or the Dorset poet and clergyman William Barnes, but Hardy denied such influences."

(Wright, 59)

James Osler Bailey makes the following critical comments: “The poem, in which there is no pain, lacks the intensity of passion of the “she, to Him” sequence or the later “poems of 1912-13” concerned with Emma. It is characteristic of Hardy in meditating the slender chance that led him to her door: “What bond-servants of Chance / We are all.” Various critics have called this early poem derivative from Hardy’s reading: Duffin, that it “is in a Browning measure,” and Brennecke that William Barnes’s “ ‘Maid o’ Newton’ may well have provided its formal inspiration.” In his copy of Brennecke’s book Hardy wrote opposite this passage: “untrue.”

(Bailey, 60)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Wessex Poems

- Collection of 51 poems written by Thomas Hardy.

- Published in December of 1898 by Harper and Brothers.

- Hardy's first publication of his poems.

- Contains 30 illustrations made by Hardy.

F. B. Pinion categorizes the poems as a miscellaneous collection; ranging from ones strongly narrative to those that display Hardy's connection to Wessex. There are also poems that show Hardy's affinity for the Napoleonic War. (Pinion, 3)

"An anonymous reviewer for the Athenaeum believed the most successful poems were those that concentrated on Hardy's 'curious intense and somewhat dismal view of life.'" (Wright, 346)

"W. M. Payne, writing in the Dial, declared that the poems displayed 'much rugged strength and an occasional flash of beauty.' He believed there were several that almost persuaded him 'a true poet was lost when Mr. Hardy became a novelist.'" (Wright, 346)

Gerald Finzi set the following poems within this collection:

- Amabel (Before and After Summer)

- Ditty (A Young Man's Exhortation)

- I Look Into My Glass ( Till Earth Outwears)

- The Sergeant's Song [titled by Finzi as: Rollicum-Rorum] (Earth and Air and Rain)

Helpful Links:

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Musical Analysis

Composition date: 1928 (Banfield, 144)

Publication date: Copyright 1933 by Oxford University Press, London.

Copyright © assigned 1957 to Boosey & Co. Ltd. (Finzi, 134)

Publisher: Boosey & Hawkes - Distributed by Hal Leonard Corporation

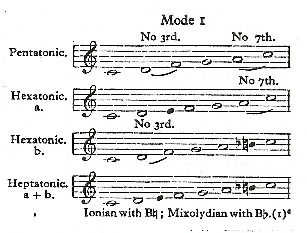

Tonality: At first glance "Ditty" seems to be in G Major but after realizing the leading tone or seventh scale degree is avoided most of the time the song appears to be in a hexatonic mode. Carl Rogers points out the use of pentatonic and hexatonic modes in his analysis of "Ditty." He supports his argument with a text written by Cecil Sharp in which folk songs are discussed. Dr. Rogers has also compiled a table in which the scale members of the melody are tabulated. From his analysis he concluded the tonic seems to drift between G and E. He references this point by using a table that shows how the dominant in the key of G is used less often than E. Therefore, Dr. Rogers feels the tonality hovers between G and the relative minor of E. To view his entire analysis please refer to: Tonality - Rogers. The use of several minor chords within the song gives one a modal feeling, this according to Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt. He concludes the song is in G major throughout and that the minor chords found within the piece simply flavor the song in a modal direction. To see Dr. Van der Watt's tonality analysis please refer to: Tonality - Van der Watt. Mark Carlisle has also made some comments affirming Dr. Van der Watt's opinion about the tonality. To view them please refer to: Comments on the Music - Carlisle.

Transposition: Currently unavailable.

Duration: Approximately two minutes and fifty-two seconds.

Meter: There is no meter signature indicated in "Ditty" instead Finzi uses bar lines to emphasize strong beats. There is a total of sixty-three measures in the song and of these forty-one have four beats, eleven have three beats, eight have five beats, and three have six beats. There doesn't seem to be a pattern and perhaps that is the reason Finzi chose to use no meter signature. The lack of a meter signature is not uncommon in Finzi's songs in fact he chose to use no meter signature in "The Comet at Yell'ham" and the beginning of "Shortening Days" within this song set. When Finzi doesn't use a meter signature or even bar lines in the case of "The Comet at Yell'ham," it doesn't seem to be strictly for musical purposes but rather to better serve the text. Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt has surmised the bar lines in "Ditty" exist for emphasis on particular words in the text and perhaps to aid the accompanist. To see Dr. Van der Watts comments in their entirety please refer to: Metre - Van der Watt. Mark Carlisle in his analysis of "Ditty" concludes the frequent shifts in meter give the song a feeling of "disjunction" but at the same time generates interest because one is unable to predict the next meter shift. To see Dr. Carlisle's comments please refer to: Metrical Ingenuity - Carlisle.

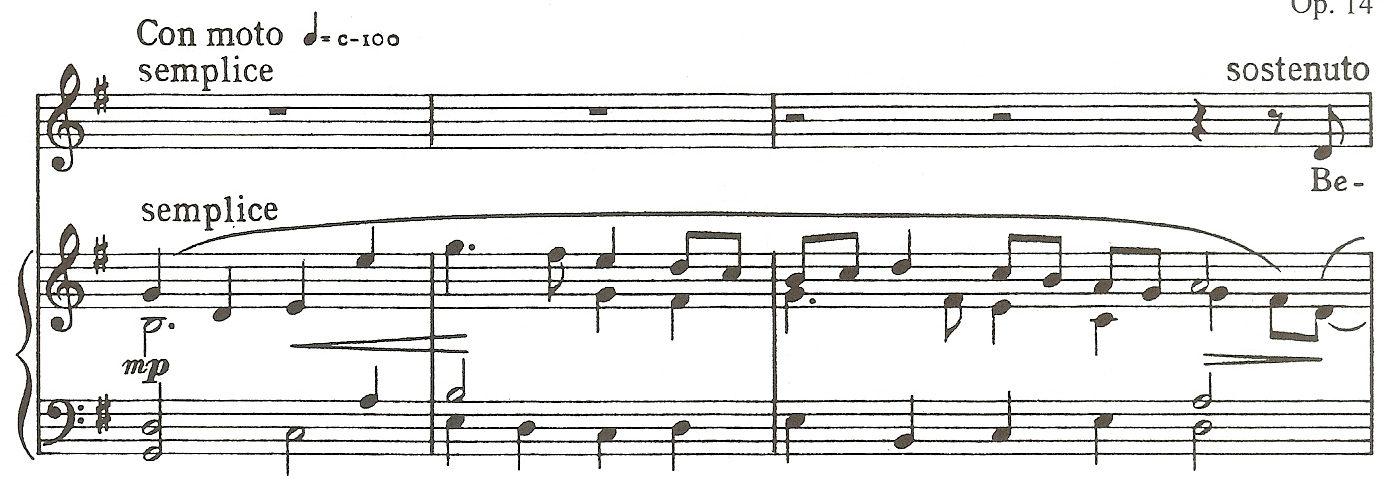

Tempo: The score indicates Con Moto with the quarter note equalling c. 100. For additional comments about the tempi within the song please refer to: Speed - Van der Watt.

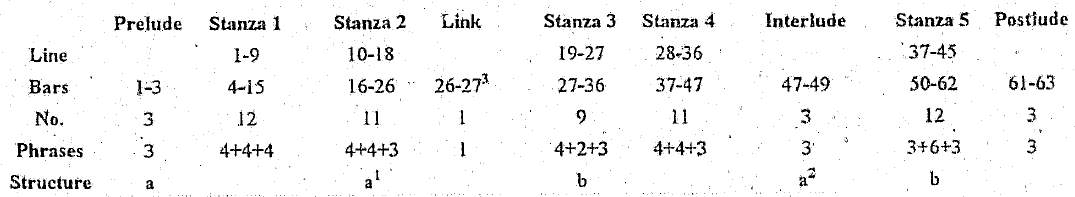

Form: Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt, in his dissertation, describes the structure of the song as "Varied Strophic." When one looks at the score, there are similarities between stanzas 1, 2, and 4 as well as stanzas three and five but the use of the words varied strophic implies rather exact copies of the stanzas and that doesn't seem to be the case. Mark Carlisle also uses the term "varied strophic" in his description of the form. One may conclude from their definition of the term of "varied strophic" that it is permissible to have two different melodies for the verses and then simply modify them slightly. Dr Van der Watt has prepared a chart that depicts the melodic curve of each stanza and this should help illustrate the similarities as well as dissimilar melodic material. To view it please click on: Melodic Curve - Van der Watt. One could describe the song as through-composed but that doesn't seem to be accurate as well. It would however reflect that the strophes are not similar. A compromise may be best in this situation and therefore, this author, will describe "Ditty" as A B C B¹ C¹/varied strophic. Michael R. Bray, in his thesis comments that the form for the vocal line is ABCBC but the accompaniment is ABABA. To view Dr. Bray's comments please refer to: Form - Bray. To view Dr. Van der Watt's analysis of the structure in which he illustrates the nine different sections of the song please refer to: Structure - Van der Watt. To view Dr. Carlisle's comments please refer to: Comments on the Music - Carlisle.

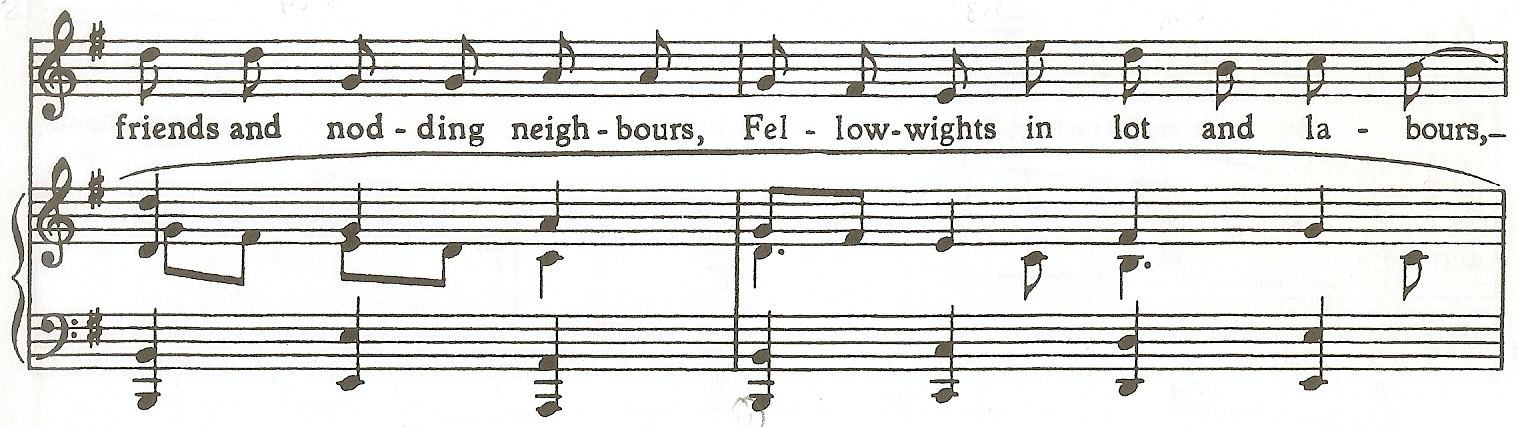

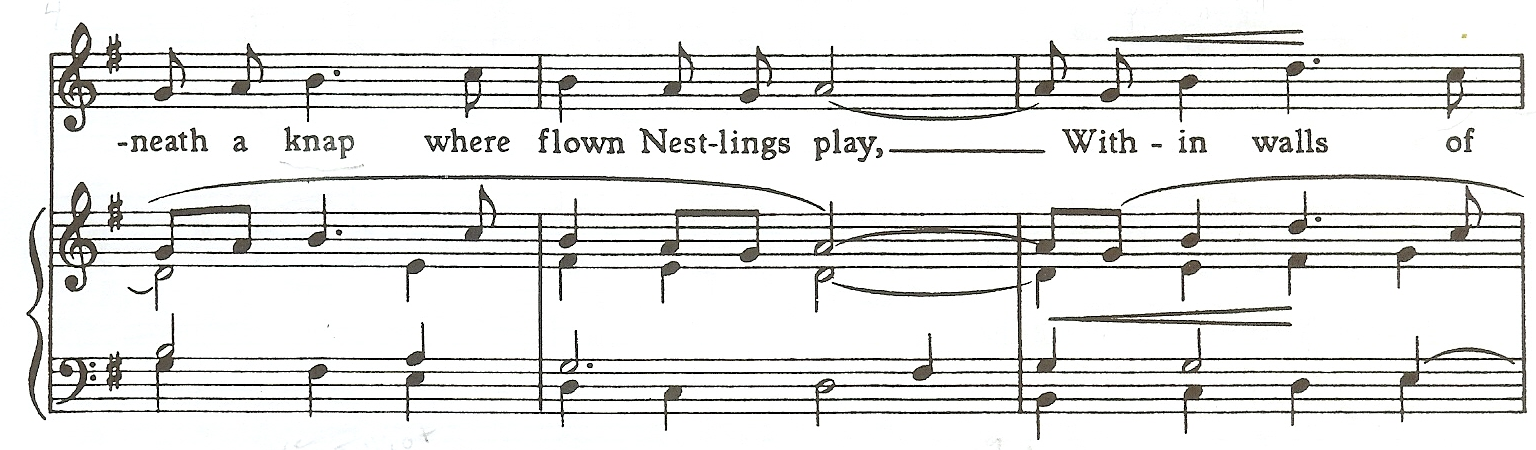

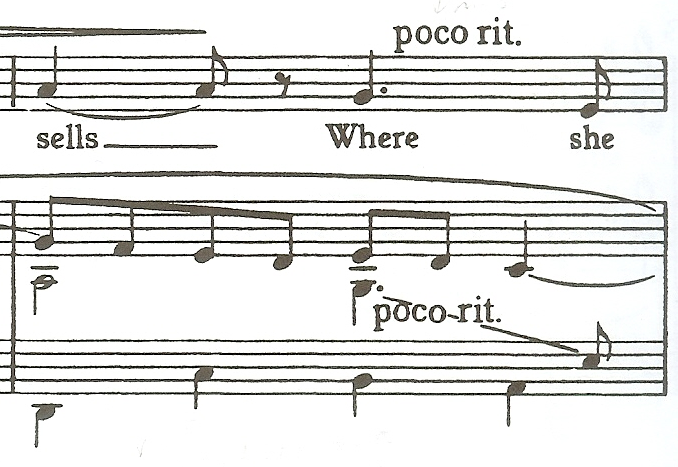

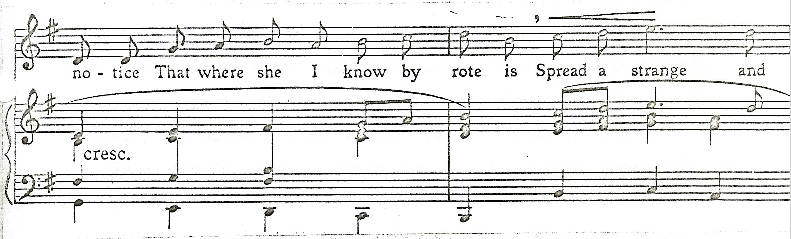

Rhythm: There are no particular rhythms that are difficult to sing within "Ditty" and Finzi's setting seems less creative than usual. His settings normally parallel speech rhythms closely but in "Ditty" his predominant use of the eighth-note detracts from the lyrical language of the text at times. An example of these running eighth-notes occurs in the second stanza between measures twenty and twenty-two. There one will find fifteen eighth-notes in succession. See Example 1 below.

Example 1 "Ditty" measures 22-23. (Finzi, 136)

Finzi always struggled more with songs of a quicker tempo and "Ditty" falls into this "quicker" category even though the tempo is not terribly fast. The tempo may be partially to blame but another possible reason for his less than stellar text setting may come from the length of the poem and the use of recurring thematic material. According to several Finzi authorities including Stephen Banfield, Diana McVeagh and his son, Christopher Finzi, Gerald Finzi would compose fragments from ideas that would come to him after reading a line of the poetry. With this in mind coupled with the length of the poem one can see how the song could have become unruly and difficult for Finzi as he attempted to assemble the many fragments. One alternative to him may have been to utilize eighth-notes to bind together his melodic ideas. One must also consider this song is relatively early in Finzi's career and his skills were not as finely honed. The song does show some signs of Finzi's ability to set the text cleverly and Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt has created a small table that illustrates these settings. To view the settings please refer to: Interesting Settings - Van der Watt. Dr. Van der Watt has also painstakingly analyzed the rhythmic motives within the song and to view them please use the link: Rhythmic Motives - Van der Watt. Michael R. Bray, has also commented extensively on the rhythmic choices Finzi utilizes in this song as well as the motivic material. To view his comments please refer to: Rhythm - Bray. "Ditty" has also been subjected to a rhythmic duration analysis. This should be helpful to those interested in the number of occurrences a particular note value was used and the strophe in which it occurred as well as the total number of occurrences within the entire song. To view the results please refer to: Rhythm Duration Analysis.

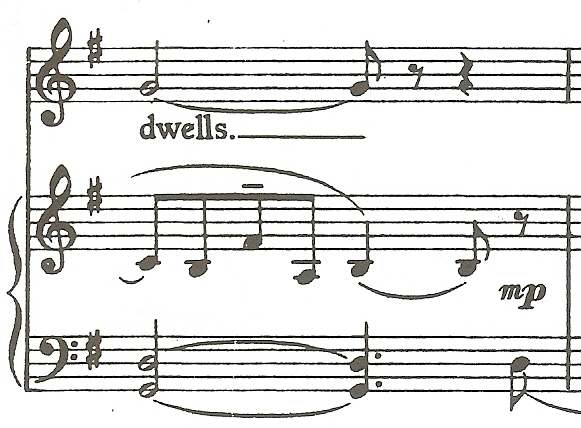

Melody: Finzi's melodic characteristics for the vocal line typically utilizes step-wise motion or small leaps with occasional larger leaps for emphasis of text; "Ditty" fits this profile primarily. One slight alteration to the normal Finzi practice occurs in measure twenty-four where the melody takes on a down up down up down up motion which is not characteristic of Finzi's song writing. See example 2.

Example 2 "Ditty" measure 24. (Finzi, 136)

Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt's analysis of the song is quite extensive and to see his comments about the melodic material please refer to: Melody - Van der Watt. "Ditty" has also been subjected to an interval analysis for the purpose of discovering the number of occurrences specific intervals were used and also to see the similarities if there were any between stanzas. Only intervals larger than a major second were accounted for in the interval analysis, to see a complete description of the results of the interval analysis please see refer to: Interval Analysis.

Texture: The texture is homophonic and ranges from three to five parts in the piano accompaniment. When the accompaniment is rather sparse "Ditty" takes on a more folk or "Country Air" feeling. In Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt's comments about the texture, he created a chart describing the texture. This table could be interesting to those that would like to know the number of occurrences specific types of texture were used. To view Dr. Van der Watt's comments please refer to: Texture - Van der Watt.

Vocal Range: The vocal range spans the interval of a perfect eleventh. The lowest pitch is the D below middle C and the highest pitch is the G above middle C. The vocal line does not extend above the E above middle C in the first three stanzas and even after that there are only eight occurrences of pitches above the E in the remaining two stanzas.

Tessitura: The song has a tessitura of an octave from the E below middle C to the E above middle C. A pitch analysis was performed for the purpose of accurately determining the tessitura and for the complete results please refer to: Pitch Analysis.

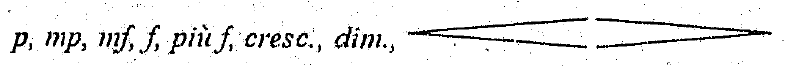

Dynamic Range: Finzi uses a variety of dynamics throughout the song and they range from piano to piu forte with frequent use of crescendo and decrescendo. There is more attention to detail in the piano dynamics than the vocal line but there are occasional crescendo and decrescendo marks in the vocal line as well. For additional information please refer to: Dynamics - Van der Watt. Once there you will find Dr. Van der Watt's comments on the dynamics and also a table that he has assembled containing all of the dynamics indicated throughout the song.

Accompaniment: The accompaniment ranges from chordal to more active movement. It is not difficult but there are moments in which it is more complicated than others. For example there are frequent indications of dynamics that require attention. Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt has made some comments about the accompaniment and these may offer some further assistance. To view them please refer to: Accompaniment - Van der Watt. Carl Rogers has referenced measure forty-two for a strong dissonance and he comments on this in his thesis. To view his comments please refer to: Accompaniment - Rogers.

Pedagogical Considerations for Voice Students and Instructors: This is one of the longest Thomas Hardy poems Finzi set to music and as such one will find interpreting the text and then declaiming it to the audience more difficult than any other aspect of the song. Good breath management will be extremely important as one negotiates the text. One will also find the breath key to managing the subtle nuance necessary to bringing life to this song. For example, the second-half of the second stanza beginning with "But to friends and nodding neighbours, Fellow-wights in lot and labours, Who des-cry the times as I, No such lucid legend tells Where she dwells." In these lines one could possibly slip in to a "patter" like declamation having the effect of making cheap the text. An exercise in reciting the poem could possibly assist one in finding more nuance in this particular stanza and would most assuredly help in the declamation of the text once one sings the phrase. The poetry of Thomas Hardy is not easy to understand for most and therefore time spent with the poem discovering its treasures and nuance will greatly assist in the eventual performance of this song.

Dr. Mark Carlisle records in his dissertation the following observations and advice: "This song presents few musical problems for the performer outside of proper and expressive text declamation. The very character and nature of the piece requires an honest, direct approach to its interpretation; anything more would create an overly affected performance. The only tempo marking is that of [quarter note] - c. 100 (Con moto) at the beginning, although the expressive marking of semplice is also indicated. Other expressive markings throughout the piece are those of ritardando that highlight natural moments for slight rubato, and a poco tenuto in measure 45. These are all quite appropriate and would present no difficulties for reasonably sensitive performers. Most of the dynamic markings in either accompaniment or vocal line are adequate for the needs of this piece; no extensive dynamic contrast is required or necessary. However, performers should take special care to observe the piano from measure 29 to 31; this is a poetic aside, and should be treated in a slightly different fashion than the rest of the text." (Carlisle, 105-6)

"Breath marks for the singer, on the other hand, do not seem particularly appropriate in this song. For instance, a full breath does not seem necessary after the word "be" in measure 29; an expressive lift would be much more appropriate, allowing both singer and accompanist a longer and more musical sense of phrasing. The same could be said of the breath mark for the singer in measure 53. Finally, while the breath mark in measure 33 after the word "is" indicates a truly important moment requiring a textual break, a lift at this point followed by a full breath after the word "change" in measure 34 would be more appropriate. The increased length of the vocal phrase would not in most cases cause a performer undue difficulties, and it would allow a smoother, more natural breath than the one indicated." (Carlisle, 106)

"The technical demands of this piece are not extensive; it has a very short range, little more than an octave, and the tessitura should be quite comfortable for most young tenors. There is certainly a need for a good sense of rhythm, but the overall character of the song is not complex, and its emphasis on a moving lyricism would most likely be quite attractive to a young singer. The most difficult aspects of this piece are the complexity of the poetry, and how to declaim the text in as natural and unaffected a manner as is possible given Finzi's style of text setting. Neither of these is insurmountable for a young tenor if he has the patience and guidance necessary to fully understand the poem. Most graduate-level tenors should be able to handle this piece with little difficulty, and while it is somewhat more problematic for an undergraduate, given adequate literary study, its relative technical and musical ease would make it even at the level an excellent recital selection." (Carlisle, 106-7)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Below one will find excerpts from unpublished dissertations and theses. The excerpts should provide a more complete analysis of Ditty for those wishing to see additional detail. Please click on the link or scroll down.

Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

Michael R. Bray - An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

TABLES

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Audio Recordings

The Songs of Gerald Finzi to Words by Thomas Hardy

|

|

|

|

Gerald Finzi Song Collections |

|

|

|

The English Song Series - 16 |

|

|

|

Song Cycles for Tenor & Piano by Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

Songs by Britten, Finzi & Tippett |

|

|---|---|

|

|

Songs of the Heart: Song Cycles of Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

The following is an analysis of Ditty by Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt. Dr. Van der Watt extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on October 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated November 1996, is entitled:

The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt comes from Volume II and begins on page eighty-seven and concludes on page eighty-nine. To view the methodology used within Dr. Van der Watt's dissertation please refer to: Methodology - Van der Watt.

1. Poet

Specific background concerning poem:

"The poem appeared in Wessex Poems (1898) and is dated 1870. The subtitle shows that the poem was specifically written for his first wife, Emma Lavinia Gifford, within months of their first meeting. Florence Hardy, his second wife, writes in "Life" published in 1930 that, "In his leisure he seems to have written the "Ditty" ...inscribed with Miss Gifford's initials"."

(Florence Hardy, 101)

(Van der Watt, 87)

"Martin Seymour-Smith suggests the following:"

(Van der Watt, 87)

"In this period [having returned to London after the first visit to Cornwall during which he met Emma] he wrote the 'Ditty (ELG)' to Emma, a poem which, when he published it in Wessex Poems in 1898, she did not by then consider sufficient compensation for other poems to other women, and she complained bitterly...It has a somewhat dutiful air, written from the feeling that it was Emma's due from her poet." (Seymour-Smith, 112) (Van der Watt, 87) |

2. Poem

"Thomas Hardy writes this simple song to his newly met love, Emma Gifford who lives an isolated life, far from the bustle of town, in a remote part of Cornwall. Everything in these idyllic circumstances reminds him of her. He immediately comments that he regards her and the natural surroundings in a different light from the ordinary folk around, simply because he is in love. Hardy's next thought, typically, is what it would be like if they had never met: their lives would be, "Like the drying of the wells". He reproaches himself by saying that even to entertain the thought of her not existing, is too painful to contemplate. In the final stanza he marvels at the chance-like circumstances of their meeting: he goes on an ordinary architectural business excursion to draw some plans for the restoration of the church as St. Juliot, where she happens to be staying with her sister, at the time, who is the wife of the vicar of the church. The focus of the poem is the refrain, "Where she dwells" and the beloved is praised indirectly, because she makes the place so special."

(Van der Watt, 88)

"The poem is in the style of a pastoral love-lyric. The poem becomes less directly pastoral after stanza 2, but the refrain constantly reminds the reader of the pastoral setting of her dwelling."

(Van der Watt, 89)

"The poem has a fairly complicated structure: There are five stanzas each containing nine lines of unequal length, lines 2, 4 and 9 of every stanza being shortened. The final line of each stanza, "Where she dwells", serves as a short refrain and forms a rhyming couplet with the penultimate line, which means that all five stanzas end with the same rhyming couplet structure. This feature establishes unity in the complex overall structure of the poem. The seventh line of each stanza contains internal rhyme (l. 7 Sweet - meet, l. 16 descry - I, l. 25 strange - change, l. 34 thought - nought, l. 43 not - spot). The rhyme scheme is as follows: ababccd (internal rhyme) ee fgfghhiee etc. Although there is a slight emphasis on iambic metre, the metre does not establish itself in any consistent pattern."

(Van der Watt, 89)

"The first two stanzas of the poem are purely pastoral, exalting his beloved and the splendid natural circumstances in which she lives. In the last three stanzas one is aware of an uneasiness on the part of the poet: he contemplates not having met her, that she may not have existed and that they met purely by chance. These sentiments cast an shadow of realism over the happy circumstances of their love-idyll. The title, "Ditty", in terms of this discussion, seems inadequate to express the complexity of the context."

(Van der Watt, 89)

Setting

1. Timbre

VOICE TYPE/RANGE

"The song is set for tenor and the range is a perfect eleventh from the first D below middle C."

(Van der Watt, 89)

ACCOMPANIMENT CHARACTERISTICS:

"The upper limit of the piano employed in this song is the second G above middle C while the lower limit extends to the third E below middle C. In only 37% of the bars no ledger line is used below the bass clef stave which means that the middle to lower register is favoured. A four-part piano texture dominates and with the middle sonority a clear, fairly neutral atmosphere is established. There are no indications of pedalling, the implication being that it is the performer's responsibility to apply the pedal as needed. Legato touch is the only indication of articulation apart from a small number of portamento accents (b. 15, 17, 18, 31, 44, 57, 62) and a single stronger accent (>) on bar 42³. The accent in bar 42 is a significant one due to the harmonic treatment in relation to the text: a major-minor chord (B-D-D#) is used on the word "smart" and is the only bold dissonance in the entire song of 63 bars."

(Van der Watt, 89)

"The atmosphere suggested by the piano part is consistent throughout. There is no emotional upheaval, extreme excitement or depth of despair. There is no modulation or even secondary dominant and only a single chromatic note, discussed in the previous paragraph. The atmosphere is calm, uncomplicated (b. 1 semplice), reflective and at most, pensive."

(Van der Watt, 89)

2. Duration

"The textual metre is irregular and Finzi follows suit, not committing himself to a time-signature. He provides barlines merely to assist the pianist to perceive the strong beats. The result is that 41 bars are in common-time, the most prominent metre by far, 11 bars in simple triple metre, 8 bars in 5/4 and 3 bars in 6/4. There are 31 changes of metre, most of which occur for the sake of placing a particular word in a place of prominence (b. 8 Far, 14 Sweet, 17 Here, 18 She, etc.)."

(Van der Watt, 90)

Rhythmic motifs

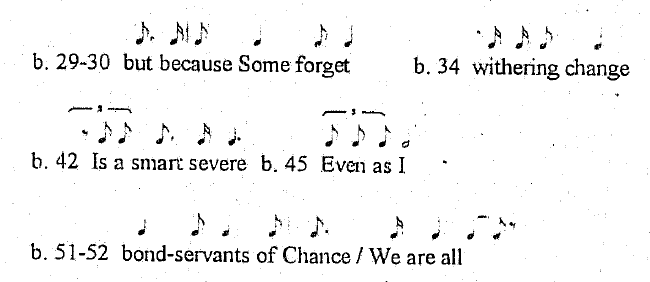

"The most prominent motif (motif 1) consists of four quavers [eighth notes] and occurs 33 times in the piano part and 22 times in the vocal part. Apart from the obvious function of creating unity, this motif is also largely responsible for the forward movement in the song (it appears the first time in bar 3 and the last time in bar 62). The directly augmented version of this motif (motif 2), consisting of four crotchets [quarter notes], occurs only in the piano part, 29 times (b. 1, 2, 3, 6(2), 9, 10, 14, 19, 22, 23(2), 24, 26, 27, 28, 30, 32, 33, 34, 43(2), 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 51, 56, 58 and 59). Motif 2 is also the beat-unit on which the metre of the song is based, as is the speed of the harmonic rhythm. Motif 3 occurs only eight times but this at intervals during the song due to the varied strophic form, thereby gaining significance: a dotted crotchet and quaver (b. 2, 4-5(2), 8(2), 27, 48 and 57). There are also some variations on the this motif in bars 24 - 25 and 50. The final motif which establishes itself (motif 4) is the rhythmic and melodic setting of the refrain, "Where she dwells" (b. 14-15, 25-26, 35-36, 46-47, and variant 60-62)."

(Van der Watt, 90)

Rhythmic activity vs. Rhythmic stagnation

"The rhythmic activity is dictated by the natural flow of crotchets and quavers and is interrupted only four times with longer values: bars 17-18 on the text, "Here is she," bar 38 on, "Loved as true," bar 45 on, "Even as I" and bar 56 on "dells." The rhythmic activity is fairly uniform throughout."

(Van der Watt, 90)

Rhythmically perceptive, erroneous and interesting settings

"The following words have been set to music perceptively:"

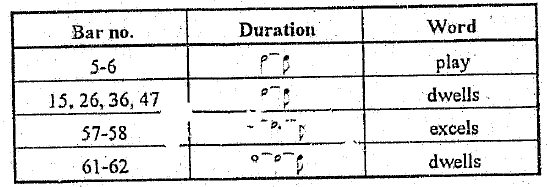

(Van der Watt, 90)

Lengthening of voiced consonants

"The following words containing voiced consonants have been rhythmically prolonged in order to make the word more singable:"

(Van der Watt, 90-1)

"The tempo indication is Con Moto [with a quarter note equalling 100]. This suggests a swiftness of movement which suit content of the poem. Tempo deviations are listed below:"

Bar no. |

Deviation |

Bar no. |

Return |

Suggested reason/s |

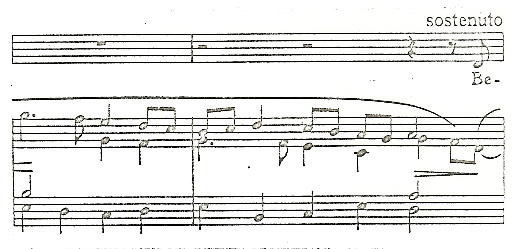

3 |

sostenuto |

Stanza 1 - emphasis on opening |

||

14 |

poco rit. |

16 |

a tempo |

End of stanza 1 - emphasis |

35 |

poco rit. |

37 |

a tempo |

End of stanza 3 - emphasis |

43-45 |

rit. poco tenuto |

47 |

a tempo |

Emphasis, dramatic pause |

56 |

rit. |

57 |

a tempo |

Extend climax- emphasis |

59 |

poco rit. |

60 |

ritardando |

Anticipate end |

"In bars 24-25, anticipating the instincts of musical performers, the composer specifies that there should be no loss of tempo at the end of stanza 2 (senza rit.)."

(Van der Watt, 91)

3. Pitch

Intervals: Distance distribution

Interval |

Upwards |

Downwards |

Unison |

(30) |

|

Second |

85 |

68 |

Third |

19 |

20 |

Fourth |

8 |

3 |

Fifth |

2 |

11 |

Sixth |

3 |

0 |

Octave |

2 |

2 |

(Van der Watt, 91)

"There are 30 repeated pitches (or 12% of the total number), 119 rising intervals (or 47%) and 104 falling intervals (or 41%). The smaller intervals (a third and smaller) account for 222 intervals (88 of the total number) while the larger intervals (fourths and larger) account for 31 (or 12%). It is clear from these statistics that the song is vocally sympathetic in the extreme. The interval of a third (rising and falling) and the falling perfect fifth have relatively high recurrences and as such, help to create melodic unity in the song. In a vocally conservative context, all leaps gain more significance. The following table is a summary of specific settings:"

(Van der Watt, 91)

Interval |

Bar no. |

Word/s |

Reason/s |

5th up |

7-8 |

stone Far |

Reinforce meaning |

5th down |

17-18 |

is she |

Emotional content reinforced |

8th up |

22 |

wights in |

Change of register |

8th down |

23 |

as I |

Change of register |

8th down |

24 |

lucid |

Reinforce meaning |

5th down |

28 |

I was |

Emphasis |

5th down |

31 |

if none |

Emphasis |

5th down |

38 |

as true |

Emotional content reinforced |

6th up |

38 |

through, Had |

Emphasis |

5th down |

45 |

as I |

Emotional content reinforced |

5th down |

50 |

her glance |

Emotional content reinforced |

6th up |

51 |

what bond |

Emphasis |

8th up |

54 |

errant |

Reinforce meaning |

(Van der Watt, 91-2)

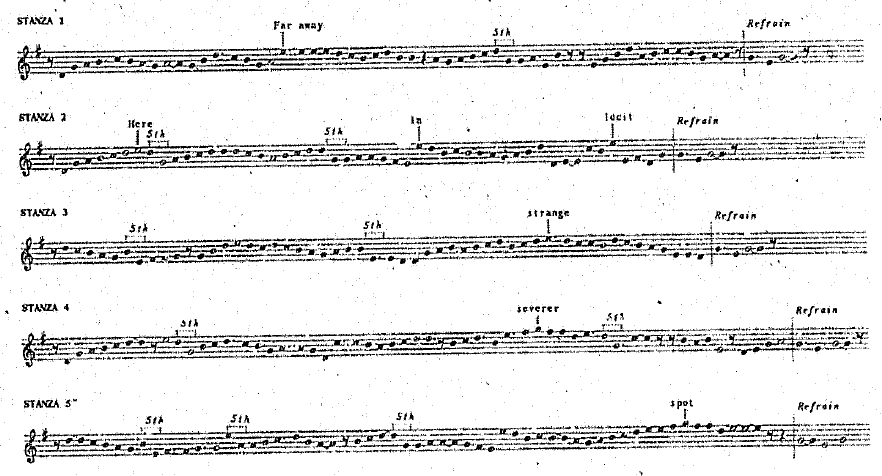

"A melodic curve of the vocal line is represented below. Certain words are indicated to show the relationship between the melodic curve and the meaning of the text:"

(Van der Watt, 92)

(Van der Watt, 92)

Climaxes

"The two vocal climaxes are given below:"

Bar no. |

Pitch |

Word |

43 |

G |

severer |

56³ |

G |

spot |

(Van der Watt, 92)

Phrase lengths

"Breathing marks are occasionally inserted by the composer. A number of others are also provided:"

Stanza 1 b. 4-15 |

Breathe at b. 6¹ and 7⁴ (others are indicated by rests) |

Stanza 2 b. 16-26 |

Breathe at b. 18², 20², 23¹, 24¹ |

Stanza 3 b. 28-36 |

Indicated (b. 29⁴, 31², 33¹) also b. 35¹ |

Stanza 4 b. 37-47 |

Breathe at b. 39³ (others are indicated by rests) |

Stanza 5 b. 50-62 |

Breathe at b. 51², Indicated (b. 55²), 56¹ |

(Van der Watt, 92-3)

"The song is in G major throughout. There are no modulations and only a single chromatic alteration in bar 42: D sharp is used against D natural and B, resulting in a major-minor chord built on B. The equivalent word in the text is "smart" and the chord furnished with an accent (>) sets this textual detail in a most effective way. The extensive use of the three minor chords: iii, vi and ii and their inversions creates a modal sense in the song: bars 11³ - 12⁴, 23⁴- 24², 26³ - 27², 34³-⁴ and 47³ - 48²."(Van der Watt, 93)

HARMONY AND COUNTERPOINT

"Diatonic quartads (1₇, ii₇, IV₇), in all inversions are used frequently. Triads in "unorthodox" second inversions are used for the sake of creating dissonance in a largely tonal context."

(Van der Watt, 93)

Non-harmonic tones:

"A further means of creating dissonance is the extensive use of accented non-harmonic tones. The suspensions are numerous and very much part of Finzi's sound palette. The accented passing note, however, takes a very prominent role in the song: Bars 5²(A), 10²(A), 23²(A), 28⁴(B), 29²(F sharp), 33²(EGC), 34³(C), 34⁵(B), 35¹(G), 55⁴(EAC), 59²(A), 61²(C) and 61⁴(E). A conspicuous escape tone occurs twice (b. 15² and 62²) where the leading note (F sharp) in the alto part of the piano treble clef sounds against a sustained tonic directly above it. This escape tone is furnished with a portamento accent in both cases. In the parallel place (b. 36²) a changing note pattern is used."

(Van der Watt, 93)

Harmonic devices:

"The use of a major-minor chord on B in bar 42 has already been discussed. There are no significant pedalpoints in the piano part but there are two instances of a prolonged note in the vocal part: bars 57 - 58(E) and 61 - 62(G). Both of these enhance the dissonance and dramatic effect close to the end of the song."

(Van der Watt, 93)

Counterpoint:

"There is a lot of free counterpoint in the piano part but only small four-note snatches of imitation: (b. 16, 36-37, 45, 58 and 59-60)."

(Van der Watt, 93)

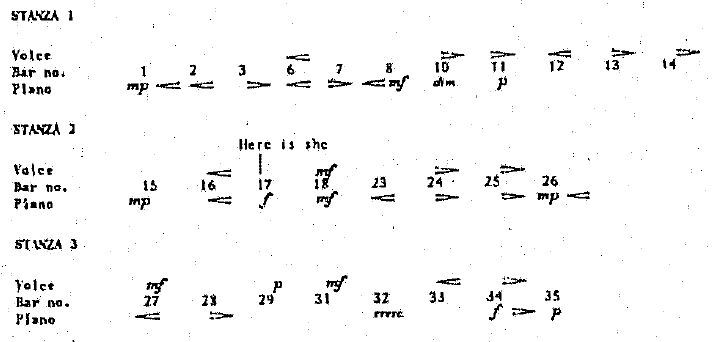

"There are separate dynamic indications for the voice. Loudness variation is given in the following summary:"

(Van der Watt, 93-4)

(Van der Watt, 93-4)

FREQUENCY

"There are 48 indications in the piano part and 28 in the vocal part in the 63 bars. This means that on average 76% of the piano part bars and 44% of the vocal part bars contain an indication. Where there are no indications for the vocal part, piano part indications should be followed."

(Van der Watt, 94)

RANGE

"The lowest level indication is p (b. 10, 29, 35, 47, 60) and the highest level indication piu f (b. 56). The emphasis is on lower dynamic levels."

(Van der Watt, 94)

VARIETY

"The indications used are:"

(Van der Watt, 94)

(Van der Watt, 94)

DYNAMIC ACCENTS

"There is only one strong dynamic accent namely on bar 42³(>). The accent occurs on the word "smart" and has already been discussed. Seven portamento accents occur in the piano part and are merely used for mild dynamic emphasis."

(Van der Watt, 94)

"The density varies loosely between three and seven parts including both piano and voice. The thickness of the piano part is represented in the following table:"

No. of parts |

No. of bars |

Percentage |

2 parts |

1 |

1.5 |

3 parts |

19 |

30 |

4 parts |

29 |

46 |

5 parts |

13 |

21 |

6 parts |

1 |

1.5 |

"The three- and four-part texture types dominate in the song. The occurrence of a five-part piano texture is limited to specific bars (b. 17-231, 38-42, 44-45, 52, 58) and serves to emphasize and intensify the emotional content of the adjacent text (eg. b. 17-21: "Here is she!" Immediately following the text, "Like a drying of the wells" the texture thins out to a two-part piano setting in bar 35. This subtle reinforcement of the text through the texture of the music is confirmed in bar 57 where a six-part texture accompanies the word "excels," immediately following a vocal climax in bar 56."

(Van der Watt, 94)

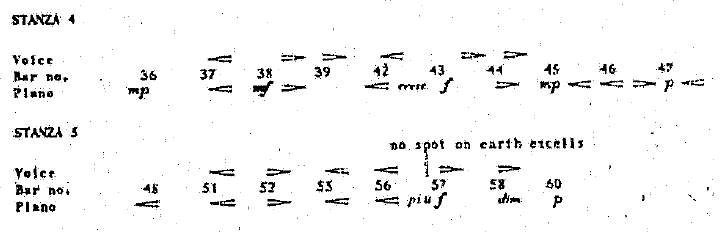

"The structure of the song is represented in the following table:"

(Van der Watt, 95)

(Van der Watt, 95)

"The song has a varied strophic construction. Stanzas 1, 2 and 4 are similar, and 3 and 5 are similar. Each stanza except the final one has an exact repetition of the vocal refrain. "Where she dwells." In the final stanza the rhythm is varied while the melodic material remains."

(Van der Watt, 95)

7. Mood and atmosphere

"The mood and atmosphere of the song remain fairly consistent throughout. A somewhat pensive but almost neutral mood is suggested mainly by the accompaniment but also by the largely stepwise vocal line. The only slightly harsh moment occurs on the word "smart" b. 42³)."

(Van der Watt, 95)

General comment on style

"The song is harmonically confined to tonal and slightly modal practices. There is only one chromatic note in the song which in the context, becomes quite prominent. Non-chordal tones used on the beat create most of the dissonance while several chords are furnished with sevenths and used in unconventional second inversion positions. The song is extremely voice friendly (88% smaller intervals) and has an interesting metric make-up: no time-signature is used and bar lines indicate the important passages in the text."

(Van der Watt, 95)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Ditty by Mark Carlisle. Dr. Carlisle extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 7th, 2010. His dissertation dated December 1991, is entitled:

Gerald Finzi: A Performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and Piano to Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page ninety-eight and concludes on page one hundred seven.

""Ditty" was published in 1898 as part of Wessex Poems. Most poems included in this set were written in the 1860's, and offer verbal sketches of the pastoral life as Hardy saw and experienced it. Hardy himself drew thirty-one illustrations in the first edition of these poems that depict the scenes he described. "Ditty" was written in 1870 soon after his chance encounter with Emma Gifford, with whom he promptly fell in love. He inscribed her initials on his manuscript, indicating that this poem was clearly an attempt to describe his thought upon meeting his first wife. The poem describes the village of St. Juliot and its tiny church where Hardy, an architect's assistant, had been sent to oversee restoration and alterations. The "weathered walls" of which Hardy speaks is the rectory where Emma lived with her sister and brother-in-law."

(Carlisle, 98)

"This poem, like "A Young Man's Exhortation," is also somewhat difficult for those unfamiliar with Romantic English poetry. While the sentiment expressed in these verses is a common one, the language used is somewhat archaic and esoteric in comparison to that used today. While a full translation of the whole poem is not in this case necessary, several terms still need definition: "knap" - the crest of a hill; "flown Nestlings" - birds that have just left the nest; "firstling" - first-born; "fellow-wights" - fellow human beings; "descry" - discern, discover; "feign" - to give a false appearance; "a smart severe" - a painful emotional cut; "nought" - nothing; "out-skirt" - go around."

(Carlisle, 98-9)

"The fourth stanza of the poem is, however, particularly difficult to understand so a modern, paraphrased version of the verse is again offered:"

(Carlisle, 99)

"To realize that I might have kissed and loved |

"'Ditty' represents one of the longest, but at the same time compositionally simplest, of the songs in this cycle. The poem of five stanzas is set in varied strophic format with unusual consistency of melodic, harmonic, and textural elements. A brief, three-note motive is used to underscore the words 'where she dwells' that conclude each stanza, serving as the primary means of unification throughout the song. The opening key of the song, G major, remains in place from beginning to end, with little if anything that could be construed as harmonically imaginative or unusual. In fact, with only the possible exception of the third song in this cycle, 'Budmouth Dears,' it is the least harmonically complex song of this entire cycle."

(Carlisle, 99)

"It is also a prime example of Finzi's overwhelming penchant for composing in a syllabic style that can at times become cumbersome when used, as in this case, with a particularly complex poem and moving tempo. Nevertheless, interest is maintained primarily through the use of the following: 1) subtle but consistent meter changes; 2) a tempo that keeps the energy of the song relatively high; 3) a melodic shape that has variety but at the same time enough emphasis on conjunct motion not to make declamation of the text overly clumsy; and, 4) the previously mentioned three-note motive containing one simple interval change of a minor third, as well as a second, two-measure motive heard in the accompaniment only at the beginning of the first, third, and fifth musical sections."

(Carlisle, 99-100)

"The length of the piece, sixty-three measures in all, is comparatively long, but due to the quickly moving tempo the actual duration of the song is not as lengthy as some others. The five sections are divided in the following manner, with overlaps indicated in parentheses: section one, measures 1-15; section two, measures 16-25(26); section three, measures 26-36; section four, measures 37-46(47); and section five, measures 47-63. Sections one, three, and five all begin with the same motive in the accompaniment as previously mentioned, while the second and fourth sections begin somewhat differently. However, musical changes are more for the sake of variety than substance, so the basic musical character from beginning to end is very similar and consistent. Therefore, discussion will center on those general musical elements that are important throughout the song, rather than a section by section analysis."

(Carlisle, 100)

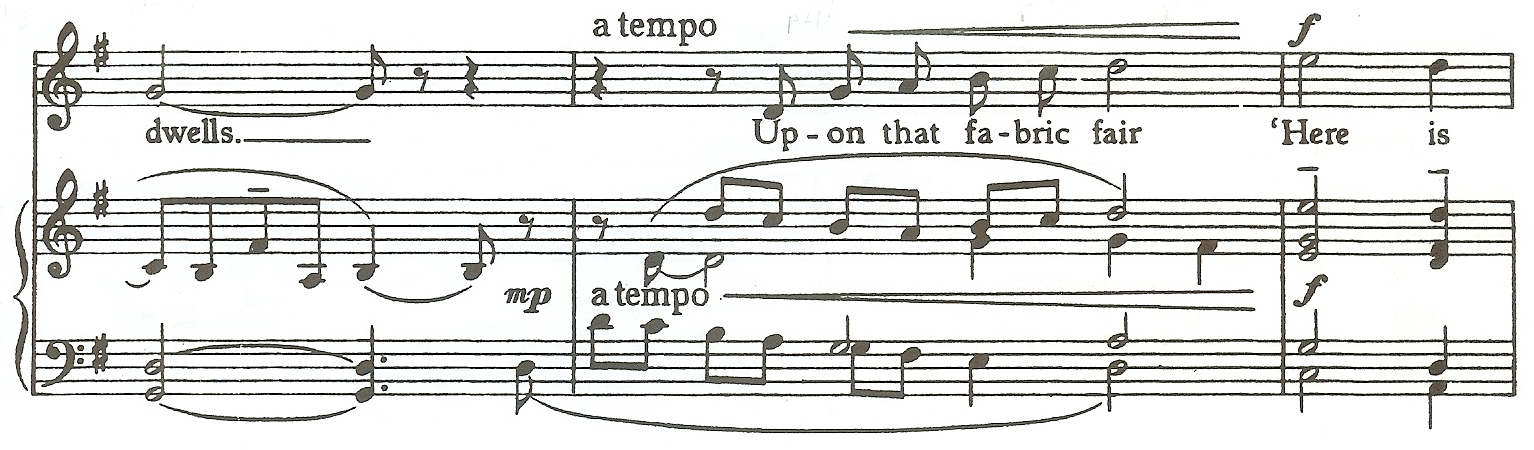

"The first important factor is metrical ingenuity. No meter is ever indicated in this piece; measure lengths are simply changed whenever necessary in order to facilitate poetic phrasing. For instance, within the first six measures of the piece there are three separate, unmarked meter changes. Measures 1 and 2 are in 4/4, followed by a change in measure 3 to 6/4. Measure 4 again changes to 3/4, and the third change within these six measures occurs in measure 5 by a return to the opening 4/4. These abrupt and frequent unmarked meter changes, as seen in Example 11, occur throughout the song, lending the entire piece a certain rhythmical 'disjunction' that is at times unsettling, but also quite interesting."

(Carlisle, 101)

"Example 11. 'Ditty,' measures 1-6." (Carlisle, 101) |

"This 'disjunction' occurs not only from measure to measure, but also from section to section. Although the form of the song is best analyzed and heard as varied strophic, each of the sections is slightly different in length from its predecessor. This is certainly necessary to accommodate the differing lengths of the poetic stanzas, but still provides yet another element of metrical interest."

(Carlisle, 101-2)

"Metrical changes are also the only significant difference between the five sections. Sections one, three, and five begin with a two-measure motive in 4/4, while the second and fourth sections begin with one measure in 6/4 followed by two in 3/4. This alone is not enough to create a uniqueness about sections two and four that would distinctly set them apart, but it does add enough variety during the changes from section to section to keep excessive rhythmical blandness from entering the musical picture."

(Carlisle, 102)

"The next important factor concerns two motives, one of which recurs often, that together provide the most obvious means of musical unification during the song. Motive one is heard in the right hand of the accompaniment in the first two measures of the song (see Example 11). This two-measure melodic fragment returns in exactly the same structure each time, first in measure 26 and then again in measure 47. Each motivical return signifies the beginning of a new section, and while it does not begin all five sections, its return at the beginning of sections three and five does allow the listener a solid element of reference during the song."

(Carlisle, 102)

"Motive two, one of even greater importance, is a three-note melodic and rhythmical motive heard at each statement of the words, 'Where she dwells.'"

(Carlisle, 102)

"Example 12. 'Ditty,' measures 14-15." (Carlisle, 103) |

"It also returns every time in exactly the same structure, signaling the end of each musical section. While the poem inherently creates the means for this musical repetition, Finzi does provide a small, structural change in the motive at the conclusion of sections two and four that adds some variety. The motive in sections one, three, and five concludes with the music underlying the word 'dwells,' bringing each section to a logical resolution before continuing. however, at the end of sections two and four the return of this second motive occurs without a measure of resolution. Motive two becomes the 'resolution' in these two instances, thus causing both an overlapping of sections as well as a brief contraction of the concluding section. While this may seem a small point, it is nevertheless one of Finzi's subtle but important ways of adding diversity to a song to give it more interest."

(Carlisle, 103)

"The structure of the vocal melody is of less significance than the previously mentioned factors of meter and motives, but it does present a framework of greater melodic conjunction and smaller range than is often found in Finzi's other songs. This would normally be of little importance, but with a moving tempo, complex poetry, and Finzi's propensity for a one not per syllable structure, this factor assumes greater significance. This poem creates numerous difficulties for musical setting, due in no small part to the actual number of words in each stanza. Finzi's more common approach to vocal melodies, which often incorporated a greater vocal range and more disjunct, arpeggiated motion, would have caused the vocal line to be terribly unwieldy. However, his decision to emphasize conjunct movement softens the aspect of excessive declamation, and permits a smoother, more natural melodic architecture throughout the song than would otherwise be possible."

(Carlisle, 103-4)

"The tempo, harmony, and texture require little discussion, as there are few significant changes in these areas. The tempo changes only for expressive rubato at sectional endings, but its textural consistency provides an appealing musical 'drive' and energy throughout the piece. The texture is somewhat light by Finzi's standards, with a substantial emphasis on chords of three notes. There are exceptions of course, such as measures 17-18 and 38-39, in which full homophonic chords containing five notes each are heard, but these are few. There is an extensive use of passing tones, as is true in most of Finzi's songs, that creates the sensation of much textural flexibility, but in general the overall textural weight is light."

(Carlisle, 104)

"Both the constancy of a moving tempo and the general lightness of texture are in keeping with the basic mood and character of this poem, which is more extroverted than some found in this cycle. The only moment in the song that even approaches introspection occurs in measure 42 at the word 'smart.' Finzi uses the sharp dissonance of a minor second in the third beat of the measure to express the 'smart severe,' or deeply felt pain, of the poet at his thought of how it would feel to have never met or known his beloved. This is the only significant moment of harmonic interest at any point during the song, but for that reason this lone chord stands out more keenly than it would in a more chromatic setting. Finzi has chosen to eschew the complexity brought about by more extensive harmonic and temporal changes, instead preferring to concentrate on metrical elements conducive to good declamation and a strong sense of melodic lyricism. The directness of this approach creates in this case a wonderfully expressive and uncomplicated musical portrait that in its entirety is very appealing."

(Carlisle, 104-5)

Comments about Performance

"This song presents few musical problems for the performer outside of proper and expressive text declamation. The very character and nature of the piece requires an honest, direct approach to its interpretation'; anything more would create an overly affected performance. The only tempo marking is that of [quarter note] - c. 100 (Con moto) at the beginning, although the expressive marking of semplice is also indicated. Other expressive markings throughout the piece are those of ritardando that highlight natural moments for slight rubato, and a poco tenuto in measure 45. These are all quite appropriate and would present no difficulties for reasonably sensitive performers. Most of the dynamic markings in either accompaniment or vocal line are adequate for the needs of this piece; no extensive dynamic contrast is required or necessary. However, performers should take special care to observe the piano from measure 29 to 31; this is a poetic aside, and should be treated in a slightly different fashion than the rest of the text."

(Carlisle, 105-6)

"Breath marks for the singer, on the other hand, do not seem particularly appropriate in this song. For instance, a full breath does not seem necessary after the word "be" in measure 29; an expressive lift would be much more appropriate, allowing both singer and accompanist a longer and more musical sense of phrasing. The same could be said of the breath mark for the singer in measure 53 Finally, while the breath mark in measure 33 after the word "is" indicates a truly important moment requiring a textual break, a lift at this point followed by a full breath after the word "change" in measure 34 would be more appropriate. The increased length of the vocal phrase would not in most cases cause a performer undue difficulties, and it would allow a smoother, more natural breath than the one indicated."

(Carlisle, 106)

"The technical demands of this piece are not extensive; it has a very short range, little more than an octave, and the tessitura should be quite comfortable for most young tenors. There is certainly a need for a good sense of rhythm, but the overall character of the song is not complex, and its emphasis on a moving lyricism would most likely be quite attractive to a young singer. The most difficult aspects of this piece are the complexity of the poetry, and how to declaim the text in as natural and unaffected a manner as is possible given Finzi's style of text setting. Neither of these is insurmountable for a young tenor if he has the patience and guidance necessary to fully understand the poem. Most graduate-level tenors should be able to handle this piece with little difficulty, and while it is somewhat more problematic for an undergraduate, given adequate literary study, its relative technical and musical ease would make it even at the level an excellent recital selection."

(Carlisle, 106-7)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Ditty by Leslie Alan Denning. Dr. Denning extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated May 1995, is entitled:

A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page fifty-three and concludes on page fifty-six of the dissertation.

"Hardy's "Ditty" appeared in his collection called Wessex Poems containing fifty-two titles. Of these only four had been previously published, though the works were written over the span of many years. It seems Hardy never anticipated that the poems might be published, yet in 1898 the poems were presented complete with illustrations by the poet as well as personal footnotes describing places and people depicted. This particular poem was dedicated to Hardy's first wife, Emma Lavinia Gifford. Within these verses our young idealist experiences young innocent love. His description includes the remembrance of his beloved, the change she has brought to his life, and the good fortune that brought their two hearts together."

(Denning, 53)

"The craftsmanship present in this second song of the set is quite a contrast to that in the first. "Ditty" is obviously inspired by melodic folk songs which are especially English in style, reminiscent of common hymn tunes. Here Finzi has treated a simple love poem in the conventional style of a sentimental ballad, but the song escapes triteness through the composer's extreme regard for subtle mood changes and poetic meter. At the outset, the song may even appear artless. The form could easily be regarded as straightforward strophic composition; however, while each stanza has phrases that appear in the other, there is no direct strophic repetition present. Finzi has disguised the simplicity of his vocal lines by employing irregular phrase lengths and elasticizing rhythms in response to the patterns of the text. Though it may appear simple the structure of the melody holds together securely and could well stand without the support of the accompaniment."

(Denning, 54)

"In the key of G-major, "Ditty" possesses a simple melodic diatonicism inherited from the long line of eighteenth-century English composers who preceded Finzi. The accompaniment here is very supportive of the vocal line, often doubling it chordally. While less complete than the Bach-like counterpoint of 'A Young Man's Exhortation,' the interludes prove interesting in their resemblance to mini-fugues. In the beginning of the second and fourth stanzas are several things worthy of note. Both stanzas begin with a brief semi-fugal movement in the accompaniment which resolves into simple chords to point up the text. The melody which is shared at the beginning of these two stanzas also pays tribute to Vaughan-Williams whom Finzi respected greatly. It is borrowed from Vaughan-Williams' 'Linden Lea.'"

(Denning, 54-5)

"Example 4: Ditty, Measures 15-17." (Denning, 55) |

"Example 5: Ditty, Measures 36-38." (Denning, 55) |

"In 'Ditty' the accompaniment reveals a series of seventh chords and suspensions which work effectively within the simple harmonic language present here. As the song ends, Finzi contrasts the acceptance of fate present in Hardy's poems with an underlying feeling of hope for the future as the melody peaks in measures fifty-four and fifty-five. As the accompaniment triumphantly recounts material from the first stanza it eventually resolves to a subtle last statement of the text "where she dwells" and the accompaniment rambles off through a series of suspensions and passing tones to rest on a tonic chord."

(Denning, 55)

"'Ditty' is somewhat of a gem in that it is at the same time simple, yet effective and moving. This is a perfect example of Finzi's ability to triumph within the boundaries of his chosen musical language. Here Finzi has adequately provided performance indication for dynamics and mood changes. Perhaps the singer's greatest challenge is to negotiate breath and phrasing of the often on-running vocal line."

(Denning, 56)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Ditty by Carl Stanton Rogers. Permission to post this excerpt was extended by Dr. Rogers' widow, Mrs. Carl Rogers on March 1st, 2011. Dr. Rogers' thesis dated August 1960, is entitled:

A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page twenty-one and concludes on page twenty-eight of the thesis. (Rogers, 21-28)

Part I, Number 2

"Ditty"

The form of this song may be called A B C B¹ C¹. It has the rather distinct feeling of a strophic song, since many of the same melodic leaps are used in corresponding places in each stanza.

The setting of the text is entirely syllabic. The song is in the style of a folk song, has a definite lyric quality, and is quiet and meditative.

A point of definite interest is the scale used by the composer in this song. The key signature contains one sharp, and the first stanza seems much of the time to be in the key of G-major. However, the music of the first stanza does not contain the leading tone, or F-sharp, in the vocal line. As to the presence of F-sharp in the vocal line of the entire song, the table below affords a clearer view of its use in this instance. Table II shows the relative total duration of each of the scale tones in the melodic line of the entire song. The infrequent use of the seventh scale degree is particularly noticeable.

EMPHASIS ON SCALE DEGREES OF "DITTY" BY DURATION

Scale Degree |

Number

of Beats |

|

1 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

49 1/2 |

6 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

39 1/2 |

5 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

31 1/4 |

2 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

30 1/3 |

3 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

29 5/12 |

4 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

18 1/3 |

7 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

6 1/3 |

*[quarter note] = unit of the beat |

There is a constant fluctuation in the feeling of the tonality between that of G-major and E-minor due in part to the fact that the sixth scale degree, or E-natural, is of longer total duration than the dominant note, D-natural.

It is also pertinent to note that at the cadences the leading tone is avoided except as a nonharmonic tone introduced after the tonic chord has sounded. Measures fourteen and fifteen as shown in Figure 7, demonstrate this point.

Fig. 7 -- "Ditty," measures 14 and 15, absence of leading tone at the cadence.

Another explanation that may be adduced to account for the vagueness of tonality in the melody is that the scale is a primitive one, related to the pentatonic melodies of English folksong. Cecil Sharp's investigations in this area serve as an invaluable guide in the discussion and classification of these scales.

Very nearly all these Appalachian tunes [English folk tunes collected by Sharp in the Southern Appalachian Mountains of North America] are cast in "gapped" scales; that is to say, scales containing only five, or sometimes six, notes to the octave, instead of the seven with which we are familiar, a "hiatus" or "gap" occurring where a note is omitted.

(Sharp, xxx-xxxi as quoted by: Rogers, 23)

Sharp goes on to state his belief that these early pentatonic scales were the first forms of scales evolved by primitive folk singers which were in any way comparable with our modern major or minor scale.

Originally, as may be gathered from the music of primitive tribes, the singer was content to chant his song in monotone, varied by occasional excursions to the sounds immediately above or below his single tone, or by a leap to the fourth below. Eventually, however, he succeeded in converting the whole octave, but even so, he was satisfied with fewer intermediate sounds than the seven which comprise the modern diatonic scale. Indeed, there are many nations at the present day which have not yet advanced beyond the two-gapped or pentatonic scale, such as , for instance, the Gaels of Highland Scotland; and, when we realize the almost infinite melodic possibilities of the five-note scale, as exemplified in Celtic folk music and, for that matter, in the tunes printed in this volume, we can readily understand that singers felt no urgent necessity to increase the number of notes in the octave. A further development in this direction was, however, eventually achieved by the folk-singer; though for a long while, as was but natural, the two medial notes required to complete the scale were introduced speculatively and with hesitation. . . The one-gapped or hexatonic scale, and the seven-note or heptatonic scale are, as we have already seen, derivatives of the original pentatonic obtained by the filling, respectively, of one or both of the gaps.

(Sharp, xxxi-xxxiii as quoted by: Rogers, 24)

Sharp classifies all of these early English folk songs according to one of five original pentatonic modes. The five pentatonic modes were derived in the following way:

If from the white-note scale of the pianoforte the two notes E and B be eliminated, we have the pentatonic scale with its two gaps in every octave, between D and F and between A and C. As in each one of the five notes of the system may in turn be chosen as tonic, five modes emerge, based, respectively, upon the notes C, D, F, G, and A. The gaps, of course, occur at different intervals in each scale, and it is this distinguishing feature which gives to each mode its individuality and peculiar characteristic.

(Sharp, xxxi, xxxiii as quoted by: Rogers 24-5)

Mode I and the scales derived from it are shown in Figure 8.

(Sharp, xxxii as quoted by: Rogers, 25)

Fig. 8 -- Mode I (Pentatonic) and its derivative scales.

Clearly, the derivative six-note scale of Mode I signified as "Hexatonic a." by Sharp applies to the scale of "Ditty," the song presently under consideration. The fact that the leading tone is avoided to such a great degree, added to the observation that its total duration is so small, point to the influence of the folk-scale previously discussed.

Turning to a consideration of the meter of "Ditty," it can be seen that the song contains no meter signature. The meters employed, however, alternate between 3/4, 4/4, 5/4 and 6/4. The sometimes rather frequent meter changes are used to enhance the accents and pauses in the text. Three such changes are shown in Figure 9. The meters employed are 6/4, 3/4, and 4/4.

Fig. 9 -- "Ditty," measures 16, 17, 18, 19, frequent changes of meter.

The harmonic structure of "Ditty" is completely tertian. The nature of the cadences has already been noted (Figure 7 -- measures fourteen and fifteen). A complete analysis of the root movement of the chords for the entire song is given in Table III.

TABLE III

AN ANALYSIS OF THE FUNDAMENTAL ROOT MOVEMENT

OF "DITTY"

Interval |

Number of Occurrences

|

|

Second |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

84 |

Fourth |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

45 |

Prime |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

38 |

Fifth |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

30 |

Third |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

20 |

Sixth |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

11 |

Tritone |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

2 |

Based on Table III, it can be seen that 36 percent of all root movement in the song is by the interval of the second, indicating a mode of composition similar to that of the first song in this cycle, "A Young Man's Exhortation." (See Table I, An Analysis of the Fundamental Root Movement, Section D of "A Young Man's Exhortation.")

A harsh dissonance between the vocal line and the piano accompaniment is used by the composer in this song, as shown in Figure 10.

Fig. 10 -- "Ditty," measure 42, dissonance between vocal line and piano accompaniment.

The tonal center at the point of dissonance is E-minor, and the dissonant note is actually the leading tone, which is present in both its raised and lowered forms simultaneously. In this instance, the dissonance occurs on the word "smart," a word denoting pain or hurt. That this particular dissonance would be effective in performance is shown by the fact that the dissonance is well-prepared and left in the piano accompaniment, especially the note in its chromatically altered form (D-sharp).

The preceding was an analysis of Ditty by Carl Stanton Rogers. Permission to post this excerpt was extended by Dr. Rogers' widow, Mrs. Carl Rogers on March 1st, 2011. Dr. Rogers' thesis dated August 1960, is entitled:

A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas HardyThis excerpt began on page twenty-one and concluded on page twenty-eight of the thesis.

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of Ditty by Michael R. Bray. Dr. Bray extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on March 19th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1975, is entitled:

An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

This excerpt begins on page eighteen and concludes on page twenty-three of the thesis.

(Bray, 18-23)

DITTY |

||

|---|---|---|

BENEATH a knap where flown |

||

|

||

Within walls of weathered stone, |

||

|

||

From the files of formal houses, |

||

By the bough the firstling browses, |

||

Lives a Sweet: no merchants meet, |

||

No man barters, no man sells |

||

|

||

Upon that fabric fair |

||

|

||

Seems written everywhere |

||

|

||

But to friends and nodding neighbours, |

||

Fellow-wights in lot and labours, |

||

Who descry the times as I, |

||

No such lucid legend tells |

||

|

||

Should I lapse to what I was |

||

|

||

(Such will not be, but because |

||

|

||

Let me feign it) – none would notice |

||

That where she I know by rote is |

||

Spread a strange and withering change, |

||

Like a drying of the wells |

||

|

||

To feel I might have kissed – |

||

|

||

Otherwhere, nor Mine have missed |

||

|

||

Had I never wandered near her, |

||

Is a smart severe – severer |

||

In the thought that she is nought |

||

Even as I, beyond the dells |

||

|

||

And Devotion droops her glance |

||

|

||

What bond-servants of Chance |

||

|

||

I but found her in that going |

||

On my errant path unknowing, |

||

I did not out-skirt the spot |

||

That no spot on earth excels, |

||

|

||

"Ditty" is inscribed with the initials of Lavina Gifford, whom Hardy met in March of 1870 while still in London, and fell in love with her. (Bailey, 59) He described his state of mind during the following months: "He seems to have passed the days in town desultorily and dreamily-mostly visiting museums and picture galleries, and it is not clear what he was waiting for there. In his leisure he seems to have written the 'Ditty' in Wessex Poems." (Hardy, 101)

The opening verse depicts the rural isolation of St. Juliot, its tiny church, and its rectory with "walls of weathered stone: where Miss Gifford lived. Hardy was attracted to her by her painting, her music, and most of all her vitality. "She was so living," (Weber, 16) he used to say. Her impact upon his former life (He was susceptible to change after the great storm broke) is evidenced in his poem:

Should I lapse to what I was |

|

(Such will not be, but because |

|

Let me feign it) – none would notice |

That where she I know by rote is |

Spread a strange and withering change, |

Like a drying of the wells |

|

It is also characteristic of Hardy in meditating the slender chance that led him to her door: "What bond-servants of Chance / We are all." (Bailey, 60) Soon after, they married.

"Ditty" has a very distinctive simple country air about it and the beauty of Finzi's setting of this poem lies in his simplified melodies and accompaniment. He achieved this effect in several ways.

The harmonies in this song are traditionally set within the guidelines of theoretic progressions. A characteristic "walking" bass line has great effect upon the simplicity of the accompaniment and upon the harmonic structure. The functional harmony is often reduced to chords and a melody line as seen in the following example:

EXAMPLE 4: "Ditty" measures 32-33.

This also insures the clarity with which word-packed phrases are performed. The song contains no harsh chords and stays within the key of G Major. Finzi employs the six-chord very effectively throughout the song. It is generally employed either on stressed words (in two instances on high climax notes) or where the motion of the phrase needs to be impeded through the effect of a deceptive cadence to give added emphasis. Such is the case in the following passage:

EXAMPLE 5: "Ditty" measures 37-38.