Gerald Finzi

- Education

- Compositional Characteristics

- Works

- Unpublished Dissertation Excerpt

- Chia-wei Lee - A Performance Study of Gerald Finzi's Song Cycle "Before and After Summer

- The Solo Vocal Collections of Gerald R. Finzi Suitable for Performance by the High Male Voice by Samuel Rudolph Germany

- Two Gentlemen from Wessex: The relationship of Thomas Hardy’s poetry to Gerald Finzi’s music by John Keston

- Curtis Alan Scheib - Gerald Finzi's Songs for Baritone on Texts by Thomas Hardy

The information on this page is a biographical sketch for Gerald Finzi; offering the reader a basic knowledge of his life and work. There are some suggestions at the bottom of this page for resources and links that should help those looking for additional information.

“There could hardly be a more determinedly English musician in his work, his musical outlook, his tastes and recreations, his way of life, than Finzi. And what is remarkable is how self-made that life was.” (McVeagh, 67) |

Gerald Finzi, was a man drawn in several directions during his life. He was a man who devoured the written word. He was a man who realized life is short and that we should strive to leave something that makes a difference to humanity. He was a man acquainted with grief and war and despised choices that some men make for others. He was a man who fought for the underdog. He was a man who liked to take walks in his youth so as to soak up nature and to become grounded to his native England. Lastly, he was a man who believed in conservation of music and of the simple things in life, namely apple trees. One can find all of these attributes in the literature he read as well as the songs he composed.

Gerald Finzi: Was born in London on July 14, 1901 and died on September 27, 1956 in the hospital at Oxford, England.

Father: John Abraham (Jack) Finzi (1860-1909)

His occupation was that of a ship broker. He died rather horrifically with cancer of the mouth when Gerald was eight years old.

Mother: Eliza (Lizzie) Emma [née Leverson] Finzi (1865-1955)

She was a home maker and amateur pianist.

Siblings:

- Kate (Finzi) Gilmour (Feb. 28, 1890-)

Author of: Eighteen Months in the War Zone: The Record of a Woman's Work on the Western Front - published by Cassell and Company in 1916.

- Felix John (Aug. 11, 1893 - Aug. 3, 1913)

- Douglas Louis (Feb. 17, 1897 - July 7, 1912)

- Edgar (Dec. 17, 1898 - Sept. 5, 1918)

Spouse: Joyce (Joy) Black (March 3, 1907 - June 14, 1991)

She married Gerald on September 16, 1933. Her occupation was that of an artist and a home maker.

Children:

- Christopher (Kiffer), born: July 1934

Continued Gerald Finzi's leadership of the Newbury String Players after Gerald's death. - Nigel, born: August 9, 1936 and died June 25, 2010 Obituary for Nigel Finzi

From almost the outset of his existence Gerald Finzi seemed to want to control his own education. He resisted a formal education by feigning sickness and consequently was taught privately. What he did not learn from private tutors he learned on his own primarily from reading. He studied music formally, first with Ernest Farrar (1885-1918) between the years 1915 and 1916. Farrar had been a student of Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) and was also friends with Ralph Vaughan Williams. At the onset of the First World War, Farrar joined the army and made arrangements for Finzi to study with Sir Edward Bairstow (1874-1946). Bairstow was the organist and choirmaster at York Minster. Finzi studied with Bairstow between 1917 and 1922. In 1918 Finzi was given the news that his first teacher Ernest Farrar had been killed in action. This came as quite a shock to the young Finzi who before he was eighteen had lost his father, and all three of his brothers as well as Farrar who had become a father figure to him. In 1922 Finzi stopped studying with Bairstow and moved with his mother to Painswick in Gloucestershire. Finzi was attempting to find his own voice by creating a utopia of peace and solitude in the countryside. In 1925 Finzi moved back to London and began studying counterpoint with Reginald Owen Morris (1886-1948). The move to London had several benefits for Finzi. First and foremost it allowed him to establish a network of friends that would serve him the remainder of his life. Many of these friends became good colleagues that then gave Finzi advice as well as constructive criticism. The list of friends and colleagues included: Howard Ferguson, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Arthur Bliss, Robin Milford, Edmund Rubbra, and Gustav Holst.

(McVeagh)

Influences on Finzi's Musical Composition:

They include composers that he studied while learning music composition with Ernest Farrar, Sir Edward Bairstow, and R. O. Morris. They surely included all of the great early composers but Finzi also appreciated lesser known composers as well as his own contemporaries. Diana McVeagh writing a Finzi biography for Grove Music Online lists the following composers that contributed to Finzi's developing style of composition:

Melodically and harmonically Finzi owed something to Elgar and Vaughan Williams; as well as occasional flashes of Bliss and Walton, Finzi’s love and knowledge of Parry can be discerned. To none of these composers was he in debt for the finesse of his response to the English language and imagery, or for his vision of a world unsullied by sophistication or nostalgia. (McVeagh, Grove Music Online) |

Ralph Vaughan Williams stands out in the list above as one who possibly helped Finzi the most in his musical development as well as success as a composer. Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) was extremely helpful to Finzi on various fronts. Finzi admired Vaughan Williams compositions and when Finzi was allowed in to the inner circle of Vaughan Williams' friends he gained numerous contacts and avenues for further advancement. Vaughan Williams' music was attractive to Finzi because it offered a less complicated harmonic palate and also its use of English folk song for its foundation was of an interest to Finzi. Vaughan Williams was also an extremely positive influence for Finzi in that he encouraged Finzi on numerous occasions and he, Vaughan Williams, also seems to have exerted a calming influence into Finzi's life.

A person that Diana McVeagh doesn't mention as to someone who deeply influenced Finzi's composition was that of composer and pianist, Howard Ferguson (1908-1999). Ferguson must be given credit for helping Finzi on several fronts. They both had met while studying with R. O. Morris and became life long friends. Finzi was not a good pianist and so many times Ferguson would be the one that not only played through Finzi's compositions for the first time but would also make suggestion as to how to improve the composition. His suggestions advised Finzi on such things as the the piano accompaniment, interpretive marks such as dynamics and phrasing as well as a general sounding board for ideas. Ferguson also played the premiere performances of many of Finzi's works that involved the piano.

Another influence on Finzi's composition would also include his study and consequent preservation of lesser known and sometimes forgotten composers. His study of their works enhanced his own style in the same way young composers had done since the time of J. S. Bach. Through his preservation efforts of forgotten composers he was either directly or indirectly influenced. The composers works that Finzi sought to preserve include those of: Ivor Gurney (1890-1937), William Boyce (1711-1779), and Sir Hubert Parry (1848-1918) who was mentioned by Diana McVeagh in her biographical remarks for Gerald Finzi.

Compositional Characteristics:

One of the characteristics that comes to mind immediately with regards to Finzi's song writing is his ability to set the words. They seem quite naturally declaimed in his songs. Stephen Banfield comments on Finzi's ability to set words carefully: "The purity of Finzi's word-setting has often been remarked upon. In addition to shaping his melodic contours to the rise and fall of the conversing or the reciting voice, he is thorough, probably unconsciously." (Banfield, 282) Diana McVeagh concurs with Banfield's remarks but goes further to say that Finzi's style directly correlates to his inspiration from the texts themselves: "Finzi unerringly found the live centre of his vocal texts, fusing vital declamation with a lyrical impulse in supple, poised lines." (McVeagh, Grove Music Online) This craftsmanship with words probably comes from his early love of the printed word and how it was his teacher as well as friend for many years while growing up. When Finzi died in 1956 his literary library was larger than that of his musical library. His good word setting could also possibly stem from his working on and off on a song sometimes for many years. While discussing Finzi's compositional style Mark Carlisle had the following to say in his dissertation: "He [Finzi] was a slow and fastidious composer, often writing many sketches of music for different pieces that would be put a way for several years before being revived and completed."

(Carlisle, 8-9)

Another characteristic of Finzi's song writing is his use of syllabic writing, meaning that he almost never set more than one syllable per note. Finzi seems to strive for the purity of the word and not to adorn it with a melissma. Diana McVeagh concludes the lack of melissma in Finzi's writing was because he did not attempt to paint the text as his contemporaries and those long before him had: "He was little concerned with word-painting, and his songs are virtually syllabic (in contrast with Britten’s and Tippett’s)." (McVeagh, Grove Music Online)

Still another characteristic of Finzi's writing is his harmonic support and how he seemed to steer clear of practices that were going on with his contemporaries. Diana McVeagh says: "Finzi's sense of tonality and form was idiosyncratic." (McVeagh, Grove Music Online) Mark Carlisle also addresses Finzi's harmonic palate in his dissertation:

"His [Finzi's]harmonic language incorporated a tension range that was considerably lower than that of many of his contemporaries. He refused to use the greater level of dissonances available to him at the time, but instead concentrated on developing the most significant musical strength possible within the harmonic spectrum . . . Most of his songs used major and minor key structures, though frequently he also used amodality as a harmonic framework; only occasionally did he venture to use some of the more complex, sophisticated harmonies found in the works of his peers. Functional relationships within a given key were at times unusual and unorthodox, but rarely excessively complicated." (Carlisle, 10-11) |

Finzi's characteristics are conservative especially by contemporary music standards. Finzi did not attempt to move music forward with his counter point or harmonic palate but instead thought it more important to allow the poetry to speak for itself. Stephen Banfield writes in his Finzi biography:

"Finzi's work is certainly conservative, but it is not to be dismissed with most of what falls under that label. Conservatism itself is no fault. The trouble is that in the arts it often accompanies, or is a manifestation of, an inferior sensibility. . . His music had always shown in spite of its relatively conventional language, a distinction of personality and thought, a fastidiousness of expression, and a fineness of taste that rejected all the banalities - lyrical, rhetorical, or jovial - characteristic of most conservative music, even by composers of real talent." (Banfield, 472) |

Donald Eugene Vogel, in his dissertation dating from ten years after Finzi's death believes Finzi's music is a bit of a hodgepodge of styles ranging from the seventeenth century through the twentieth century but he also believes it is held together by Finzi's musical convictions:

"Gerald Finzi's style of composition . . . emerges as one that is conservative, and one that is strongly influenced by characteristics most typical of the Romantic period of music. A cleanliness of texture lines, economical use of material, and long contrapuntally conceived melodies, which make little use of chromaticism, indicate his intense study of the music of seventeenth and eighteenth century composers. Twentieth century characteristics seen in the compositions are frequent unorthodox key and chord relationships, and tonalities that are often mixed or polychordal in their construction. Two traditional sources for English compositional style (folk music and church music) reflect a strong influence in the songs of Finzi. The composer's primary compositional consideration appears to have been to illustrate the textual thought being conveyed in the poem, rather than concerning himself with the means of expression." (Vogel, abstract) "Gerald Finzi was a slow, methodical, craftsman-like composer with a rare gift of musical integrity that would not allow him to force a piece of music into compositional form. He would not deliberately manipulate a thematic idea or a harmonic passage in order to make it fit into a song. He detested the use of contrived formulas and stylish patterns used for the sake of making a composition different; therefore, his music is void of musical gimicks." |

Finzi's contribution to vocal literature is one that seeks to elevate English poetry. He was not intimidated by the poetry of Thomas Hardy and instead embraced it even though many thought it was not possible. His music is a fabric woven from the past and the present tinged with a folk idiom at times. He laboured for his fruit and was not appreciated greatly for his craftsmanship during his life but his work did not go in vain for his songs continue to grow in popularity, a testament to his fine work.

Occupation:

Finzi fortunately did not have to support himself financially from his work but instead relied on funds that came from his inheritance and frugality. Later when he married Joyce Black he also had the support of her family for finances. His occupation was that of a composer. Before getting married Finzi briefly taught composition at the Royal Academy of Music from 1930 to 1933. During World War II, Finzi was drafted into the Ministry of War Transport (1941-5) and was given some compensation for his service. Also, during the war Finzi founded the Newbury String Players. This group was started to primarily help with morale in the country but it also gave Finzi a vehicle for his music and the music of lesser known composers. His work with the Newbury String Players was not for financial reasons but rather for his own personal edification and community involvement. Finzi also did some tutoring of private students while living at his home of Ashmansworth. Not an occupation but rather a hobby that consumed Finzi, and one that he was extremely proud of, included his conservation of threatened apple tree species. This hobby was again not for financial gain but just another example of Finzi's drive to preserve and protect.

Voice and piano: By Footpath and Stile, A Young Man's Exhortation, Earth and Air and Rain, and Let Us Garlands Bring.

Posthumously published works for voice and piano: Till Earth Outwears, Oh Fair To See, I Said To Love, and To A Poet. After Finzi's death, Howard Ferguson helped Joy and Christopher Finzi assimilate the songs listed above and get them ready for publication. Finzi's Tall Nettles was arranged for voice and piano by Christian Alexander.

Solo voice and orchestra: By Footpath and Stile, Dies Natalis, Farewell to Arms, Two Milton Sonnets, Let Us Garlands Bring, Four Songs from Love's Labour's Lost, When I set out for Lyonnesse, Published posthumously: In Years Defaced (six Finzi songs for tenor voice arranged by Colin Matthews, Jeremy Dale Roberts, Christian Alexander, Judith Weir, and Anthony Payne.

Chorus and orchestra: Lo, The Full, Final Sacrifice, God is gone up, Intimations of Immortality, For St. Cecilia, Let us now praise famous men, Magnificat, In terra pax, Muses and Graces, and Requiem da camera.

Orchestral works: A Severn Rhapsody, New Year Music (Nocturne), Love's Labour's Lost, The Fall of the Leaf - Elegy for Orchestra, Introit, Eclogue, Clarinet Concerto, Grand Fantasia and Toccata, Cello Concerto, and Violin Concerto.

String orchestra: Romance and Prelude.

Chamber music: Introit, Interlude, Elegy, Five Bagatelles, Prelude and Fugue.

Chorus and piano or organ: Ten Children's Songs (songs to poems by Christina Rossetti), Three Anthems, Lo, the full, final sacrifice, Let us now praise famous men, Magnificat, Muses and graces, and Two Motets.

Unaccompanied chorus: Three Short Elegies, Seven Unaccompanied Part Songs, Thou dids't delight mine eyes, All this night, and White-flowering days.

Work best known for: Let Us Garlands Bring

List of Songs |

||

Song |

Song Set or Work |

Poet |

Amabel |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

Aria 'His golden locks' |

Farewell to Arms |

George Peele |

As I lay in the early sun |

Oh fair to see |

Edward Shanks |

At a lunar eclipse |

Till Earth outwears |

Thomas Hardy |

At Middle-Field Gate in February |

I said to love |

Thomas Hardy |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

Thomas Hardy |

Before and after summer |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

The Birthnight |

To a poet |

Walter de la Mare |

Budmouth Dears |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

Thomas Hardy |

Channel firing |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

Childhood among the ferns |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

Clock of the Years, The |

Earth and Air and Rain |

Thomas Hardy |

Come away, death |

Let us garlands bring |

William Shakespeare |

Comet at Yell'ham, The |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

Thomas Hardy |

Dance continued, The |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

Thomas Hardy |

Ditty |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

Thomas Hardy |

Epeisodia |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

Exeunt Omnes |

By footpath and stile |

Thomas Hardy |

False Concolinel |

Love's Labours Lost/Songs for Moth |

anon. |

Fear no more |

Let us garlands bring |

William Shakespeare |

For life I had never cared greatly |

I said to love |

Thomas Hardy |

Former Beauties |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

Thomas Hardy |

Harvest |

O fair to see |

Edmund Blunden |

He abjures love |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

Her temple |

A Young Man's Exhortation |

Thomas Hardy |

How soon hath time |

Two sonnets by John Milton |

John Milton |

I look into my glass |

Till Earth outwears |

Thomas Hardy |

I need not go |

I said to love |

Thomas Hardy |

I said to love |

I said to love |

Thomas Hardy |

I say 'I'll seek her side' |

Oh fair to see |

Thomas Hardy |

In a churchyard |

Earth and Air and Rain |

Thomas Hardy |

In five-score summers |

I said to love |

Thomas Hardy |

In the mind's eye |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

Intrada |

To a poet |

Thomas Traherne |

Introduction 'The Helmet now' |

Farewell to Arms |

Ralph Knevet |

In years defaced |

Till Earth outwears |

Thomas Hardy |

It never looks like summer |

Till Earth outwears |

Thomas Hardy |

It was a lover and his lass |

Let us garlands bring |

William Shakespeare |

June on Castle Hill |

To a poet |

F. L. Lucas |

Let me enjoy the earth |

Till Earth outwears |

Thomas Hardy |

Life laughs onward |

Till Earth outwears |

Thomas Hardy |

Market-Girl, The |

Till Earth outwears |

Thomas Hardy |

Master and the leaves, The |

By footpath and stile |

Thomas Hardy |

O mistress mine |

Let us garlands bring |

William Shakespeare |

Ode: on the rejection of St. Cecilia |

To a poet |

George Barker |

Oh fair to see |

Oh fair to see |

Christina Rossetti |

Only the wanderer |

Oh fair to see |

Ivor Gurney |

On parent knees |

To a poet |

William Jones |

Overlooking the river |

Before and after summer |

Thomas Hardy |

Oxen, The |

By footpath and stile |

Thomas Hardy |

Paying Calls |

By footpath and stile |

Thomas Hardy |

| Phantom, The | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| Proud songsters | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| Rapture, The | Dies Natalis | Thomas Traherne |

| Rhapsody, The | Dies Natalis | Thomas Traherne |

| Riddle Song, The | Love's Labours Lost | William Shakespeare |

| Rollicum-Rorum | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| Salutation, The | Dies Natalis | Thomas Traherne |

| Self-unseeing, The | Before and after summer | Thomas Hardy |

| Shortening Days | A Young Man's Exhortation | Thomas Hardy |

| Sigh, The | A Young Man's Exhortation | Thomas Hardy |

| Since we loved | O fair to see | Robert Bridges |

| So I have fared | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| Songs of Hiems and Ver | Love's Labours Lost | William Shakespeare |

| Song for Moth | Love's Labours Lost | William Shakespeare |

| Summer schemes | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| To a poet | To a poet | James Elroy Flecker |

| To Joy | O fair to see | Edmund Blunden |

| To Lizbie Brown | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| Too short time | Before and after summer | Thomas Hardy |

| Transformations | A Young Man's Exhortation | Thomas Hardy |

| Two lips | I said to love | Thomas Hardy |

| Voices from things growing in a churchyard | By footpath and stile | Thomas Hardy |

| Waiting Both | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| When I consider | Two Sonnets by John Milton | John Milton |

| When I set out for Lyonnesse | Earth and Air and Rain | Thomas Hardy |

| Where the picnic was | Before and after summer | Thomas Hardy |

| Who is Silvia? | Let us garlands bring | William Shakespeare |

| Wonder | Dies Natalis | Thomas Traherne |

Publishers:

- Boosey and Hawkes

- Banks Music for: (Requiem da camera)

Religious and Political beliefs:

- Gerald Finzi's ancestors were Jewish but he considered himself agnostic. Nevertheless he wrote several choral works suitable for religious services.

- His political beliefs included remaining active in the political process and with regards to conflict, he considered himself a pacifist.

The following are biographical comments by Chia-wei Lee regarding the life of Gerald Finzi. Dr. Lee extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on February 16, 2012. His dissertation dated 2003, is entitled:

A Performance Study of Gerald Finzi's Song Cycle

"Before and After Summer"

This excerpt begins on page 1 and concludes on page 27.

The preceding were biographical comments by Chia-wei Lee regarding the life of Gerald Finzi. Dr. Lee extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on February 16th, 2012. His dissertation dated 2003, is entitled:

A Performance Study of Gerald Finzi's Song Cycle

"Before and After Summer"

The excerpt began on page 1 and concluded pn page 27.

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an excerpt from Samuel Rudolph Germany's dissertation. Dr. Germany extended permission to post this excerpt on December 20th, 2010. His dissertation dated August 1993, is entitled:

The Solo Vocal Collections of Gerald R. Finzi Suitable for Performance by the High Male Voice

The excerpts come from pages three through fifty-four, one hundred twenty-three through one hundred twenty-nine, one hundred thirty-one through one hundred thirty-five, and one hundred thirty-seven through one hundred thirty-nine.

Please choose a tab below to navigate to the section indicated.

Pertinent Biographical Data

Gerald Raphael Finzi was born on July 14, 1901, into a prosperous businessman's family. This heritage allowed Finzi a comfortable provision, for which he was grateful the rest of his life, but it offered little of the emotional support which he direly needed. (J. Finzi) Among the five Finzi children, Gerald was the only one with musical talent, and was understood, in this respect, only by his mother. From the beginning, those who could have been his first companions and friends, his sister and brothers, treated him as a strange. (Caesar, vii) (J. Finzi) As a result, a sense of isolation developed in Finzi during his childhood and remained with him to some extent into his adult years. Finzi's sense of security, then, was sharply shadowed by the successive premature deaths of virtually all significant male figures of his young life. Thereafter, Finzi was frequently haunted by thoughts of transience and mortality. (Caesar, vii) (McVeagh) Thus affected with an introspective nature, Finzi sought and found solace in literature. (McVeagh, 67)

His private world of "companion minds from other times" (J. Finzi) served, furthermore, to compensate for what his conventional education lacked. Finzi achieved dismissal from prep school by feigning swooning fits. A subsequent period of tutoring was brought to a premature close by the outbreak of World War I. Then after the age of thirteen, he was largely self-educated, believing he could determine what he needed and learn it for himself. The great minds of the past were available to him by his reading their works. (McVeagh, 67) The amount he read, especially during his teens and early manhood, was remarkable. His life's philosophy and his well-spring of song emanated from this devotion to literature. (J. Finzi)

By his early teens Finzi conceived the desire which was to regulate all his future activity: he would be a composer. Music became a primary focus, in spite of the obstacles before him. Sir Charles Stanford of the Royal College of Music strongly discouraged him from a career in music due to Finzi's lack of facility on any instrument. (Ferguson) Virtually the only encouragement Finzi received came from his mother as he turned to pursue his study via private instruction. (Caesar)

His first major study of composition, and that which was of the most profound influence, was with Ernest Farrar from 1914 to 1916. Farrar was thoroughly Stanford-trained, acquainted with many important musicians, and himself an active composer. "He understood the sensitive, stubborn teenager, who, had he met at that early stage a dry, orthodox teacher, might easily have withered." (McVeagh, 67) It is understandable, therefore, that Farrar's calling up to war and subsequent death on the front made such an imprint upon Finzi's consciousness that he could still remember it with a great deal of bitterness and melancholy even thirty-five years later. (Caesar)

Finzi's remaining compositional study was with Sir Edward Bairstow until 1922. This contact gave Finzi crucial exposure to sacred choral music and observations of the lessons of other pupils, among them solo singers. It is almost certain that Finzi learned much of his skill in vocal composition this way, for he never studied singing himself. (McVeagh, 67) It was here that he first heard the young soprano, Elsie Suddaby, perform Ivor Gurney's "Sleep," composition which was to affect him immensely. (Ferguson) In 1922, Finzi moved to rural Painswick to compose in the romantic seclusion of the countryside of Elgar, Vaughan Williams, and Gurney. (McVeagh, 594)

A subsequent study of counterpoint with Richard O. Morris in 1925 led Finzi to move to London, Morris and others convinced Finzi that he needed a change of environment to stimulate his composition and to counteract his introspective bent. The London period, which extended from 1926 to 1933, was a fruitful time for Finzi. He frequented concerts, theaters, and galleries, becoming thoroughly acquainted with all the current trends in music and art. For the first time, he mingled with other young artists/musicians, developing a circle of friends including Howard Ferguson, Edmund Rubbra, Robin Milford, and Marion Scott. (McVeagh, 594) Finzi had first contacted Ralph Vaughan Williams via correspondence in 1923, and by 1927 he was a regular visitor in the renowned composer's home. Records of a steady stream of correspondence between the two show a great deal of mutual admiration and shared advice concerning composition. Through Vaughan Williams, Finzi also became friends with Gustav Holst. (Cobbe, 9)

Finzi's compositional efforts at that time produced some of his freshest, most individual, music as well as some weaker pieces. Occasional performances of his works increased his confidence as his name became known, In 1928, Vaughan Williams conducted the first performance of a violin concerto by Finzi, although it was later withdrawn from publication, along with the Severn Rhapsody. (McVeagh, 594) There were performances of individual songs on poetry by Thomas Hardy and the first of many Hardy collections (A Young Man's Exhortation in 1933). Among his other works of the time were a great number of unfinished song fragments and complete single songs, many of which later became parts of published sets for high male voice, such as Two Sonnets by John Milton, Farewell to Arms, and Dies Natalis. (Banfield, 444-5) Further acknowledgement came with Finzi's appointment to teach composition at the Royal Academy of Music (1930-3). (McVeagh, 594)

It was clear, however, that London provided too much stimulation for someone of Finzi's enormous intellectual and nervous energy. His marriage to Joyce Black (also called Joy) in 1933, though conducted in private simplicity with the Vaughan Williamses as sole witnesses, (Cobbe, 10) was seen by Finzi as saving him from a nervous breakdown. (Caesar, viii) Howard Ferguson recalls the intense, restlessness of his character prior to this:

Holst was a great friend, you know, and the first time after they were married, they went to visit him. Dear Gustav said to Joy, "Have you managed to get him to sit down while he's taking breakfast yet?" (Ferguson) |

Ferguson states that beneath a vibrant, buoyant exterior, Finzi allowed only a privileged few to see an underlying pessimism, which was even more intense at that point in his life. (Ferguson, 134) Reports indicate that Joy's liberating warmth, practical efficiency, and undying support of Gerald's work did much to ease his introspective solitude.

(McVeagh, 594) Joy, herself an artist of astounding natural gifts in sculpting and drawing, selflessly and untiringly gave of herself to free Gerald to do his work. Her immense strength of character proved to be one of his major resources for the rest of his life.

(Ferguson)

Soon after his marriage, it became clear to Finzi that quiet and concentration were absolutely essential to his compositional method. Earlier, in 1922, Finzi and his mother settled in a rural atmosphere at Painswick in Gloucestershire. There he attempted to put his emerging philosophical ideals to practice. Convinced of the superiority of rural life, he eagerly sought the chance to live independently off the land as a vegetarian, and to compose in solitude. Now, after the interruption of the London years, he looked again to the country for a place to settle with his family. First living at Aldbourne in Wiltshire, where their two sons were born, the Finzis eventually acquired a 16-acre site high on the Hampshire hills. By 1939, the home they designed for working practically was completed at Ashmansworth, near Newbury:

It was a house to settle into and work in, easy-to-run, with Finzi's music room, where he could be undisturbed, at the opposite end of the house to the nursery, and his wife's studio, where she could--theoretically--be undisturbed, over the old stables. There was room for Finzi's growing collection of books and rare apple trees and for the other crops a vegetarian enjoyed. (McVeagh, 68) |

Aside from the war years he spent working in London in the Ministry of War Transport, Finzi resided permanently there at Church Farm at Ashmansworth. (Caesar) Finzi's new-found contentment with wife and family enabled him to address many projects with great enthusiasm. Finzi hated the idea of things passing away, and thus he was driven to collect and cultivate, always championing the cause of the neglected. (McVeagh, 594) Whether it was the informal welcoming of stray cats, the salvation of some 400 varieties of apple trees from extinction, or his more academic undertakings, all were pursued with great commitment. (Bliss, 6) (Caesar, x)

Finzi's first encounter with the music of Gurney during his study with Bairstow not only influenced his own composition but also motivated a commitment to Gurney's work and the furthering of his reputation. Finzi was a major force behind the Music and Letters Gurney Symposium of 1938, and the publications of Gurney's works: the first volume of songs in 1937, another song volume in 1952, and a collection of poetry in 1954. Similar efforts in later years followed with the scholarly editing of eighteenth century musical works by William Boyce, John Stanley, Capel Bond, Richard Mudge, and others. (Caesar, viii)

Finzi was never proficient on any instrument. His founding of the Newbury String Players, a small, mainly amateur orchestra, toward the beginning of World War II provided him with his first experience performing music publicly and proficiently. Although by nature one who dislike public appearances, Finzi was to find his experiences as conductor of the group to be a vital feature in his own musicianship, as well as in his personal campaign for the underdogs, as it were. Following Finzi's intent, the group explored chamber music by little-known composers of the past, including those who benefited from his previously mentioned editorial efforts. First performances were also given to new music by unsung young composers. To many of these, he offered assistance or consultation as private students of composition. (Vogel, 9)

Following World War II, Finzi received the first of several commissions for his compositional efforts, including such choral works as Lo, the Full, the Final Sacrifice and For St. Cecilia. (C. Finzi) Other choral works, such as the ambitious Intimations of Immortality, brought recognition with their performances at the Three Choirs Festival. His confidence and experience were evident in the larger works for orchestra which he completed during this time, two concertos 9clarinet and cello) and the Grand Fantasia and Toccata for piano and orchestra. (McVeagh, 69) Two solo song sets found their completion dates within this period as well: Let Us Garlands Bring and Before and After Summer. (Banfield, 446) Yet as always, there is no easy chronological dating of any of these works. Finzi was a slow worker, often taking several years to complete a single movement or song. (C. Finzi) Their listing here is largely indicative of their having been put together in final form for publication at that time.

In the final stage of his life, Finzi was, as he always had been, preoccupied with time, or the lack of it. He was haunted by the sense that he would never have time to complete all that was in him to write. This was apparent long before, reaching back to his childhood when he was forced to deal with the deaths of so many before their time. At age 26, his own brief stay in a sanatorium for tuberculosis no doubt added to this haunted sense. (Ferguson, 134) He had set the Milton texts at that time, and he quoted a portion again in 1941, when his work was interrupted by war:

When I consider how my light is spent Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide, And that one Talent which is death to hide, Lodged with me useless . . . (Banfield, 277) |

When in 1951, he was diagnosed as having a form of leukemia and was given only 10 years to live, his fears were realized. He quoted the poet Tychborne in the "Preface" to his own catalog of works, soon after his knowledge of the diagnosis: "At 49 I feel I have hardly begun my work, 'My thread is cut, and yet it is not spun;/And now I live, and now my life is done.' " (Vogel, 10) Even with the knowledge of his declining health, Finzi was apparently unrebellious. He continued with his quiet, conscientious composition in rural seclusion until his death. (Banfield, 275) The disease had greatly weakened his immune system, and he died of shingles on September 26, 1956, from a chance contact with the chickenpox virus during the Gloucester Festival of that same year. (McVeagh)

From: Samuel Rudolph Germany's dissertation entitled: The Solo Vocal Collections of Gerald R. Finzi Suitable for Performance by the High Male Voice. Dr. Germany extended permission to post this excerpt on December 20th, 2010.

Previous scholarly studies, in their attempts to explain his long-standing connection with Thomas Hardy, have shed much light on the personality of Gerald Finzi. McVeagh quotes Finzi's own explanation of this connection, in which Finzi singles out a sentence from Rudland's Life of Hardy:

I have always loved him [Hardy] so much and from earliest days responded, not so much to an influence, as to a kinship with him. (I don't mean kinship with his genius, alas, but with his mental make-up.) "The first manifest characteristic of the man . . is his detestation of all the useless suffering that fills the world; and the thought that it is unnecessary is to him a nightmare." (McVeagh) |

In childhood, Finzi had witnessed his own share of suffering, much of it connected with war and premature death. Thus, his own feeling of the futility of war intermingled with his fundamental misgivings about life. (Banfield, 276) T. Hold recognizes, however, that in his music, Finzi captured the melancholy of such feelings without the bitterness. (Hold, 310) Perhaps this was also true in his life.

Finzi was an agnostic, possessing in his character a mixture of stoicism and fatalism. Like Hardy, he held to the force of chance in life. (McVeagh) But whereas Hardy's rejection of Christianity was bitter and rigid, Banfield comments on Finzi's more mellow temperament even in such matters as these: "Personally unable to accept the Christian myth, he was nevertheless capable of wishing that its truth might be regenerated for him." (Banfield, 275) Christopher Finzi notes that his father's position on such matters was neither vehement nor hesitant. It was simply a matter of fact. (C. Finzi)

Finzi's personality was encircled by a vibrancy and an abundance of energy. He certainly could be quite defiant on issues when he felt such a reaction was needed. yet within the man was a strong sense of nostalgia, in which the past was, in some ways, more intense than the present. (C. Finzi) He treasured the "power of the memory to crystallize the past." (McVeagh) And it is increasingly apparent that a sense of melancholy was definitely present within his complex makeup of intellect and emotion. Finzi stated that "the proportion of feeling, combined with intellect, must, of course vary with the individual." (G. Finzi, 14) In Finzi, the scales tipped more toward feeling than reason. (Banfield, 276) It was the ability to respond freely that was most essential to him. (C. Finzi) He valued it in others, referring to it as the heightened perception with which all response is intensely felt:

| If this form of heightened perception is possessed by a few throughout their lives, and is experienced at certain heightened moments by almost everyone, to the more sustained artist who possesses the "endorsement from a centre of disciplined experience" it is a constant inner flame, a part of his make-up, a reservoir of feeling on which he can call at anytime. . . (G. Finzi, 9) |

From: Samuel Rudolph Germany's dissertation entitled: The Solo Vocal Collections of Gerald R. Finzi Suitable for Performance by the High Male Voice. Dr. Germany extended permission to post this excerpt on December 20th, 2010.

The early roots of English vocal music were rich with sensitivity to the English language. Purcell and his predecessors knew how the English language responded to music, and how music responded to the English language. But in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, English song composers largely attempted to follow foreign examples in song settings. Henry Raynor states that such an approach either the poetry that grows immediately out of colloquial speech or that which intensifies the idiosyncrasies of the language." (Raynor, 66) During that time the English language was largely considered to be inappropriate for music. As a result, stilted, metrical settings of songs prevailed, and England, until about 1880, lacked a musical response to almost the entire Romantic movement with its wealth of subjective response to language in song. (Banfield, 12)

Gerald Finzi is recognized as one of a large group of English song composers of the early twentieth century who adopted the texts of Romanticism and assimilated the methods of musical Romanticism to bring, as it were, "the deadened imagination out of hibernation." (Banfield, 12) Stephen Banfield relates, in Finzi's own terminology, the crucial need that had existed for a compulsive "chosen identification," the need to express something individual and personal in the composer's own imagination by comparing it with the poet's:

A start could only be made by the careful nurturing of a response which had not been forced upon the composer's sensibilities from some alien source but which was innate and could be personal, different for each individual: a response to literature, the only secure lifeline to the sources of English Romanticism. Thereby the composer could develop his "chosen identification." (Banfield, 12) |

Finzi often stressed that an individual response to words constitutes the most significant factor in composing songs and that native song emerges from native language. (G. Finzi, 3) His own chosen identification was with his beloved English literature and resulted in a compellingly realistic presentation of the sounds of the English language in music. His receptiveness to poetry's variable nuances made Finzi on of the finest composers of English song in this or any era. (Walker, 8) He created melodic lines whose rhythmic complexity accepted prolongations, hesitations and minute varieties of stress as fundamental. Although his word setting can be seen as directly in line with the work of Vaughan Williams, Moeran, Ireland, Warlock, and Gurney, (Raynor, 70) none truly predated him in this ability or to this degree. (Ferguson)

Finzi's subjective expression of the text through accompaniment and harmony follows in the essentially Romantic tradition, creating a culminating rather than an innovative effect. (Banfield, 324) This conservative, backward-looking element gives evidence not only of the musical influences which are present in his work but also of those which are notably absent. Vaughan Williams, Elgar, and Parry are readily identifiable as native contributors to the Finzi style. The noticeable foreign influence is that of Bach, whose Baroque contrapuntal characteristics are clearly more apparent than those from any intervening periods. (McVeagh, 595) Conspicuously absent are the contemporary influences of the Parisian neo-classicists and the Viennese serialists. (McCoy, 8) Bliss states that Finzi "owed nothing to Schoenberg, Hindemith, Bartok, and Stravinsky. . . Well versed in the musical and literary traditions of England, he expressed love for their traditions alone." (Bliss, 6) Boyd comments that "Gerald Finzi is a quiet composer, whose music breaths the air of the countryside by which he is surrounded." (Boyd, 18)

In fact, at St. James Church in Ashmansworth, adjacent to the Finzi's Church Farm, an engraved window by Laurence Whistler was dedicated to the memory of Gerald Finzi. (Butt, 581) The window depicts music as a symbolic tree, its roots ending, or rather beginning, with the initials of fifty English composers, and its branches budding into notes. The English countryside is shown surrounding the tree. Framing the scene are four famous lines of English literature in praise of music. It is entitled "In Celebration of English Music" and aptly portrays Finzi's place in history as a truly English composer, one known most for his vocal music and one whose work is absorbed by the expression of his native English language and literature. (Window)

Yet it was more than just the fires of nationalism at work, for Finzi's harmonic isolation from the surge of tonal experimentation was even more severe than that of many of his own English contemporaries. (McCoy, 9) For this element, he was frequently criticized, especially in the earlier years. Finzi's view of art does not demand originality in concepts. He does not strive to grasp the new or the unexpressed. Banfield quotes Barton: "As has been said of Hardy, 'As an artist, he prefers an old world, whose accumulated tragedies he can count as part of his own experience.' " (Banfield, 279) But increasingly, as Finzi's work has gained repute, rebuttals of such negative views show his conservatism in a positive light. Russell evaluates Finzi's work as "unremitting exaltation . . . of integrity over novelty." (Russell, 9) "His style is so different from those of his much-noised contemporaries that he is regarded as a placid backwater off the main stream, as one who (it would seem) almost perversely writes music which is a joy to perform and a pleasure to listen to." (Russell, 15) N. G. Long states: "The point is that Finzi writes sensitive and fastidious music, and it should be judged and enjoyed on its merits, and not prejudged according to whether or not it follows some hypothetical stream of music." (Long, 7)

In summarizing Finzi's historical role, Stephen Banfield writes:

Standing off from some of Finzi's greatest songs . . . one perceives in them an uncanny sense of the eschatological. The poet's preoccupation with love and its ultimate cessation and the composer's assimilation of the old, dry, unadorned bare bones of three or four centuries of dominant-based western tonality are fused together in lyrical statements about love and death, time, tradition and destiny. Bearing the weight of the Romantic experience in this musical language as Hardy does in the philosophy, Finzi stands at the end of a lyrical tradition, a tradition stretching back beyond Schubert to figures such as Lawes and Pelham Humfrey. While Britten was still to build on parts of that tradition, there sere vital aspects of its codification of deep, timeless emotions through the expressiveness of tonality that Finzi was perhaps the last composer fully to understand. (Banfield, 299) |

Certainly Finzi possessed a clear understanding of his own place in the historical scheme of things. Ina series of lectures presented at the Royal College of Music entitled "The Composer's Use of Words" he articulated a knowledgeable, and on occasion provocative view of the history and aesthetics of the English song. (McVeagh, 595) Although Finzi's comments that follow were not intended as a defense of his own position as a composer of the twentieth century writing in an essentially nineteenth century idiom, perhaps they could serve such a purpose more than adequately:

Not all things can be bad simply because they are succeeded by something else. . . We must therefore be careful not to confuse idiom with individuality and we must realize that composers may still be significant even though their language is one which, for the time being, is not in current use. Throughout musical history we find the same confusion of idiom with individuality. We condemn a school because the language has become familiar or distant, jaded, or incomprehensible to us, and it needs a rare critical judgement to realize that greatness remains greatness whatever idiom it uses. Whether such examples from the past help us to have sounder judgements today depends upon how much we realize that men are great or small not according to their language but according to their stature. (G. Finzi, 8) |

STYLISTIC TRAITS OF FINZI'S VOCAL MUSIC

From: Samuel Rudolph Germany's dissertation entitled: The Solo Vocal Collections of Gerald R. Finzi Suitable for Performance by the High Male Voice. Dr. Germany extended permission to post this excerpt on December 20th, 2010.

General Output

Gerald Finzi's musical output contains three large orchestral works in the genre of the concerto with solo works for piano, cello, and clarinet. He also wrote several instrumental chamber works. (McVeagh) However, the bulk of his output, and that which has received the most critical acclaim, is made up of vocal compositions. Both choral compost ions and solo songs were his major venues. He is acknowledged essentially as a miniaturist in his greatest compositional achievements, the solo songs. Finzi completed 90 solo songs, 71 of which comprise thirteen song collections. This figure, no doubt, would have been larger, had he finished the over 60 song fragments that remained incomplete upon his unfortunate early death. (Banfield, 444-7) (See Appendix A.)

Stylistic Traits

An immense and deep perception of English literature and poetry, unusually well-developed at an early age, formed the foundation and springboard for much of Finzi's creativity. (Burn) His son, Christopher, states: "He was probably a literary man first and a musician second, in one sense. I think there was no other musician who read as widely in the English language as he did, or had such an extensive knowledge of English literature." (C. Finzi) In everyday talk and letters, Finzi quoted from the great English writers because they were his chosen everyday companions. (McVeagh) Finzi's own outstanding library of over 3,000 volumes contained English literature of every period, revealing a breadth of interest and devotion to both major and minor authors. (Caesar, ix-x) Among those who provided inspiration for his music were Thomas Hardy, John Milton, Robert Bridges, Edmund Blunden, Thomas Traherne, William Wordsworth, and William Shakespeare. (Banfield, 444-6) In the selection of texts to be set to music, Finzi chose only those with which he felt a strong kinship. General textual topics which support his own philosophies of life recur in his settings. Among these topics are those that reveal a preoccupation with the passing of time, a sense of fatalism, and the power of the memory to hold moments of the past. Also reappearing are those dealing with the futility of war and the beauty of nature. Finzi was additionally drawn to the innocence of youth and child hood. (Banfield, 276-8)

In selecting these texts with which he felt such strong kinship, Finzi often chose poetry which some considered unsettable. Finzi acknowledged technical reasons for difficulty with certain texts:

Often unsingable sounds dominate (too many consonants, or poor placement of vowels on which to sing), or poems were too tightly packed with intellectual concepts to allow a successful setting. The composer risks finding problematic areas in any group of words, but should not be deterred by difficulties if one identifies with the words, and intuition strongly bears out the musical impulse to set the words. (Finzi, 5) |

Finzi ardently disagreed with critics who recommended that musicians should avoid distorting great or even good poetry by coupling it with music. (Cline, 13) He wrote:

I do hate the bilge and bunkum about composers trying to "add" to a poem; that a fine poem is complete in itself, and to set it is only to gild the lily, and so on. It's the sort of cliche which goes on being repeated (rather like the phrase "but art is above national boundaries"). I rather expected it [over the setting of the two Milton Sonnets] and expect it still more when the Intimations [of Immortality] is finished. But alas, composers can't rush into print, particularly where their own works are concerned --- (though I do sometimes have a sneaking wish that editors would ask for one's opinion!). Obviously a poem may be unsatisfactory in itself for setting, but that is a purely musical consideration -- that it has no architectural possibilities; no broad vowels where climaxes should be, and so on. But the first and last thing is that a composer is (presumably) moved by a poem and wishes to identify himself with it and share it. Whether he is moved by a good or a bad poem is beside the question. John [Herbert Sumsion] hit the nail on the head the other day when we were going through a dreadful biblical cantata, which x had sent him. . . John said, "He chose his text, it didn't choose him." I don't think everyone realizes the difference between choosing a text and being chosen by one. (Ferguson, 131) |

Diana McVeagh illustrates the initial stage of Finzi's unusual compositional process and the manner in which the literature so inspired him: "As lines [of poetry] ran through his head, so they would gather music to them." (McVeagh) "He would read something and it would produce maybe only a couple of bars . . . a completely spontaneous reaction. he might then find that was all he got, and he would put it away in his drawer and leave it." (C. Finzi) He would not necessarily start with the first line, but with any phrase that suggested music. Only rarely were revisions made to these first incomplete sketches. (Banfield, 287) Works would then continue in process, each added to from time to time until a large batch of sketches, generally quite discontinuous, was compiled for a particular work. (Ferguson, 131)

Finzi often spread the composition of a single work out over a number of years until he began the completing stage. This putting-together of the sketches by filling in the gaps was never an entirely fluent endeavor; songs that appeared spontaneous might have been compiled only after endless sketches and rough drafts. (Ferguson, 131) Finzi hated intellectually contrived solutions. Yet his favorite phrase, "art conceals art," (C. Finzi) reveals the balance he sought:

The emotional response . . . was evidently innate in him and the more intellectual response . . . he had to kind of force upon himself. In such a manner, he was trying, I guess, to arrange so that a technical solution would not appear technical. It is apparent that he was generally successful at that. You'd think that would be absolutely impossible, but it never sounds like a patchwork quilt. (Ferguson) |

Due to his compositional process, unfinished works from many early years abound. Over 60 song fragments remained unfinished upon his death although a gratifying number of early fragments were completed in his final, comparatively prolific year. (Banfield, 287) Finzi assigned opus numbers when he began works rather than when he completed them. Thus blank opus numbers have resulted from works which were planned but not finished. In addition, the posthumous works have earlier opus numbers than those of the last works published in his lifetime. (Ferguson, 132)

Lack Of Chronological Development

Other features are recognizable as being directly linked to Finzi's idiosyncratic compositional process. Amazingly, stylistic disunity is never noted in collections whose individual pieces were composed over a long period. This is due to what some refer to as a homogeneous style, which permeates all Finzi's music. Apart from the very early writings, Finzi's work shows very little chronological development. This has been a controversial issue among critics seeking to evaluate his work. (C. Finzi)

Finzi's conservative harmonic language is definitely tonal. Tonic and dominant scale-degrees still possess a traditional, mutually polarizing, function. (Banfield, 284) Often these degrees are used obsessively in a characteristic inverted pedal point. Banfield refers to these as restless, searching tonic and dominants which subjectively depict textual mood. (Banfield, 324)

Evaluators note that most of Finzi's specific harmonic traits are tools of subjective mood setting. N. G. Long recognizes a prevailing type of harmony with many seventh chords, other extended harmonies, and suspensions as correlating with the brooding or fatalistic substance of many poems which Finzi chose to set. (Long, 9) In contrast, exclusive use of triadic harmonies is quite rare. (Hansler, 403) Finzi's rich, nostalgic harmony, then, employs chromaticisms of the nonharmonic tone type to convey the mood of the text. (Parker, 18) This results in a rich harmonic effect, spiced with the bittersweet dissonances which resolve, only to be replaced by new ones in other lines. (Hansler, 403)

Finzi employs other chromaticisms temporarily to blur or suspend the tonality and to achieve color by segments of modality in the manner of Ralph Vaughan williams. (Cline, 32) Even though the tonality is clear, Finzi often uses tonic avoidance at cadences to achieve continuation of poetic thought. (Parker, 18) Occasionally, he uses other practices to obscure the tonality in varying degrees: the employment of the tonic only in weak inversions or on weak beats after a new key is suggested by accidentals; and the suggestion of two closely related keys, often a major and its relative minor, without clearly establishing either one. (Hansler, 398)

Finzi does not use harmony as a structural device. (Ferguson) He almost totally avoids fully harmonized modulations to the dominant and subdominant keys. Frequently he begins and ends a song in different keys, with no apparent sense of pattern. This is not seen as a freeing influence of the twentieth century upon his work. Whether this is a chosen abhorrence of intellectually contrived solutions (C. Finzi) or something which simply is not inherent to his nature, (Ferguson) perhaps it is connected to his fragmented compositional process. (Ferguson)

Finzi produces some of the most singable melodies in the English repertoire of the twentieth century, a feature that is remarkable for a non-singer. (Ferguson) Banfield compares this singable quality to that of a folk tune:

However much he disguises the simplicity of his vocal lines by irregularising the phrase-lengths and elasticating the rhythms to the mould of speech-stresses, one is nearly always aware of the fundamental plan of a neatly and simply phrased tune that needs no accompaniment to give it structural balance. (Banfield, 280) |

This fluency with creating vocal lines also affects his instrumental writing. Few contemporary composers, in the lyrical aspect, wrote so vocally in every way. "the voice was his starting point." (C. Finzi)

As the vocal melody is his initial inspiration for the rest of the musical composition, so the sound and meaning of the text provide the initial impulse for the melody. Finzi comments to Edmund Blunden: "I like music to grow out of the actual words and not be fitted to them." (Burn) Walker observes that Finzi allows the poetry to shape his musical thought: "He never imposes himself upon the words but rather allows himself to be imposed upon by them." (Walker, 8) His resolution of text into musical solutions is not a technical thing; it is spontaneous, in keeping with his general compositional process. (C. Finzi)

The melodic contour of the vocal line is never virtuosic or obtrusive, and this quality of "homeliness" is determined by Finzi's speech-like word settings. The shapes of his melodies often follow the rise and fall of the inflection of the conversational or reciting voice. This has the effect of making Finzi's vocal lines quite unforced, natural, and often emotionally low-pitched and conversational. (Banfield, 282) In settings, Finzi aptly uses a mixture of lyrical arioso and recitative. (Boyd, 21)

Rhythmically, the vocal lines of Finzi's songs are obvious conversational matches to the poetry. (Banfield, 325) In some settings, on the surface, Finzi's rhythms can appear to be highly complex and difficult, yet upon reading the text they make sense. Finzi emphasizes that "the natural rhythm and stress of words must be preserved at the expense of metrical accents." (G. Finzi, 10) However, he sometimes uses metric manipulation of irregular with regular meters for proper transcription of syllabic emphasis. (Cline, 34) When setting poetry with lines of equal length and more recognizable rhyme schemes, Finzi exhibits more regularity and repetition. (Parker, 14) The overall rhythmic freedom of the vocal line within the framework of a more tightly constructed instrumental accompaniment is crucial to the effectiveness of much of Finzi's vocal writing. (Long, 9)

Finzi's songs are almost exclusively syllabic. (Banfield, 325) In his lectures, "The Composer's Use of Words," Finzi does not express opposition to melismatic settings, but he recognizes that such a style places words in a somewhat secondary role. (G. Finzi, 2) He writes: "Melisma . . . can become the handmaid of a melodic line and enhance it in a way that syllabic treatment could never do, even though it may be, in a slight way, at the expense of the words." (G. Finzi, 5) However, his feelings regarding virtuosic exhibition in song are clearly stated:

It is no condemnation of virtuosity to say that in any age where the cadenza becomes more important than the song, where the audience goes to be thrilled by the purely physical at the expense of content, the composer for whom words have any significance, must find himself in a vacuum. (G. Finzi, 3) |

He also did not exalt the extreme of merely heightened speech:

At their extremes both [melismatic and strictly syllabic settings] court disaster, the disaster of meretriciousness, of superficial soap-bubble emptiness at the one end and of pedantry and un-creativeness at the other, whilst [sic] a fusion of the two, in varying expression in any age. (G. Finzi, 2) |

With his prevalent syllabic style, Finzi's own position on the continuum indeed can be seen as ruled more by the words and his respect for their recognition. Perhaps Finzi felt a close affinity with the French songwriters, whose common use of syllabic settings he correlated with an intense respect for their language. (G. Finzi, 5)

Banfield refers to the severely syllabic style as "the circumscribed invention of the vocal content," (Banfield, 325) and criticizes it as a limitation as most evident in Finzi:

In English song, from Parry onwards, one must . . . consider the almost ethical aversion to melismatic or virtuoso vocal writing, and the adherence to the more than ethical Anglican tradition of "for every syllable a note." "Just declamation," at its severest in Finzi, became an inhibition which needed to be broken down . . . [in order to achieve greater freedom and expression to the vocal line]. (Banfield, 325) |

Finzi, however, recognizes more florid settings, as exemplified by Benjamin Britten, as an acceptable, alternative style to that in which words are the first consideration. (G. Finzi, 7) He states that "neither view is better than the other; their value is in their difference; neither are new conceptions and both styles will inevitably flower again and again, one after the other, for the continual refreshment of the spirit." (G. Finzi, 8)

Donald Ivey credits Finzi, along with Warlock, with the establishment of a more linear texture in English song writing with greater contrapuntal interest between accompaniment and vocal line. (Ivey, 239) Finzi's affinity for contrapuntal writing is quite evident early on, and the imitative aspect, even when it is not strict counterpoint, stays very strong throughout his life. Finzi's writings indicate preference for the free or partially free type of imitation. (Hansler, 397) Interludes and underpinnings in the accompaniments are riddled with imitative entrances based on motives from the melodic line. Motivic ideas, much more than harmonic ideas, control forward movement, (Cline, 32) often resulting in what is considered to be rather weak harmonic progression. (Banfield, 280)

The essentially vocal inspiration gives Finzi's accompaniments certain other limitations. The first of these, an excessive continuity, contributes to one of the cliches of Finzi's work. The steady pulsing bass line, and other such ostinato patterns in accompaniments not unlike Elgar and Vaughan Williams, are characteristic of many songs. (Long, 9) A second limitation is apparent in Finzi's piano accompaniments. In the early years, they were not really piano writing at all. They were just contrapuntal lines. (Ferguson) Finzi was not a pianist, and even though it was his chosen instrument for composition, he could not play his own accompaniments. (C. Finzi) Only in the later years did Finzi develop a feeling for writing for the piano, especially notable in all the late songs. Howard Ferguson states that although these late works are not pianistic in the normal sense, they do sound admirable on the piano in a completely individual way. (Ferguson)

It is difficult to define a consistent architectural basis for Finzi's songs, for he rarely duplicates a form. The loosely through-composed variety is among the most effective because Finzi can thus seize all the dramatic possibilities of the poem. (Boyd, 21) Longer songs tend to avoid sectional repetition and become "arioso scenas" whose segments are differentiated by varying rates of movement and figurations, which may or may not possess cross-references between them. (Banfield, 287) Straightforward strophic form is most uncommon; Finzi rarely uses wholesale strophic repetition, preferring to group stanzas into some other perceptible patterns. Most dual-stanza poems are composed to sound like "a single musical paragraph with a caesura in the middle." (Banfield, 287)

Melancholy Influence

Ferguson has commented on the private side of Finzi which revealed a certain melancholy and which affected his composition greatly. His earlier works were almost always slow and lyrical. Slow movements and songs of larger works were invariably the first to be composed. Ferguson states that this was the characteristic mood of his music. (Ferguson, 132) An example of this can be seen in the completed single songs of the late 1920's which came to be parts of later published sets: Dies Natalis, Farewell to Arms, and Two Sonnet by John Milton. The majority of these were slow, lyrical songs, (Banfield, 444-5) "but, as he himself said, a composer grows not only be developing his natural bent, but by reacting against [it]; so it need not surprise us if his mastery of a more vigorous, extrovert type of music was a later manifestation." (Ferguson, 132) Faster music was much harder for him to write in the early years; however, this apparently was one technical weakness which he overcame by the later years. (Ferguson)

From: Samuel Rudolph Germany's dissertation entitled: The Solo Vocal Collections of Gerald R. Finzi Suitable for Performance by the High Male Voice. Dr. Germany extended permission to post this excerpt on December 20th, 2010.

"Cyclic" (Collective) Publication/Performance

Finzi's preparation of completed songs into collections for publication was a task involving much thought and immense care. Only one of the collections can actually be viewed as a cycle, and Finzi did not wish his Hardy settings on the whole to be viewed as cycles. Nonetheless, all songs were published in sets. Although it is doubtful that he created songs with cycles or sets in mind, he would have viewed the finished collections as complete volumes. (C. Finzi) Finzi claimed that in grouping the songs for publication, he was lessening the chances of a single song being overlooked or not being performed. (Banfield, 290) Joy Finzi noted Gerald's emphatic thoughts about the collective nature of his work. The ordering of songs within a set was intended to provide significant contrast for cyclic performance. (Vogel, 5)

Diction Considerations

Finzi's son, Christopher, and Ferguson both agree that a major consideration for singing the songs of Finzi is the articulation of the language. Christopher states that many singers, especially those with big voices, have difficulty singing English well. (C. Finzi) In addition to a lyric voice, Ferguson states that special notice of the consonants is necessary in order to achieve proper articulation of the diction. (Ferguson) Finzi himself stated that "to the composer for whom words are significant (for they are not significant to all composers) the surest way to communicate with his audience is for them to be able to hear and understand the words he is sharing with them." (G. Finzi, 4)

Interpretative Indications

In his detailed approach to language setting, Finzi made frequent use of grace notes. Rhythmically, they should always appear before the note. (Ferguson) Unfortunately, other details of the musical score are not always as clear. Ferguson, a frequent interpreter of Finzi's music in performance, noted that in the early years, Finzi exhibited a great deal of uncertainty in matters of detail for the performer:

He tended to solve the difficulty by leaving out such indications altogether, until it was pointed out to him that this did not make the life of the performer any easier. He would then agree, rather reluctantly, to a piano here and a forte there, and an occasional slur to show the beginning and end of a phrase, adding under his breath that the performer, if he were any sort of musician would instinctively do it like that anyway. (Ferguson, 133) |

Due to his lack of performance experience, Finzi had little confidence in such matters. These problems, however, began to diminish with his conducting the Newbury String Players. It was really with them that he first learned the point of view of a performer, which he had ridiculed before. As a result of these experiences, his attention to interpretative indications became more detailed. (Ferguson)

Even with this increase in direction, Finzi was still less specific than some other composers. This was due, largely, to his never performing as a soloist and to his lack of proficiency on any instrument. Thus, even with his increased experience via conducting, he was unaware of all the specifics a performer would want to know. (Ferguson) Furthermore, as a profoundly shy man, he was far too embarrassed to provide a good interpretation of his own music for performance. (C. Finzi)

Finzi always looked to the performer for appropriateness in good interpretation of his work, and there was flexibility in his thought process for that. Finzi realized that no amount of markings could guarantee a good performance. He was comfortable with the idea of different interpretations of his compositions. Dangers do exist, however, among the less than ideal situations of performance. Christopher Finzi, who has conducted many of his father's works, notes a tendency among performers to overdo the direction Finzi did give. (C. Finzi) Ferguson remarks that, regarding dynamic indication, sometimes too little and sometimes too much was given; overall, it would be better just for the singer to react. (Ferguson)

Ferguson gives important remarks concerning the appropriate interpretation of Finzi's accompaniments. As one of Finzi's oldest and closest friends, he was often involved in the making of a Finzi work. He knew Finzi's musical mind as well as anyone. Ferguson was the pianist in several premiere performances, as well as on recordings. (McVeagh, 19) His remarks indicate that rubato, especially at the marginal level, is an essential feature of Finzi's music which cannot accurately be indicated and which is vital to the accompaniment. Furthermore, it is this feature which makes Finzi's music difficult for some to interpret at the piano. "It's rather rare to encounter somebody who naturally feels how Gerald's music should go. It's partly a give and take rhythmically and a live line instead of something that's strict." Ferguson was influential in the selection of Clifford Benson as pianist for several recent recordings of Finzi's works, noting that Benson has a remarkable natural feel for Finzi's piano accompaniments. (Ferguson)

Ferguson enumerates other elements which are essential to an appropriate interpretation of Finzi's piano accompaniments. It is obvious that in Finzi's music there is never a conception of a vocal line and a foundation upon which it is set. Instead, the pianist must recognize the equal partnership which exists between voice and piano there are many times that the accompaniment seems to be singing exactly what was just sung by the voice. The contrapuntal nature of the piano writing supports what should be incorporated in any accompaniment. "You have to mentally orchestrate it, so that it's in different layers of sound, rather than something flat that you just throw at the wall." (Ferguson)

Commentators have noted general inclinations in Finzi's voice designations for his solo works. Joy Finzi spoke of Finzi's affinity for middle-ranged instruments and voices. (Cline, 25) It has been noted that this affinity included male solo voices. In the last year of Finzi's life, Joy reported on a compositional effort: "Hoping it was going to be a tenor song it turned, in the final making, into an inevitable baritone." (Banfield, 299) Previously documented research efforts have already supported this fondness for the baritone. (Cline & Vogel)

It has been recognized that Finzi had a marked preference for the male solo voice in general, (Ferguson & C. Finzi) but perhaps this feature has not been given adequate notice. There is a marked absence of anything written specifying mezzo soprano and no work exclusively for soprano. Only Dies Natalis lists the soprano voice, and then it is an option (soprano or tenor). Of the nine collections compiled by Finzi himself, eight contain specifications for male voice and none contain the generic high/low voice indication. Four of the thirteen solo collections were published posthumously, and only these contain the generic indication. Finzi's possible intentions for these latter works appear in the "Editors' Notes" from the published scores of Oh Fair to See and till Earth Outwears. When explaining the transposition of songs, the editors state that Finzi described uncertainty over whether a given song was suitable for baritone or tenor. Perhaps, had Finzi lived to publish the remaining works himself, his previous practice would have continued with predominant specification of the male voice. (Finzi, Editor's note)

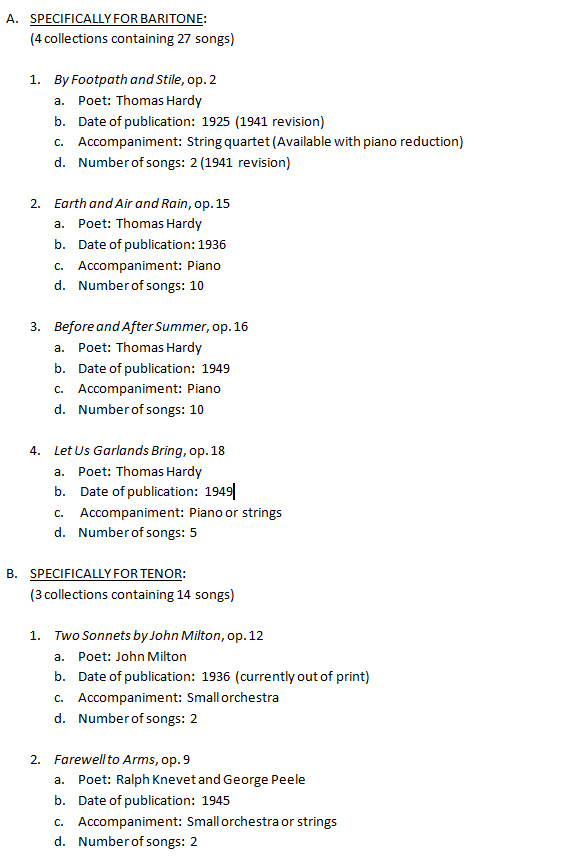

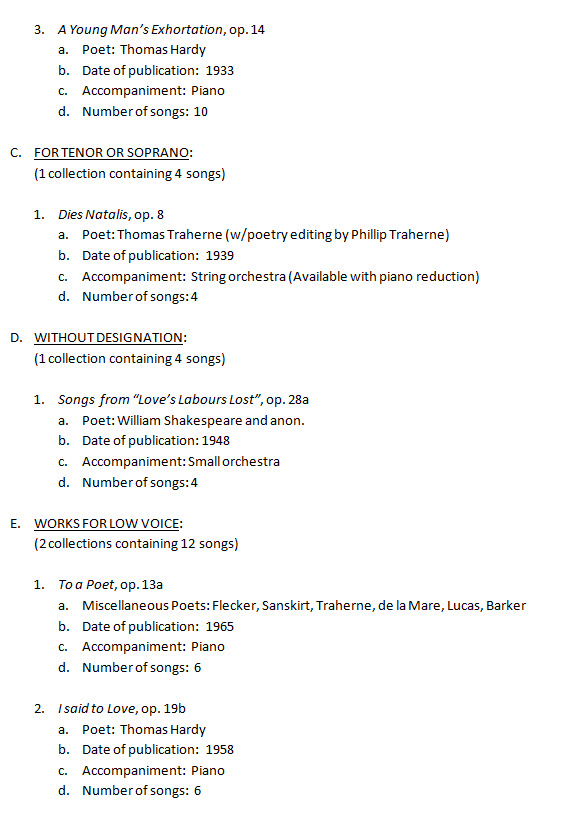

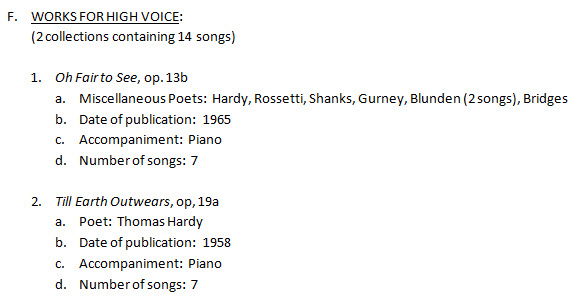

Finzi song lists do show a majority of works written specifically for baritone. However, errors in previous research data possibly have exaggerated this as a greater percentage than it is in actuality. Donald Vogel's research of 1966 contains a listing of Finzi's published compositions by opus number. Vogel includes the solo vocal collections, giving the number of songs in each, but without detailing the individual song titles. (Vogel, 117-9) Banfield's research of 1981 contains a more specific listing of all the individual songs and fragments composed by Finzi, published and unpublished, indicating those compiled to form solo vocal collections. (Banfield, 444-7) (See Appendix A.) Taking into account deleted items from Banfield's list which are irrelevant to this study, (see annotation) both lists contain the same vocal collections, which, in fact, include 71 songs. However, Vogel lists only 63 songs in the body of his document. It is obvious from the way he lists the items in his Appendix that he fails to count Dies Natalis, Farewell to Arms, and Two Sonnets (all with tenor designations) among the total song compositions of Gerald Finzi. These would account for the eight-song difference between his quoted figure of 63 and the actual total of 71 songs which are included in the combined collections. Furthermore, Vogel's introductory statement is not consistent with his own appendix list. He states that 39 songs are designated specifically for the low male voice, whereas, in his own list, only 22 songs are shown as specified for baritone. His miscalculation goes on to list seventeen remaining songs for low voice which could be suitable for the male voice, an error which inaccurately presents the works for baritone as constituting 89% of Finzi's output. (Vogel, 2) According to Banfield, there are 27 songs specified for baritone, with twelve remaining for low voice, giving 39 which could be appropriate for baritone, a possible 54.95 of the complete output. (Banfield, 444-7) (See Appendix B.)

Second highest on the list of songs would be works written specifically for tenor. Fourteen songs were written specifically for tenor, and another four for soprano or tenor. (annotation) Of the remaining fourteen posthumously published works for high voice, many could be considered more appropriate for the male singer due to textual considerations. All of these fourteen could be appropriately performed by tenor. This constitutes a total of 32 songs, from six collections, a possible 45.1% of Finzi's output, which could be performed by the high male voice. (annotation) (See Appendices A. & B.)

Additional data taken from solos in major choral works support this penchant for the male soloist. The high male voice, specifically, is given exclusive, significant solo designation in two of Finzi's most substantial choral works, Intimations of Immortality and For St. Cecilia. (McVeagh, 596)

Finzi respected various specific singers; however, soprano Elsie Suddaby is the only female singer mentioned by commentators. Tenors Eric Greene and Wilfred Brown and baritones John Carol Chase and Robert Irwin were frequently used in performance and recordings of Finzi's works, and Finzi thought well of them. (Ferguson & C. Finzi) With these singers, Finzi's noted preference for the lyric, as opposed to the dramatic, voice type is evident. (Ferguson) Although there were singers whom he did respect, Finzi never wrote anything with a specific singer in mind. His conception of the songs was totally abstract. (C. Finzi)